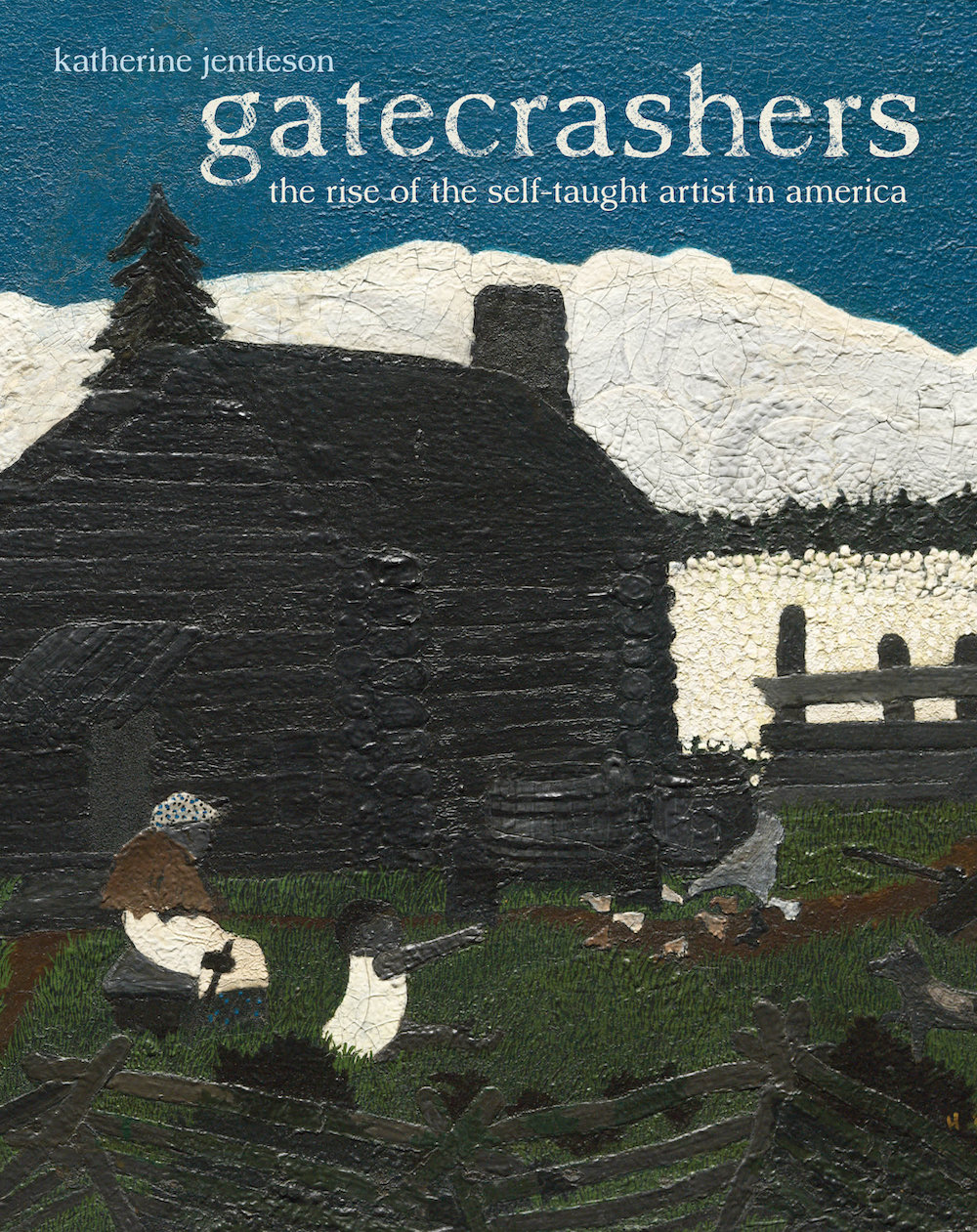

Gatecrashers: The Rise of the Self-Taught Artist in America, by Katherine Jentleson, University of California Press, 264 pages, 53 color photographs, 18 b/w illustrations, 2020. ISBN: 9780520303423. Hardcover, $50

Gatecrashers might best be described in terms more typical of a page-turner novel than an art book—it’s a story of tragedy and triumph, of drama and historic happenings.

