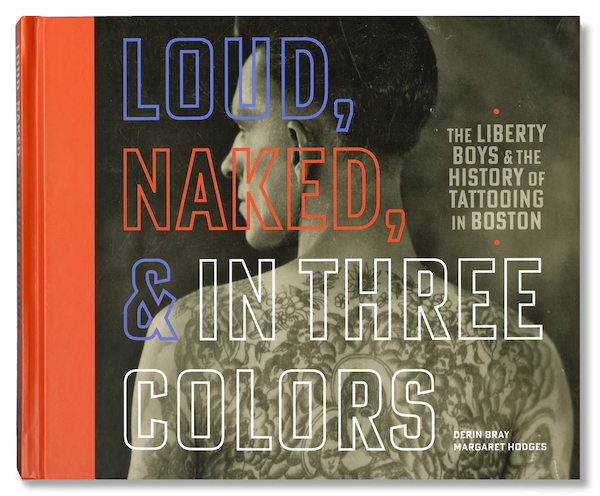

Loud, Naked, & In Three Colors: The Liberty Boys & The History of Tattooing in Boston, by Margaret Hodges and Derin Bray. Rake House, Portsmouth, N.H., 160 pages, 2020. ISBN: 9780578758404. Hardcover, $70

This volume presents a nicely balanced combination of tattoo art and tattoo lore. The book by its own account “looks beyond the connoisseurship of historical flash art” to tell the story of the tattooers, “an often transient, marginalized group,” which it does effectively, in the form of one family.

The 70 pages devoted to flash art aren’t bad, but the most exceptional part of the book is the intimate story it tells about the Liberty family, a father and sons who were Boston’s pre-eminent tattoo artists in the mid-20thcentury.

Edward “Dad” Liberty was creating tattoos as early as 1915 and was plying the craft in Boston no later than early 1919. In later years, sons Frank, Harold and Ted all followed him into the trade.

The Libertys hailed from nearby Lowell, Mass., and Harold Liberty, one of the sons, maintained the tradition even after Massachusetts outlawed tattoo shops in 1962. Harold relocated to Salem, N.H., just over the state line and less than an hour from Boston.

The family, whose descendants’ cooperation enriched this book, operated bowling alleys and shooting galleries before taking up the needle. Tattooing seems like it was a natural progression given the family’s involvement with entertainment for the masses.

The book features lots of photos and details about the colorful places the Libertys worked, especially Scollay Square, Boston’s down-market, long-gone and much-lamented entertainment district. It was removed wholesale in the 1960s to make way for the Government Center urban renewal project, widely reviled although beloved among devotees of brutalist architecture.

The photos include vintage tattoo shop signs and storefronts as well as pictures of “Dad” Liberty and one of his masterpieces, the wall-to-wall tattoos he did for Cassius Church—an eagle, horseshoes, a Madonna and much more.

The book is, of course, enriched by many pages of tattoo designs. Most of the flash in the book was not created by a Liberty, but many were owned and used by a Liberty. The authors note that the tattoo world was characterized by a high degree of sharing, at least across different geographies. And the designs that are attributed to a Liberty are as interesting and often as accomplished as the rest.

As collectors of flash have known for years, these sheets of prospective tattoo designs can be dense with creativity. They also are occasionally dense with offense. The authors point out that some “designs tend to reflect the casual sexism, racial stereotyping, and clumsy sentimentality that have permeated American popular culture of generations.”

Nonetheless, the 700+ newly discovered designs painted by the Libertys, Ben Corday, Frank Howard, Ed Smith and others represent a great catalog of a prime 20th-century folk art.

And if, like me, you’re not a big fan of tattoos themselves, it’s worth noting that the Libertys did a brisk trade in tattoo removal.

This review originally appeared in The Outsider magazine, published by Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art.