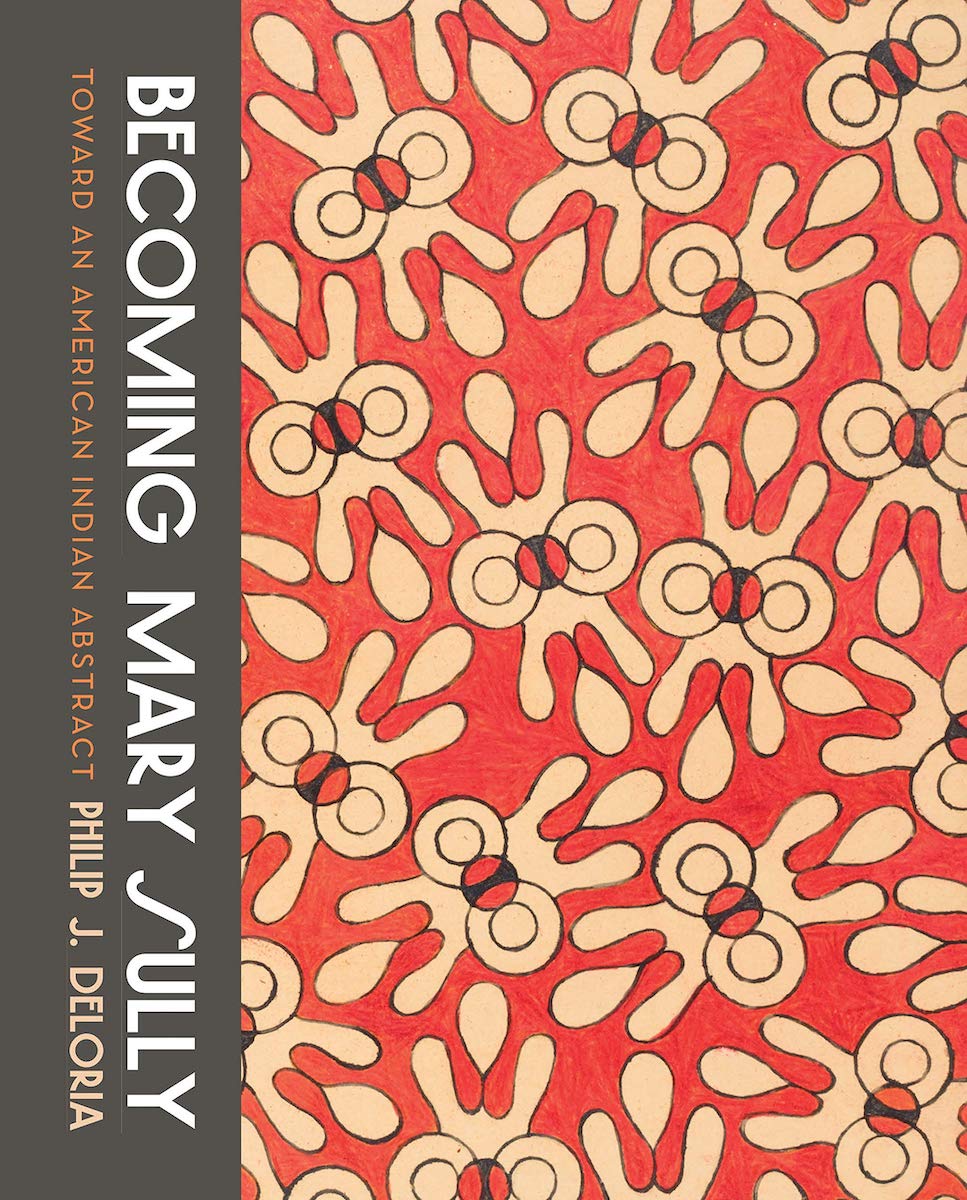

Becoming Mary Sully: Toward an American Indian Abstract, by Philip J. Deloria. University of Washington Press, Seattle, 336 pages, 221 color illustrations, 2019. ISBN: 9780295745046, Paperback, $34.95.