The overarching tragedy is the opportunity lost in the 1930s to open up the definition of art to myriad forms of creativity beyond the academy. That process seemed to be gaining momentum until it was precipitously halted in the early 1940s. It only restarted in earnest decades later, and it’s still far from complete.

Lest anyone think “tragedy” is too grand a term, consider what was lost by the artists who were marginalized. It’s not just a handful of artists who didn’t get their due. It’s hundreds, thousands of them, and, for the rest of us, it was massive cultural impoverishment.

In telling this tale, Katherine Jentleson, curator of folk and self-taught art at Atlanta’s High Museum, expands on a major theme of Lynne Cooke’s 2018 exhibit and catalog, Outliers and American Vanguard Art. But where this story was one of several themes for Cooke, it is the primary subject of this volume (and projected exhibit), told via three artists in particular: John Kane, Horace Pippin and Anna Mary Robertson “Grandma” Moses.

It’s poignant how close their kind of self-taught creativity came to being an intrinsic part of artistic modernism rather than an outlier. “Most people are surprised to learn that…self-taught artists first gained their cultural capital almost a century ago, and many are initially shocked that places like MoMA [Museum of Modern Art] were once their major supporters,” Jentleson writes.

Indeed, in the 1930s, self-taught artists found their way through the gates not only of the Museum of Modern Art but, also, other institutions across the country, from the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia to the Detroit Institute of Art and the Arts Club of Chicago in the Midwest to the San Francisco Museum of Art. This might feel natural as we live through another cycle of mainstream art institutions embracing work formerly relegated to their margins. But then, as now, there also was resistance.

Artistic muscle is the necessary, if not sufficient, condition for crashing those gates. Edward Hopper made a somewhat backhanded but still largely true case for self-taught art, when he supported Kane’s recognition in a 1933 exhibition: “In the vast sea of technically competent mediocrity that makes up the work to be selected in most exhibitions, one grabs at anything with a sign of life and this is often found in the most unskillful things.”

Skill has a relative meaning. Self-taught artists by definition are not likely to demonstrate the exact skills taught in the academy, but that doesn’t mean they are not competent. Their skills are just different. You can call their realism idiosyncratic or hampered or feel, as their advocate Holger Cahill did, that “with them realism becomes passion and not mere technique…. Their art is a response to the outside world of fact and they have very definite methods for its pictorial reconstruction.”

For Cahill and other early-to-mid-20th century advocates, the case for the self-taught bolstered by a politically inflected program of celebrating “the art of the common man.” That agenda, connected to the leftist popular-front strategy of the era, resonates with our current period’s concern with diversity and the opening up of cultural institutions beyond their traditional elite boundaries.

There was also in the early 20th century a wish to assert an authentically American creative tradition. The United States was still viewed, here as well as in Europe, as an artistic backwater, its academic art a second-rate imitation of the European variety. Embracing early American pottery, painted furniture and itinerant portraiture staked a claim for art that was fully and uniquely American, and adding contemporary self-taught artists to the mix made it a living tradition.

Jentleson makes the interesting point that “this sense of cultural representativeness—as opposed to opposition—distinguishes the U.S. self-taught artists who rose to fame during the interwar period from the self-taught European artists that Jean Dubuffet began to include in his canon of art brut during roughly the same time.”

Compare an anti-social art brut figure like Adolph Wölfli to John Kane, a native Scotsman whose immigration story and workingman’s status were presented as archetypally American. Where Dubuffet was looking to creators from the margins to replace what he viewed as an exhausted academic tradition, in the United States the goal, for some anyway, was to integrate this erstwhile marginal folk tradition into the mainstream of American art, energizing rather than eclipsing it.

Unfortunately, they wound up on the losing side of the mid-century argument about what art should matter. Our art history might have been very different—and richer—had the autodidacts not been expelled from a modernist canon built narrowly around the hegemony of abstract expressionism and its offspring.

The cost of that expulsion was especially high, because there was nothing like today’s alternative field of outsider art to provide sustained institutional support and a marketplace for artists working outside the canon and for people interested in their work. The poisonous segregation of the self-taught from other kinds of artists also contributed to the vast waste of energy devoted to contending over labels. Separating the self-taught and the trained and the folk has always been hard work—and fruitless.

