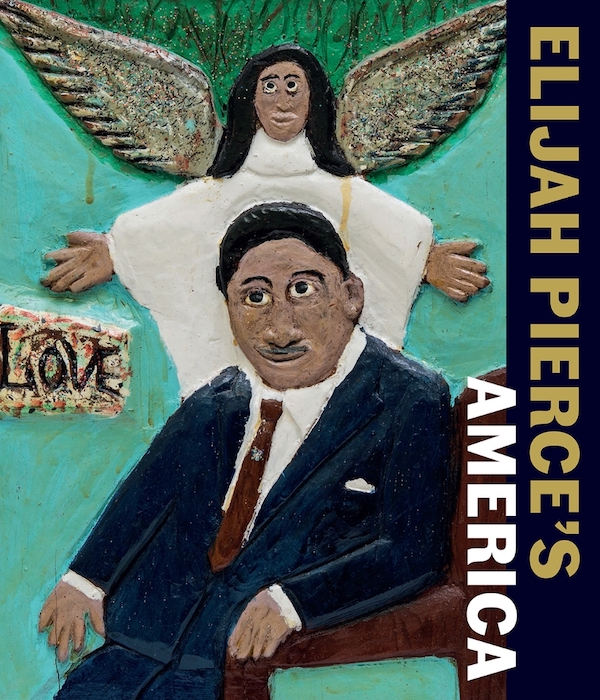

Elijah Pierce’s America, edited by Nancy Ireson and Zoé Whitley, with contributions by Sampada Aranke, Theaster Gates and Michael D. Hall. The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, in association with Paul Holberton Publishing, London, distributed by the University of Chicago Press, 208 pages, 120 color plates, 2020. ISBN: 9781911300878. Hardcover, $50

To the long list of reasons to resent the pandemic beyond death, sickness and unemployment, of course, we can add missing the opportunity to see Elijah Pierce’s carvings in person at Philadelphia’s Barnes Foundation.

The retrospective ran from September 2020 to January 2021 and included more than 100 works. But pandemic era travel restrictions prevented even ardent admirers from making the pilgrimage to Philadelphia. No matter how impressive the catalog, the master carver’s reliefs and sculptures really need to be seen in person to be fully appreciated. There simply is no way that photos can do them justice. And this book does have fine photos, well shot and generously sized. So, in the spirit of make-do, it’s a delight to see this work, and it’s great to have a record of this important exhibit to sit alongside the catalog for the 1992 Columbus Museum of Art blockbuster Elijah Pierce Woodcarver.

The Barnes show isn’t as big, but it includes some pieces that were not in the earlier exhibit, including a black Popeye and a great autobiographical relief of Pierce fleeing a Mississippi lynch mob. The earlier catalog boasts more scholarly depth than this one, but the new volume includes new generations of insights in its essays and a number of fine historical photographs of the artist.

The complexity of Pierce’s imagination comes through clearly. Of course, the creations of any artist who does not participate in the twisting and turning discourses of contemporary art may seem simple by comparison; however, the absence of that arcane conversation does not make the work simple.

Essayist Zoé Whitley takes appropriate aim at the cliché that “simple” is a hallmark of art by self-taught creators. “The apparent simplicity of his compositions belies a host of intertwined personal and collective references, legible to those who seek them,” she writes.

As with Bill Traylor, there is a tendency to simply not see what one does not comprehend.

This review originally appeared in The Outsider magazine, published by Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art.