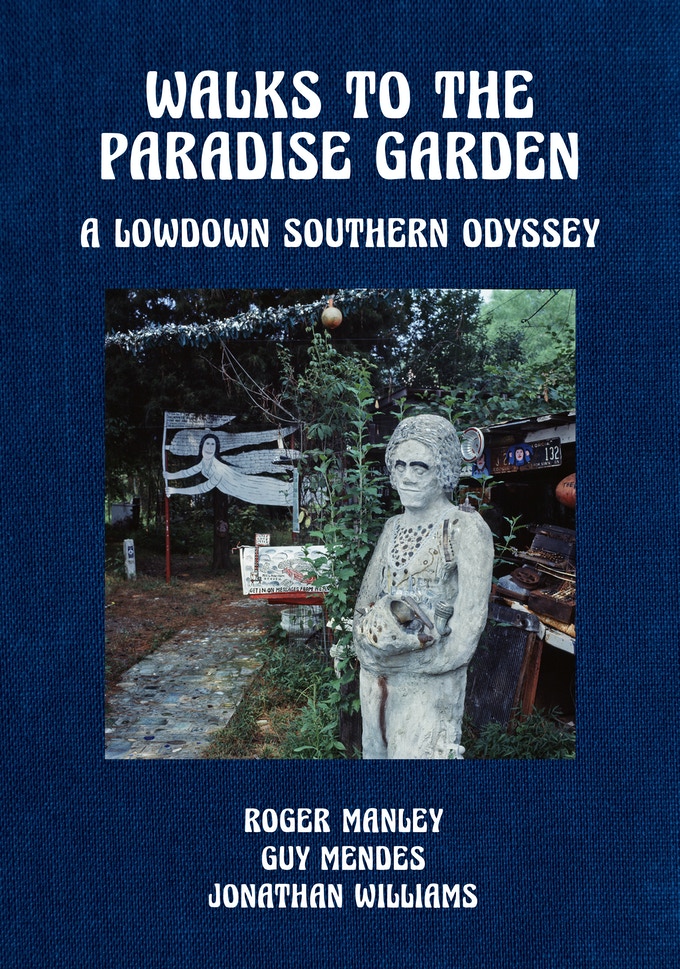

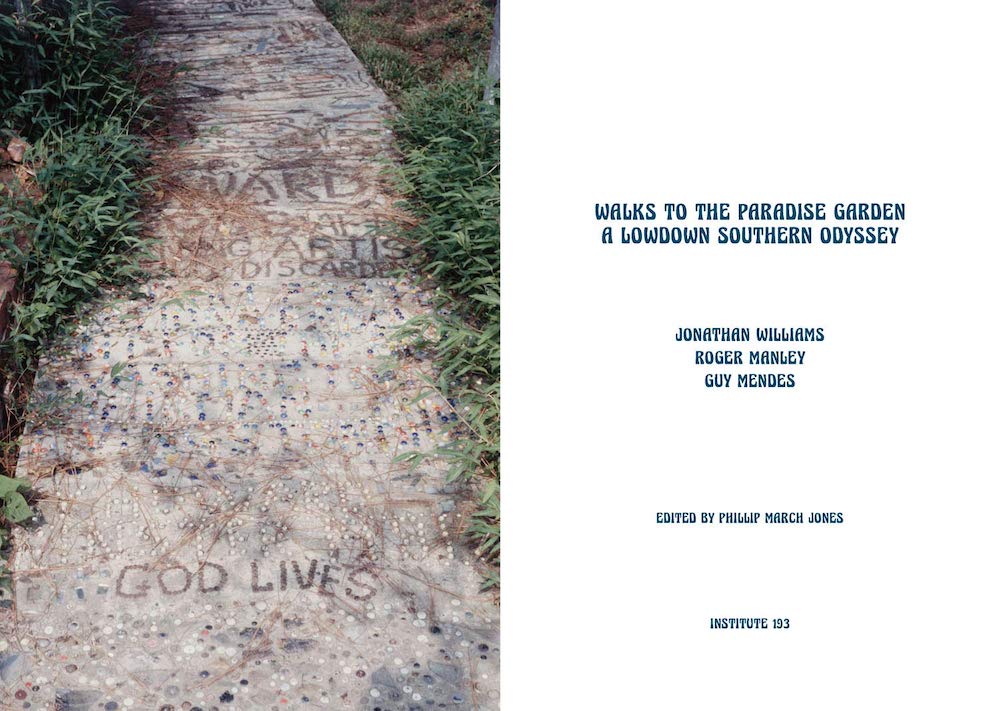

Walks to the Paradise Garden: A Lowdown Southern Odyssey, by Jonathan Williams, photos by Roger Manley & Guy Mendes. Institute 193, Lexington Kentucky and New York, 352 pages, 100 color images and 80 black and white , 2019. ISBN: 978-1732848207. Hardcover, $45.

It’s a shame this book wasn’t published as intended in the 1990s. Not only would its author have still been alive, but so would most of the artists he encountered on his travels across the back roads of the South.

Inspired by William Least Heat-Moon’s Blue Highways, Jonathan Williams, poet, publisher and lover of the vernacular, undertook a series of road trips starting in 1984 and continuing through 1991, a period in which a whole cohort of self-taught southern artists came into their own. For many travelers of that era, Least Heat-Moon’s book-length essay was the authoritative handbook on how to travel well in the United States. Had it been published, Williams’s own volume might have been the authoritative guide to traveling amidst the southern vernacular.

But Williams, who died in 2008, shelved the manuscript for unspecified reasons. Only now has his “wonder book, a guide for a certain kind of imagination,” been resurrected, by Institute 193, an arts organization devoted to “the cultural landscape of the modern South.”

The current editors, besides preparing the manuscript for publication, worked with Williams’s two collaborators and traveling companions, photographers Roger Manley and Guy Mendes, to gather up the many photos they took on those trips. Between their photos and Williams’s narration, even with most of the artists dead and many of the sites the trio documented gone, you can almost feel like you’re there visiting. In that sense, this is a travel book, even if it is unlike any other travel guide you’re likely to have used.

It’s also an art book unlike any other. Refreshingly free of cant and pretense, it is a book more about curiosity, discovery and joy than about art per se, even if it is chock full of it. It is definitely a book about artists or, perhaps, more strictly speaking, creators, since many of its subjects, like so many art brut masters, didn’t consider themselves artists at all, or at least not until somebody told them they were.

