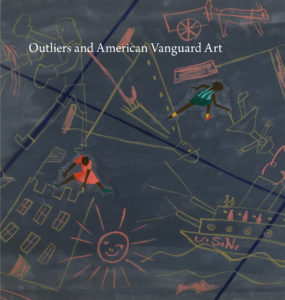

Outliers and American Vanguard Art, by Lynne Cooke. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 412 pages, 450 color plates, 2018. ISBN: 978-0226522272. Hardcover, $65

Outliers and American Vanguard Art, filling several rooms at the National Gallery of Art, is a dauntingly large-scale show. And at five pounds, 412 pages, 450-plus illustrations and a 10 x12 form factor, its catalog is even more daunting. But, despite some excess imbrications and fixed subject positions, the art and the important points being made are plenty sufficient to interest non-academic readers.

Outliers and American Vanguard Art, filling several rooms at the National Gallery of Art, is a dauntingly large-scale show. And at five pounds, 412 pages, 450-plus illustrations and a 10 x12 form factor, its catalog is even more daunting. But, despite some excess imbrications and fixed subject positions, the art and the important points being made are plenty sufficient to interest non-academic readers.

Curator Lynne Cooke’s core premise is that the story of modernism is woefully incomplete absent the art of the self-taught. Her exhibit places the work of trained and untrained artists side by side to tell a pointedly joint story — and because the pieces of art have something to say to each other.

An obvious example: The role-playing and identity-interrogating photographs of Eugene Von Bruenchenhein, Cindy Sherman and Lee Godie.

A commitment to equal footing resonates throughout the catalog and in the exhibit. Aesthetic equality doesn’t mean all is equal, however. “Art is defined not by innate characteristics but by the determinations of socially empowered agents, institutions, and discourses that evaluate, legitimate, and promote it,” Cooke points out.

While the Outliers project takes delight in the art for its own sake, its thematic focus is the way those empowered agents and the outlier artists have related over the decades. It examines not just the often-fraught power relations involved but how moments of positive institutional reception have brought attention and legitimation to valuable yet undervalued creative and cultural effort.

“The advocacy of credentialed artists for the work of their unschooled peers…together with ground-breaking exhibitions in institutions of modern art that identified, classified, and validated such work, have played a determining role in shaping the narratives of American art history,” she writes.

The inner workings of the art world and its vanguard are not necessarily points of great interest to those for whom the point of outsider art is to be free of all that (per Jean Dubuffet’s original art brut concept). It’s not just the artistes brut who stand outside the art world and its discourse, after all, but also many of the people who appreciate and collect their work — and, for that matter, most people, period.

Vanguard discourse and the self-referential art it esteems can be valuable and interesting on their own terms, but they are increasingly unimportant to the broader culture. (Dubuffet’s jeremiads against Cultural Art don’t signify so much, when it’s no longer such a potent threat to creativity.) That diminished standing is, perhaps, why the art of the self-taught is once again penetrating mainstream bastions. Much like, say, symphony orchestras, the art world finds itself having to reach out in order to hang on.

Cooke, a senior curator at the very establishment National Gallery of Art in Washington, devotes a good deal of her catalog essay to an early case study in reaching out, which became a tragically missed opportunity. It still seems remarkable that Alfred Barr, the first director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, was so passionate an advocate for self-taught art that it arguably lost him his job. Also, arguably, Barr’s 1943 demotion put the kibosh for several decades on institutional interest in folk and self-taught art — and the creative prospects of bridging elite and popular expression.

Instead, an essentially parallel art world eventually developed that revolved more or less exclusively around self-taught creators, generating its own audience (and, thus, a market) for their work. With exhibitions like Outliers increasingly embracing creative equality between trained and untrained, however, this parallel world shows signs of dissolving back into the mainstream. While there is potentially both prestige and a bigger financial upside for artists (or their descendants) and collectors, the benefits probably will flow to a smaller, more elite group than welcomed in that parallel world.

Accepting the vanguard’s embrace also means living with its forms of discourse, something not all lovers of self-taught art will appreciate. Nor is everyone in the broader art world ready to embrace this particular Other, despite incursions like Outliers. Barr’s opponents have their heirs.