Jentleson isn’t much distracted by the question of labels, perhaps best put to rest by the apropos statement she shares from Alain Locke, philosopher, art patron and advocate for Pippin: “Art doesn’t die of labels, but only of neglect, for nobody’s art is nobody’s business.”

Neglect may kill the art, but it doesn’t necessarily stop the artist. It is an article of faith that these kinds of self-taught artists create without regard to whether there exists an art world to appreciate and support them. The existence of supporters and appreciators still makes a difference, however.

The creative path of the three artists who are the focus of Gatecrashers may have initially taken shape independent of the art world, but all were influenced and energized by the artists, curators, dealers and collectors who welcomed them. Their eventual interactions with the art world gave them agency in developing their visions and their careers.

“At the heart of Gatecrashers is a sense that John Kane, Horace Pippin and Anna Mary Robertson Moses were more than just taken along for a ride by various constituents of the art world….” writes Jentleson. “Their ascents may have begun with sensational stories of discovery, but part of what distinguishes them from their less-successful self-taught peers was how they exploited their respective waves of interest as bold individuals with confidence in both their art making and their identity as Americans.”

Pippin was widely exhibited and accepted in conventional art venues, more so than his African American near-contemporary William Edmondson. Even though Edmondson famously was the first African American to have a one-person show at the Museum of Modern Art, that event did not provide him a sufficient art-world foothold to avoid fading mostly into obscurity until the 1980s revival of interest in self-taught artists.

Pippin had a high degree of direct personal engagement with the art world, as opposed to being mostly represented by sponsors, as was the case with Edmondson and Bill Traylor. (Living in the Northeast rather than the South might have helped.) As a result, it seems, “Pippin was the first American self-taught artist—black or white—to embody Henri Rousseau’s degree of participation in his own success, not only entering his works in competitions but also attending his openings and engaging with other artists,” writes Jentleson. “Pippin did not see himself as existing in the shadows of modern masters. And he was right.”

Even more than Kane, who she believes ramped up production of urban scenes in response to their popularity, Pippin had a “powerful consciousness of what it took to succeed as an artist…especially one who was doubly marginalized by his lack of formal training and the color of his skin.”

Perhaps as a result, Pippin, like Rousseau, maintained his foothold in mainstream museum collections even as those institutions turned away from self-taught artists generally. Pippin and Kane both attained reputations as serious artists, but Grandma Moses remains a kind of outlier. Her enormous popular success at the start of her art career in the 1940s, combined with the upbeat affect of her art, are not a recipe for credibility among cognoscenti, then or now.

Moses was drawn—perhaps willingly—into a bit of a culture war around modern art. “What’s the sense of making something to hang up on the wall if it isn’t pretty?” Moses told Life Magazine in 1948. That attitude didn’t play well for an art world placing its bets on abstract expressionism and its highly intellectualized successors. That world preferred, and still prefers, artists who embrace anxiety and dislocation rather than offering salves—though one might think there ought to be room for both. Moses hasn’t fared that much better in the field of self-taught art, where she is still something of an outsider, especially in the art brut wing.

That’s despite heavyweight support, including representation by the prestigious Galerie St. Etienne. Her paintings also found appreciation in Europe. The peaceful life and warm interiors were “presented and received as a form of spiritual refuge in European cities ravaged by World War II,” Jentleson notes. (Salves have value for the wounded.) Even if the favorable European reception was at least partly due to “certain European prejudices about unsophisticated Americans,” that did not exclude nuanced appreciation of the art, as more recently embodied in the writing and advocacy of St. Etienne gallerist and author Jane Kallir.

There have always been compelling reasons to include all these artists under the big tent of modernism, as their advocates tried to do in the 1930s and early 1940s. Technically precise naturalism, after all, was no longer the standard for quality art. “So far as realistic effect is concerned [these artists] are in harmony with the best contemporary practice,” Cahill wrote in 1938. “They are devoted to fact, as a thing to be known and respected, not necessarily as a thing to be imitated.”

But what these artists perhaps most shared with other pioneering modernists—more important than technical skills or shared aesthetic and cultural influences—was the freedom to paint what they wanted the way they saw it, without regard to the burden of art history.

This review originally appeared in The Outsider magazine, published by Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art.