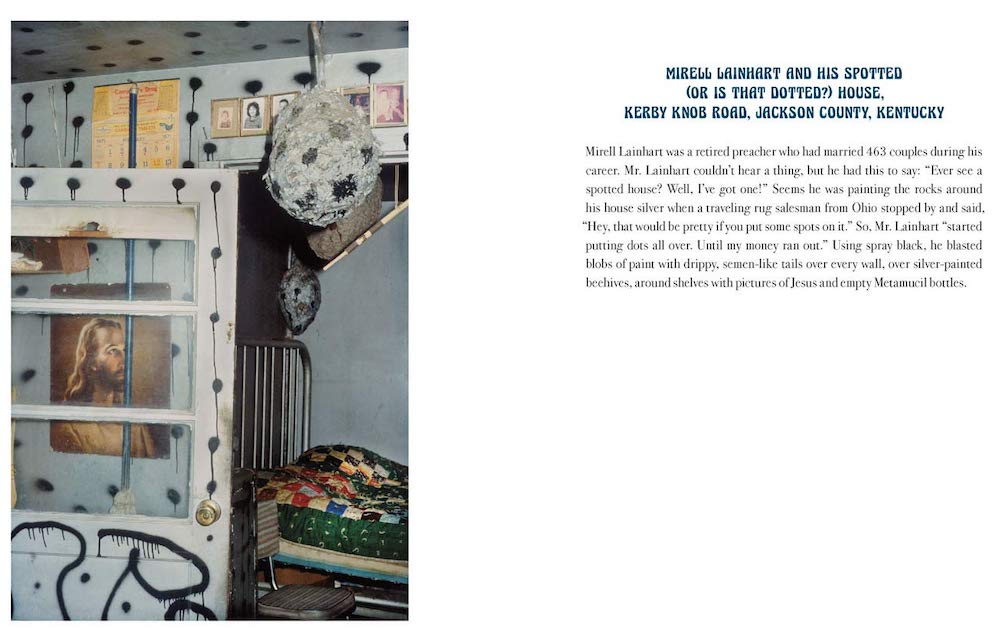

The ever-accessible stalwarts of the 1980s-90s southern folk-art tourism circuit are here—R. A. Miller, Howard Finster, Mose Tolliver and Jim Sudduth, among others. But there are also less commonly known artists and sites, such as the fully dotted house of Mirell Lainhart in Jackson County, Kentucky; James Butt’s Dreamhouse near Moyock, North Carolina, and sculptor Jeff Williams in Sampson County, North Carolina.

In one blockbuster chapter you can find accounts of visits to Mary T. Smith, James Son Ford Thomas, Jim Sudduth, W.C. Rice’s environment, Charlie Lucas, Mose Tolliver and David Butler. Another extended chapter recounts a road trip with the supreme collector of southern black art, William Arnett. Either of these chapters alone are worth the price of admission.

Coming out of the early upsurge of interest in these southern artists, the book is an artifact of its time. It should be read as a first, not last, word on these artists. Its focus on eccentric and entertaining characters can seem anachronistic and occasionally patronizing, though it’s a good bet that Williams considered himself as weird as the people he was writing about. (Then again, perhaps he was projecting his own eccentricity onto people who may not have been quite so odd as he thought.)

He ultimately takes the artists very seriously. You just need to remember that this is pointedly a work of poetry and discovery, not journalism or scholarship. It is a book about personal encounters where quotations seem less the result of interviews than snippets of conversation. The writing can get a bit plummier than typical for art books, but Williams’s story-telling skills keep the narrative from ever going astray.

Even where his appreciation of the art seems like just a glance, his appreciation of the artists runs deep, as seen in encounters with the likes of potter Georgia Blizzard, painter Sam Doyle and the sainted Eddie Owens Martin. These accounts include some choice quotes, like this one, from statue-maker and environment-builder Eldren M. Bailey: “When I was doin’ these things, I didn’t know why I was doin’ ’em. I didn’t know what for. It just broke out on me, kind of like a sore or somethin’, before I knew what I was doin’. Maybe some folks see more in ’em than I see?”

Some of the visits in the book are quite downbeat. Frequently, it’s a matter of an artist’s ill health, but sometimes their ill treatment. Williams relates Mendes’s encounter with David Butler, whose environment in Patterson, Louisiana, was decimated by the enthusiasm of dealers and collectors. “I don’t want you to take my photograph because people will just come and take everything away from me,” Butler told Mendes (who got a photo anyway). Perhaps stories like Butler’s gave Williams pause when it came to publishing a book that would guide still more enthusiasts to these artists and their places.

Another chapter with downbeat moments features Martha Nelson, who essentially invented the Cabbage Patch Kids doll but was outmaneuvered by a partner before they became one of the most popular toys of the 1980s.

For all of Williams’s bravura performance as a chronicler and a poet, the photography that accompanies his text is just as important as the writing, with some of the portraits representing canonical image of their subjects. Manley is well known in the self-taught art field for his activities as a curator, writer, photographer and museum director. Mendes, like Williams, is less prominent in the field but no less attuned to these artists and their work.

The book concludes with a note from the curators of an accompanying exhibit at the High Museum in Atlanta, paying tribute to Manley and Mendez and to other photographers who played important roles in bringing this kind of art to light, including Nathan Lerner and Seymour Rosen. The curators used the photos of Manley and Mendez to great effect in their High exhibit, Way Out There. The large prints were dramatic and, along with selections of work by the pictured artists, created an effective context for appreciating the artists and their documenters.