Mary Sully’s story is a saga of identity, from her signature artistic project — 134 iterations of what she called “personality prints” — to her name, which was actually Susan Deloria, to her ancestry, which gets complicated quickly. Indian and Anglo, it included tribal leaders and a military officer who slaughtered tribes. There is also a famous painter in her lineage and, not surprisingly, a lifelong struggle to find a place for herself.

Deloria’s creative history has the makings of outsider art tropes. Born in 1896, she was compulsively shy, personally difficult and possibly bipolar. She was largely self-taught as an artist, we are told, and certainly received little institutional artistic support beyond that provided by how-to books. She produced a body of work that mostly went unseen, apart from some informal showings at Indian schools, apparently organized by her sister and herself. Then, rediscovery decades later revealed a unique, dramatic and highly creative personal vision.

That’s all to the brut, yet there was that famous portraitist great-grandfather, Thomas Sully, whose name she took and whose subjects included Andrew Jackson as seen on the $20 bill. There were attempts, apparently abortive, to take college-level art classes. There was what must have been a fairly cosmopolitan upbringing in a family that was prominent in the Native American community as well as in the Episcopal church. There’s an intellectually powerhouse sister, Ella Deloria, with whom Sully lived most of her adult life; a nephew, Vine Deloria Jr., who was an important writer (Custer Died for Your Sins); and Vine’s son Philip Deloria, who is a history professor at Harvard and author of this book.

With no formal background in art, that last Deloria was not a natural to write an art book. But he consulted widely, he says, and has clearly studied closely. Most important, his great aunt’s life’s work, contained in a box left in his mother’s possession, gripped him when he finally engaged with it decades after Sully’s death. The richness of her identity, both in her life and her art, also happened to line up with his scholarly interests, in particular the relationship between Indians and modernity.

The book thus explores not just Mary Sully’s art but goes deep into Indian culture and its relationship with art history and American history generally. Deloria also delves into Sully’s sister Ella, an important player in the development of cultural anthropology in the United States and a fascinating figure in her own right.

