Stanley Szwarc in color

When Stanley Szwarc saw three of his creations in an outsider art survey at the Chicago Cultural Center, his reaction was not entirely favorable.

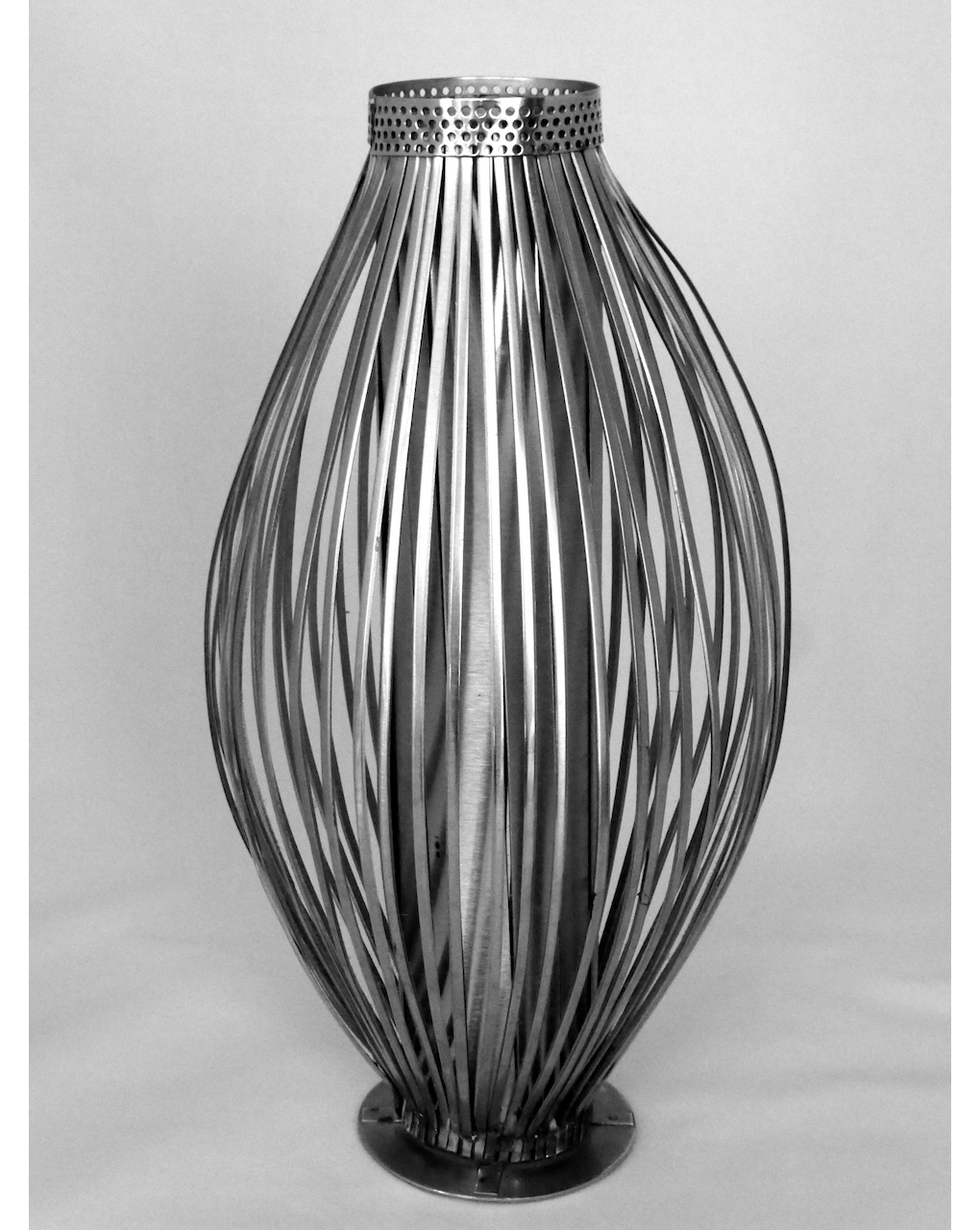

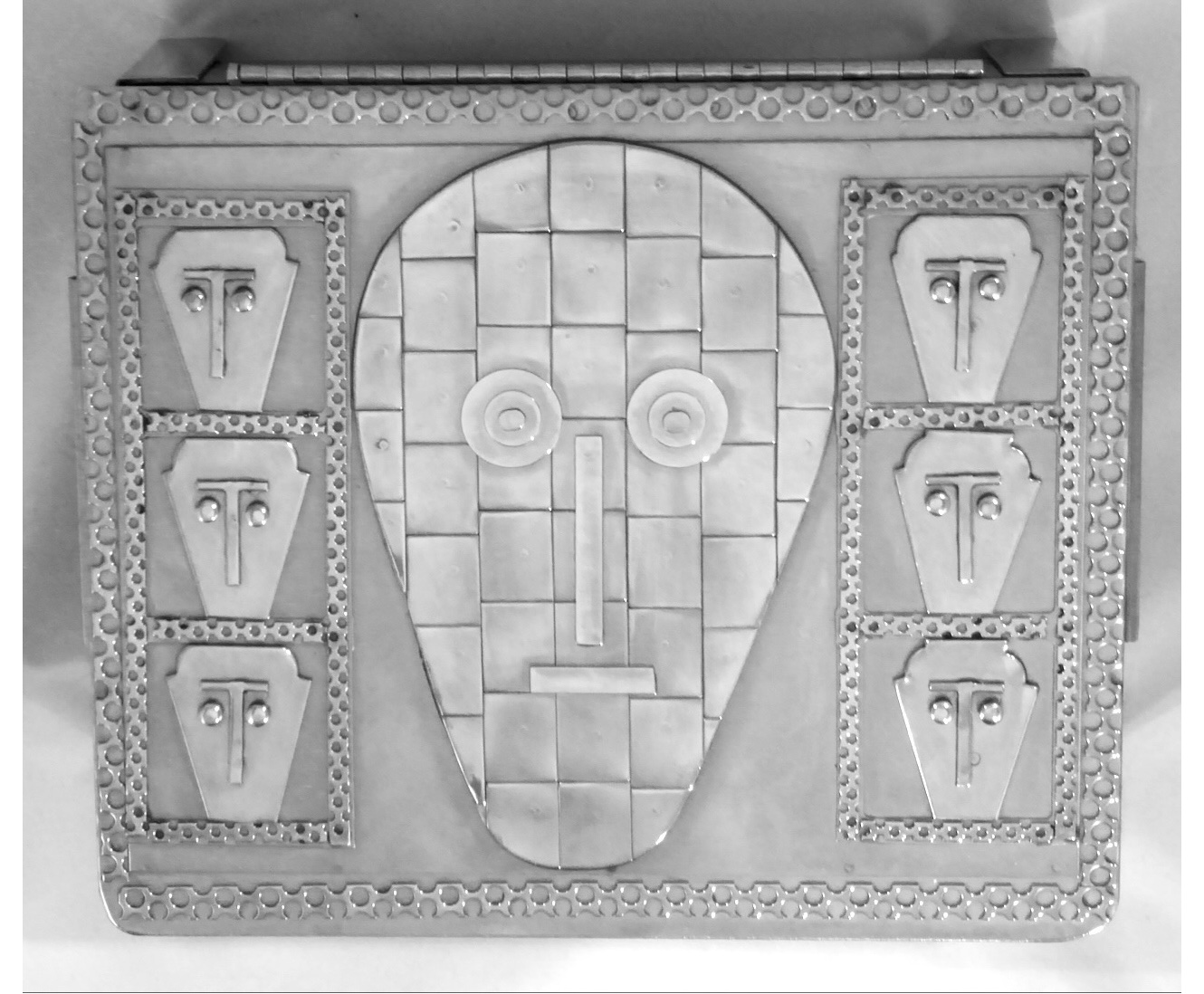

One of the steel constructions, a jewelry box decorated with a human face, badly needed cleaning. Worse, the other two pieces -- a small cross and a vase, both covered with the geometric patterns that are characteristic of Szwarc's work in stainless -- were early efforts that weren't up to his current standards.

One of the steel constructions, a jewelry box decorated with a human face, badly needed cleaning. Worse, the other two pieces -- a small cross and a vase, both covered with the geometric patterns that are characteristic of Szwarc's work in stainless -- were early efforts that weren't up to his current standards.

He was deeply flattered at being included in the show, Outsider Art: A Survey of Chicago Collections, which was sponsored by Intuit with the Cultural Center. But the two older works embarrassed him. He wanted to give their lenders replacement pieces that he felt better reflected his current abilities (and he did).

The episode was typical of Szwarc. He is modest, even flippant, about his abilities. Like many self-taught artists, he has no great pretensions about his work, despite its enormous importance to him.

"I have never considered myself an artist," he says. "I'm just a clever handyman."