What to call this stuff remains a nagging issue, and the Outliers catalog includes the obligatory treatment of terminology. While that’s often the deadliest section of books concerned with this hard-to-name art, the chapter devoted to “Black Folk Art Redux” actually manages to debate labels in ways that enlighten rather than enervate. That’s mostly because, like the overall project, it’s generous in spirit and relatively free of politics. The roundtable discussion is less about condemning or advocating particular terms than about unpacking what the labels mean and, important, have meant. Labels unloved today may have made sense in a certain time and place. Understanding what was intended rather than simply criticizing the people who used them 10 or 50 or 100 years ago might help us better understand both the art so labeled and its treatment over the years.

Cooke herself rightly seems a little diffident about introducing a new label like “outlier.” More than labels, however, she is concerned with how art world institutions and their reception of work from self-taught creators reflect the choices and biases of the people within them. She wants to understand the influence of other “empowered agents,” especially the professional artists who have been key advocates for the self-taught in every major wave of enthusiasm for this work, “embracing autodidacts without distinction, simply as fellow artists.”

A not-always comfortable but overriding point is that while many lovers of self-taught and outsider art take pride in the independence of their preferences, taste doesn’t just happen, even for the most vanguard of us. It’s very much subject to the influence of cultural biases and institutional forces. On the negative side, that includes burdening non-mainstream artists with the obligations of “authenticity,” not to mention outright exploitation. On the positive side, projects like the Depression-era Index of American Design spread awareness of American folk art, while decades later the Corcoran Gallery’s original Black Folk Art In America show helped generate interest in the art of self-taught African Americans.

University of California-Santa Barbara art historian Jenni Sorkin explores how places like the Whitney Museum took the once-radical step of taking women’s creativity seriously. She could have simply complained about how museum quilt exhibits assimilate women’s creative work into hegemonic modernist discourse, but, instead, makes a number of interesting points, among others that quilts may not be as homespun as they seem. Their makers, she says, deserve more credit for aesthetic sophistication than typically allowed to work deemed quaint. The point is to free these artists from those chains of authenticity, something the “Black Folk Art” panelists also discuss.

Jennifer Jane Marshall, an art history professor at the University of Minnesota, takes on discovery narratives, which play an outsized role in the broader narrative of self-taught art. “I examine the discovery narrative of these artists not for the facts they relay, which are often apocryphal, but for the values they encode,” she writes. (The apocryphal facts often include those supplied by the artists themselves.) Her focus on narratives from the first half of the 20th century, including “the packaging of black artists by the white art world” in the interwar years, has lessons for the packaging that happened in the last part of the century and that continues to happen today, for better and worse.

Even with the worse factored in — and Marshall shows how “discovery” can turn on “raced, classed and gendered hierarchies” — discovery is essential. By definition, art created by people who do not see themselves as artists will disproportionately never become known if not found. So, even if the narratives can be problematic, the discoveries can be quite productive for both the artists and our broader cultural heritage.

Outliers is, itself, another moment in the century-long discovery narrative of self-taught art. That’s not without risk. Exhibits that hang outsider and insider work together have been criticized as patronizing the former, valuing it largely for its influence on the latter. But while Outliers does, indeed, point out episodes of influence, that’s not its main point.

Cooke’s goal clearly is to allow the self taught full partnership in the making of modern art. That’s not so admirable to those who find the modernist narrative distasteful. But why not give the untrained their due? Whether or not you like this train of thought, the Outliers argument is coherent—and a lot better than enforced segregation—no matter who is doing the enforcing or for what noble reasons.

Nor is that full partnership mere lip service. One of Cooke’s most important arguments is that the marginal position of those marginal to the art world is not an obstacle to artistic importance. “Their position at a remove is often a preferred location, a place of strength,” the exhibition brochure says. Standing outside can enable the envisioning of work in ways that would never emerge from within the mainstream. In other words, Cooke is taking the kind of radical step that derailed Alfred Barr: Self-taught artists might sometimes produce artistically superior work, exactly because they are self taught.

This review originally appeared in The Outsider magazine, published by Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art.