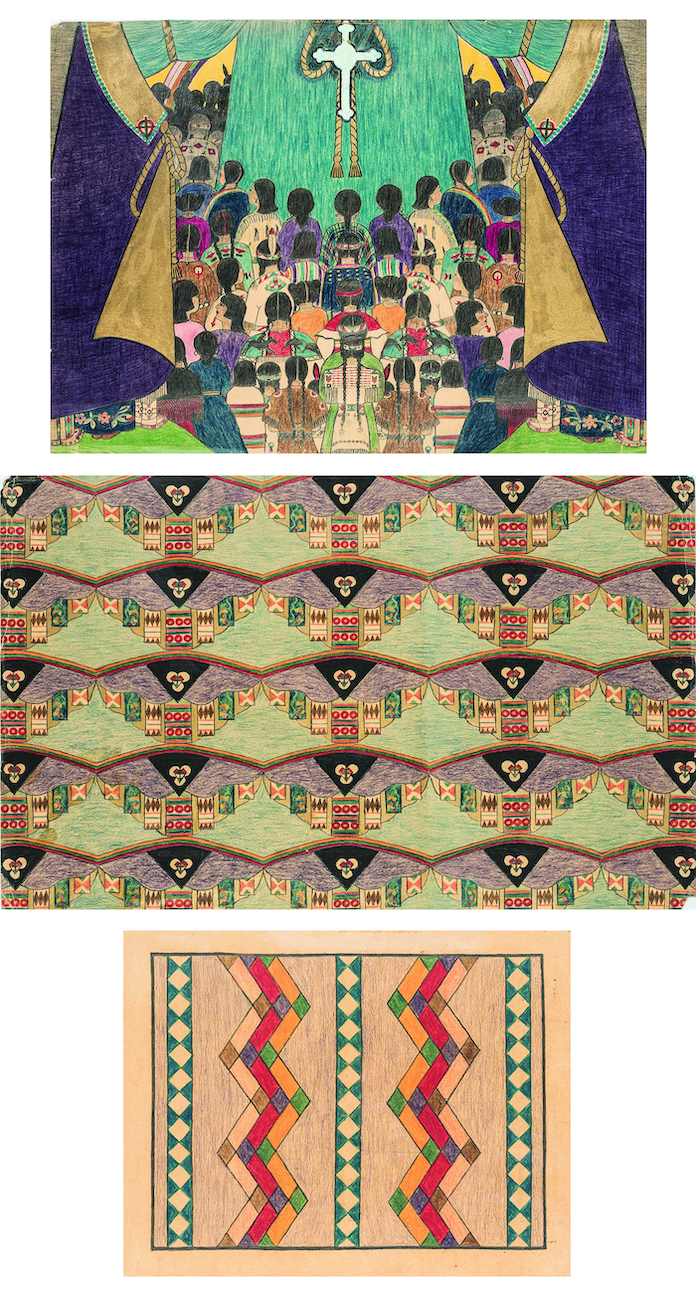

Deloria’s interest in Sully’s context and broader significance does not prevent him from giving the art its due. He undertakes close readings of a number of her personality prints. These constituted a highly personal project in which she represented leading figures of her time, from Amelia Earhart and Patsy Kelly to J. Edgar Hoover, Shirley Temple and Thomas Edison, among many others. She also illustrated impersonal subjects such as the Red Cross, Good Friday and “Three Stages of Indian History.”

As Deloria makes clear, in part it was Sully’s very isolation from the art world and its infrastructure that made such a project possible for someone of her background. An Indian woman plumbing celebrated fame and accomplishment via a highly idiosyncratic combination of modernist design and Native American abstraction was something entirely new and, in its execution, quite wonderful.

As Deloria describes it, the “dimensional experimentation, perspectival play and optical challenge, aligned [her] with artists of the early 20th century.” But her worldview and extensive use of native imagery clearly root her in that part of her family legacy.

The personality prints are all vertical triptychs, with two larger panels on top (18 inches by 12? and 19 by 12, respectively) and the smallest on the bottom (12 by 9½). Each set of images is usually identified with a person, with the top panels tending to be more representational (though not conventional portraiture), the middle panels moving further away from figuration, and the bottom panels entirely abstract and typically drawing most heavily on traditional Indian patterns.

The images are stunning—and often utterly distinctive, like the concentric circles of faces in Ziegfeld; the elegant motion in the semi-representational top panel of Fred Astaire that continues through to the wholly abstract but still elegant and energetic bottom, to the simply surreal imagery of Titled Husbands in the USA.

While Deloria presents rich background on Sully and her sister, there are still important gaps in in our knowledge of their lives and perspectives, which makes for difficulties interpreting the work. Credit to Deloria that he tries hard to extract the meaning, taking us a long way toward grasping his great aunt’s messages. Those messages had both aesthetic and political dimensions, partly summed up by what Deloria terms her “anti-primitivist Indian modernism.”

Although it’s certain that his understanding has occasional misses, they’re hardly noticeable compared to the book’s biggest problem, which is not in anything he writes but in what he is able to show. At 7½ by 9 inches the volume is simply too small. The pages aren’t big enough to do justice to the work and, even given their size, aren’t used to best effect.

If the details are only barely discernable in this diminished format, however, the power of the art still shines through. The greater tragedy of Sully’s legacy seems clear: what Deloria calls her “’one-way’ aesthetic engagement with the world. It spoke to her and she spoke to it, even if that world had few opportunities to listen.”

Indeed, for decades after Sully created the work, no one heard a thing. She died in 1963, her sister in 1971. The work was put in a box and passed through the hands of relatives to the author’s mother, who kept them safe for decades. Deloria recalls seeing them in his youth but commented to the Harvard Gazette, “In the ’70s they were mystifying, and we couldn’t make sense of how they worked; when we pulled them out in the 2000s and you could Google people, they took on deeper meaning much more rapidly….

“I went from thinking, ‘She’s my oddball great aunt’ to thinking, ‘She’s really a genius.’”

Now, through his efforts, including this book, the world is finally getting the opportunity to listen and to start to grasp that genius.

This review originally appeared in The Outsider, magazine of Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art.