Szwarc's collectors would not agree. The three pieces that bothered him demonstrate exactly why he's an artist -- specifically the extravagances of ornamentation in which his imagination takes flight.

As he layers smooth panels of metal with bits and pieces of spot-welded stainless -- quarter-inch dots, bigger circles of varying diameters, cylinders and squares, triangles and perforated strips -- sculptural forms emerge. The geometric combinations can be wildly intricate, and often evocative, despite their formal abstraction. Occasionally the patterns are figurative -- faces, plant and animal forms, airplanes and buildings.

The scale of Szwarc's work ranges from earring-size crosses to floor-standing vases. He builds key fobs, paperweights, mailboxes, stamp holders and other utilitarian objects along with the boxes, vases and crosses. Most of the pieces, especially more recent ones, are buffed to a high sheen. Some he paints with enamels after welding them together -- something of a heroic gesture considering the corners and crevices into which he has to fit his brush.

The materials are mainly recycled, brought home from the metal shop where, semi-retired, he still works four to five hours a day and where there is, he says, plenty of scrap.

"I'm still collecting, Every day I bring home something," he says. "There's so much, I can't use everything."

A look at his garage workshop confirms this: Adjacent to his power tools, including a spot welder, drill press and buffing wheel, there are dozens of tubs filled with tiny circles and squares and other scraps of metal. He's got a steamer trunk full of box pieces and metal strips hanging on the walls.