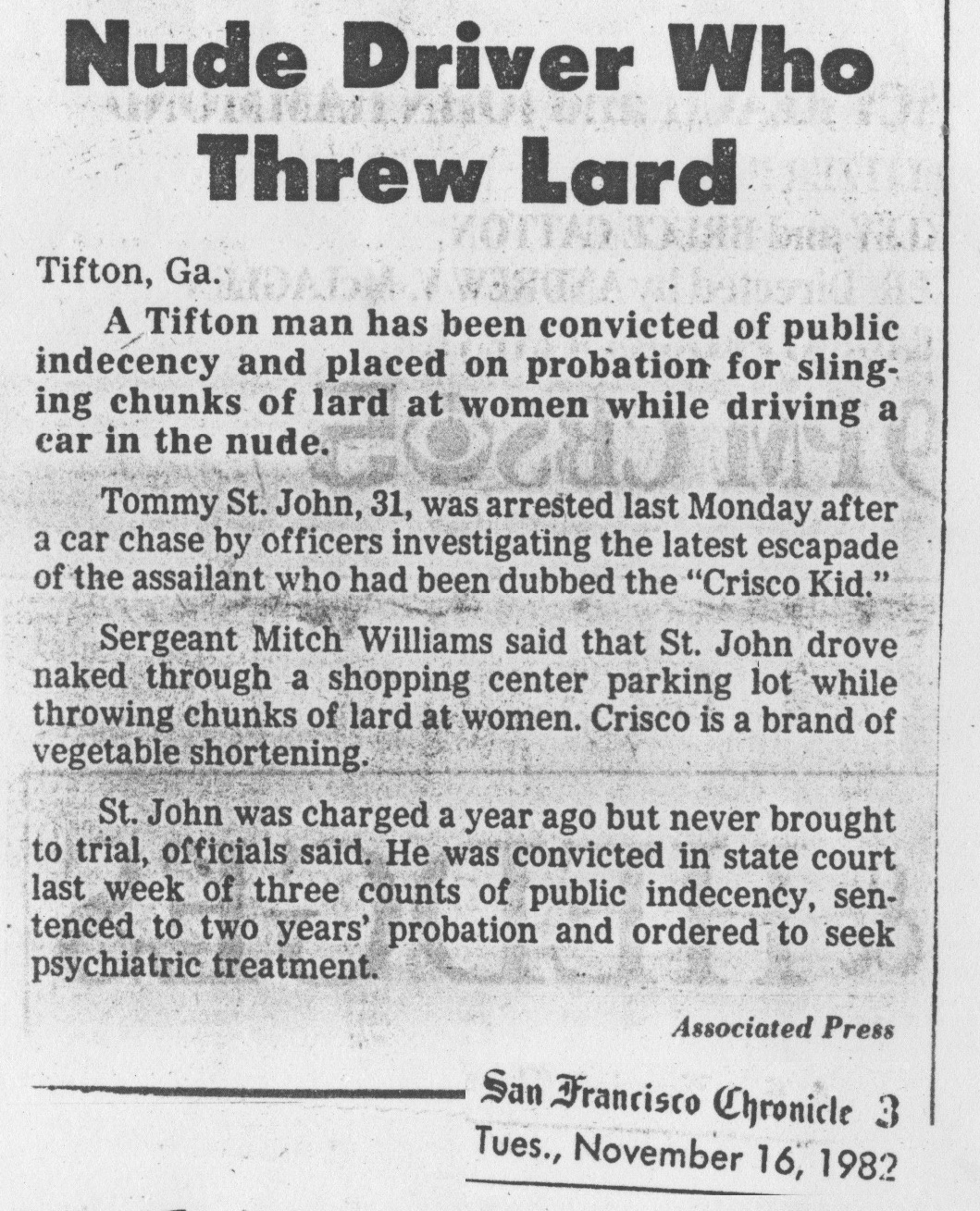

Bonus material in both the book and exhibit includes a sampling of Williams’s poetry, which often took the form of found art—recitations of words and sentences and stories that caught his fancy. I particularly liked the page in the book devoted to his rendering of “Nude Driver Threw Lard,” a brief account of a classically small-town crime story that I happened to have clipped from a newspaper in 1982. It captures the eccentricity that drew Williams to this material, even if from today’s perspective it may be less the superficial eccentricity of some of these artists that we appreciate than the core creative talent. Both actually come through strongly in the book, as well as Williams’s own.

This review originally appeared in The Outsider, magazine of Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art.