I wrote this little essay about 25 years ago, when the concept of outsider art was new to the also-new World Wide Web. The real experts hadn’t yet gone online, and something was needed there to explain this kind of art.

Like many of us, I’ve learned a lot since then, and the recent death of Roger Cardinal, whose 1972 book “Outsider Art” originated the term, made me consider revising the essay. It has a bit of history about it, at least for me, though, so I’ve left it as is.

My views about the term have changed, however, especially about the distracting dramatics around its value as a label. The debates over the usefulness and propriety of “outsider art” and similar terms are exhausting — of more interest to academics and critics than to artists and collectors, I suspect. My own conclusion: Everyone is right, and any term anyone comes up with will fail one test or another. Too vague or too specific, too exclusionary or too inclusive, too arcane or too obvious, and so on.

One problem with terms is the complexity of what they purport to describe. Even if one is spot on at the start, over time it will get weighed down with exceptions and edge cases and the fact that the art itself changes, as does the way we view it.

Any term eventually will mean whatever anyone who uses it wants it to mean. That might actually bring more insight to bear, but another person might bring a different, and not entirely consistent, insight. In other hands the term will suffer confusion, indirection and just plain error. Whatever happens, critiques of the original label will become increasingly legitimate over time since most of those people using the term are not doing so with academic precision or sociological sensitivity.

Is anything salvageable from the terminological wreckage? If you believe that behind the labels are some insights about the art, then yes. The key is to ignore the labels and save the insights, to the extent that they accomplish something positive or reveal something meaningful about the character of the art.

In this case, I think “outsider art” starts as a fairly simple idea, even if it doesn’t end that way, even if all kinds of disturbing implications have accreted to make it no longer a proper label for those seeking terms that unambiguously and comfortably fit.

It’s about people making art with no (or minimal) artistic training and with no conventional (or minimal) connection to an art world, which, strictly speaking, is what they are “outside” of. It’s about them solving problems of creativity with their own internal resources rather than what they’ve been trained to do. It doesn’t have to mean — can’t mean — total isolation from all culture, since that would require isolation from the world, period. But it means their artistic engagement with that culture is strictly on their own terms, whatever those terms might be.

Of course, it’s not really all that simple, and things get more complicated very fast. But rather than worrying about the labels, we should worry about the complications themselves. Ultimately, who cares about liking an artist because of what they’re labeled? Use whatever label you, or they, like. Care instead about valuing work by people whose creative efforts would otherwise be ignored because they are not part of an art world, or they lack that conventional connection.

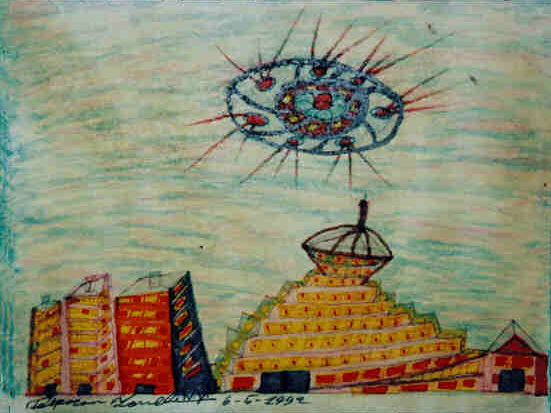

And now, here are some earlier thoughts, circa 1995, with the original images:

What is outsider art?

It’s a question that bedevils collectors and critics, who also worry about related terms such as folk art, self-taught art, vernacular art, naive art and primitive art — words on which there is little consensus about appropriateness or even meaning.

Roughly, though, a working definition of outsider art could go like this:

Creative works– paintings, drawings, sculptures, assemblages, and idiosyncratic gardens and other outdoor constructions — by people who have had little or no formal training in art and who produce (or at least began by producing) art without regard to the mainstream art world’s recognition, marketplace or definitions. These are people who make art for themselves or their immediate community, often without recognizing themselves as artists until some collector or expert comes along to inform that what they are doing is making art.

It is these collectors and experts who have found “outsider art” useful as a way to organize collecting activities and as a marketing term. But the concept implies a certain elitism, since if there is outsider art, there presumably is someone inside designating these others as outside. And what are they outside of? Art schools? Museums? The gallery world? Culture altogether? (That last quality is what some see in the extremes of insane art, the original paradigm for outsider art.)

And there are more questions: What is it about any particular work that makes it outsider, or makes it worthwhile at all? Is there a line between idiosyncrasy, one of the most sought-after qualities in outsider art, and simple incompetence? How outside must someone be to qualify, and what happens when they are discovered by art collectors and dealers and start being influenced by them? Finally, why not call their work just plain art? Why segregate it?

These questions have been debated ad infinitum, and even its defenders admit the concept can be problematic. As a matter of convenience, though, “outsider art” remains widely used. Partly it persists for commercial reasons — demarcating a particular sector of the art market helps to create and sustain it. But it also remains a handy shorthand for work that is liable to reflect different motivations, histories and concerns than that generally produced by art school graduates.

Its visionary quality, putative naivete or innocence, freedom from formal conventions, eccentric use of materials, left-field creativity, wild subject matter or some combination of these qualities are not exclusive to outsider art, of course, but they are to some extent typical of it. In addition, the conditions under which the art is produced do have a meaningful effect on its nature, even if they don’t impart the almost-magical authenticity that some boosters find in outsider art.

For a more authoritative answer to the question “What is outsider art,” go to this Raw Vision page.