Szwarc started making art in the late 1980s, partly to keep busy at work.

They called him crazy there, he says, but "I didn't feel bad."

"I thought the pieces were very interesting.... They were looking nice, unusual."

Then, "when I retired, I was looking for something to do. I can't [just] do nothing."

Of course, those early pieces don't look that nice to him now, and he discarded many of them.

"Whatever you do, first time for sure you won't be no good. Experience counts," he says, exclaiming gently, "How many I throw in the garbage...."

Needless to say, that makes the early pieces, with their matte-finish painted surfaces, all the more desirable.

The Polish-born Szwarc came to the United States in 1977 and started working at a metal shop in 1980. In Poland he had been a bookkeeper and, in his off hours, a musician like his father.

He played trumpet and accordion in a professional Dixieland band (four men and a female vocalist). The tapes he keeps in a briefcase in his basement study reveal polished players, and his photo albums show an ensemble of Eastern Bloc hipsters (sharp suits, narrow ties and tinted glasses).

"The best I did in my life was playing music," says Szwarc, 79. "I was lousy husband. I was terrible lover. But I was good musician."

In the U.S., he played accordion for 11 years at the German-American restaurant in Glendale Heights and at other venues around the Chicago area. His last gig was at a party for Republican State Senator Pate Phillip in 1992. He has sold his accordion.

"When you are old you have to give up some things. I don't miss playing music. I can't believe it. It was a very important part of my life."

Still, the ideas in his art "are like in music," he says. "It's the bass melody and you do some improvisation. It's hard to explain. Creative mind or something. It's the same you can say about music.

"When I start I don't know what it's going to look like. I don't have any print.

"It doesn't take me long to make the design," he says. "Sometimes I don't even know where I get the idea, [but] I've got to admit my ideas have never betrayed me."

"Before I finish I see this in my mind how it should be," he says. "It doesn't work always, but mostly."

Szwarc has four children from two marriages, with 13 grandchildren in the U.S. and Europe. He shares a modest Lyons bungalow with his wife and one of those grandchildren, whom he raised as a son.

His basement is filled with photos, clocks, souvenirs and scrapbooks, as well as tool boxes he has made for himself. He can pull his inventory of boxes out of drawers, shelves and cabinets in every corner, and in his study he has carrying cases full of crosses and jewelry. There also is a work area where he paints his creations, though the assembly is done in the garage.

His basement is filled with photos, clocks, souvenirs and scrapbooks, as well as tool boxes he has made for himself. He can pull his inventory of boxes out of drawers, shelves and cabinets in every corner, and in his study he has carrying cases full of crosses and jewelry. There also is a work area where he paints his creations, though the assembly is done in the garage.

Production gets tough in the winter, though in earlier years he would wear three pairs of pants as he worked through the cold months. And when he is able to work, his production his unrelenting, he says: He can't not work. Indeed, despite the times he's threatened to give it up, he continues to be tempted back into art-making.

Szwarc's first sales venue was the indoor/outdoor Casablanca flea market on Cicero Avenue in Chicago. It was around 1988 or '89. His prices were low and his intricate artwork out of place amid the tube socks, car parts and adult videos.

Szwarc says it was William Miller, a Hyde Park writer and photographer who came across him at the Casablanca, who encouraged higher ambitions for this work. "He said the stuff didn't belong in the flea market."

"We go to flea markets all over and don't ever see anything like that," Miller says. "It's really out of place at a flea market. I was trying to tell him, 'Stanley, you can't sell these things for $5.'

"No two pieces are the same," Miller continues. "The boxes may be the same shape, but that's as far as it goes. I don't think he could do two of the same. Each has its own personal touch."

"No two pieces are the same," Miller continues. "The boxes may be the same shape, but that's as far as it goes. I don't think he could do two of the same. Each has its own personal touch."

With Miller's assistance, Szwarc placed his work in more appropriate settings, including the Illinois Artisans shop, which has a location in the Loop's Thompson Center.

Szwarc's earnings from his artwork have remained modest, however.

"If I see somebody who likes my work, it's given me a lot more satisfaction than the money," Szwarc says. "If I count my time, it's no profit. But it's something new for me, it gives me a lot of satisfaction.

"It sounds crazy but it's true. If someone likes my work, I say take it. I'm very good for work but lousy for business."

His recognition continues to be nearly as modest as his prices. Partly, perhaps, it's because the work falls into a kind of artistic void.

The boxes and crosses and key fobs show far too wild a decorative imagination to sit comfortably on the shelves of arts & crafts shops. Yet they are appear too funky to pass for high-art craft and too crafty to rate as sculpture with fine art dealers. Moreover, while Szwarc is clearly outside the mainstream art world, his work doesn't fit into established folk or outsider art genres like face jugs, whirligigs or yard shows.

In the meantime, Szwarc's imagination continues to crank.

"When I start working again I'll surprise myself," he said when interviewed one January for this article. "My computer is overloaded."

Note: Stanley, who was born in 1928, died in 2011.