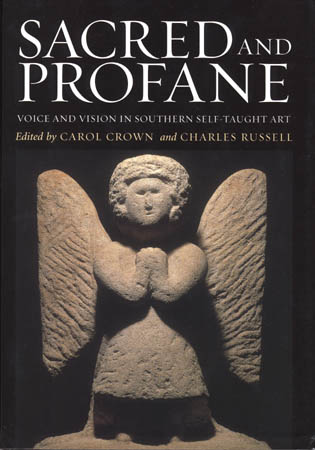

Sacred and Profane: Voice and Vision in Southern Self-Taught Art, Edited by Carol Crown and Charles Russell, University Press of Mississippi, 308 pages, 2007. ISBN 1-57806-916-5 (hardcover)

This book is definitely not bound for the coffee table, with its undersized images and serious, occasionally turgid, prose. But that’s not the point of this art book, whose admirable goal instead is to achieve a sober art-historical understanding of the self-taught art of the South “in the context of the makers’ experience.”

If it displays more rigor than most books on the subject, however, its authors are not immune to the wishful thinking and biographical bias that mar so much of the popular writing they aim to transcend.

The book gains momentum in fits and starts. Some essays will be more comfortable to scholars than to a general audience. Editor Carol Crown’s own heavily footnoted effort, mercifully unclogged with in-line citations, makes nuanced, useful distinctions across the theologies of artists like Howard Finster and Myrtice West. Despite their shared visionary evangelicalism, they speak in different theological languages if you understand what they are saying.

Benny Andrews contributes one of the least academic of the chapters, a memoir of his father, George Andrews. He makes the important point that, like many self-taught artists, the elder Andrews sustained “a dual life of doing art in the home and being like the other men in the community outside the home.” These artists may be exceptional, but they’re not all hard-core eccentrics.

Jessica Dallow’s essay on Clementine Hunter has rich detail about Hunter’s artistic development, though Cheryl Rivers’ efforts to place Hunter’s art into a broader context end up relying heavily on speculation and mostly superficial similarities that represent merely possible influences, not proven ones.

That failing is par for the course when writing about artists whose lives are often poorly documented. More distressing is the degree to which many writers seem to feel that the validation of these creators’ work as art is something to be fretted over rather than celebrated. This is most apparent in the two essays on Bill Traylor that conclude the book. Susan Crawley and Jenifer Borum deliver the most spirited and provocative of the book’s scholarly efforts, but also the most troubling.

Crawley’s essay starts auspiciously, with a justifiable slam at the loose intellectual standards so typical of writing on self-taught and outsider art. And she rightly points out Traylor’s distinct status as one of the few canonized self-taught artists who is “neither mystical nor religious.” (She might be too polite to include “nor institutionalized.”)

But Crawley seems excessively afraid of “privileging” artistic status, especially modernism. Like Borum in the next essay, and like many other serious writers on the subject, she undervalues artistic merit in favor of blackness, in this case via emphasis on a “blues aesthetic” that she works hard to recognize in Traylor’s art. Crawley points to the quality of Traylor’s thematic repetition and variation as well as to his fluidity of line and to elements of performance in accounts of his working style. “The sense of motion, change, and impermanence seems to have been as significant to Traylor as it was to the bluesmen of the Delta,” she writes. But is that enough to build a case? Crawley offers little tangible evidence other than citing more of those merely apparent affinities.

Ironically, the rejection of “formalist” art-centric appreciation seems to lead right back to that supremacy of biography. Yes, the authors of this volume use biography to demonstrate rootedness in African-American history rather than to show weirdness or charm. But their conclusions often seem no more grounded in reality than the sloppy accounts they deplore in the efforts of journalists, curators and buffs.

Borum’s rhetoric is harsher than Crawley’s as she attempts to protect self-taught artists from the art world’s elitism and exploitation. She seems even more offended than Crawley at the admission of a Traylor (or a Henri Rousseau, for that matter) into the modernist art canon. Even while condemning the notion of outsider art and the “otherness” it implies, she seems to posit a category of insiders from whose predations these others need protection, at least of the intellectual sort.

Having dispatched the dead white men of European high modernism, Borum’s venom peaks when she takes up the influential 1982 Black Folk Art in America exhibit at the Corcoran Museum in Washington, D.C. That exhibit’s emphasis on “untainted creativity” represents for her a primitivist perspective, and worse. “The legacy of this show remains the infantilization of African American self-taught artists,” she writes.

One might think that the main legacy of this show, through both its initial run and its widely circulated catalog, was to introduce Traylor and many other artists to the largest audience work like theirs had yet found. If your perspective is strictly ideological this may look marginalizing. But for the artists and the audience it was patently mainstreaming.

The “recontextualization” favored in these essays, by contrast, confines artists within the sociology of race and class, its ideologically cleansed agendas no less alien to the origins of the art than the formalist concerns of connoisseurs and curators. But why is this recontextualization fairer to the artist? Does Traylor really matter more as simply another case study in African cultural persistence, or does he come into his own as a sui generis aesthetic prodigy? Traylor’s art is exceptional in the literal sense, possessing a personal creative quality that no amount of cultural or social context can fully explain. Ultimately, it’s hard to see how valuing what makes brilliant art brilliant diminishes the artist.

One might argue that Traylor’s art is exceptional in the literal sense, possessing a personal creative quality that no amount of context can explain. However hostile you might be to the art world, why begrudge an artist of Traylor’s stature its highest accolades? Valuing what makes brilliant art brilliant doesn’t diminish the artist, nor does it require buying into a mythology of Genius with a capital G. It doesn’t even mean other contexts aren’t important and valuable.

In other words, there is nothing wrong with placing artists in their historical or biographical settings. However, to assert that this is the morally superior way to understand their work stands in need of proof. It’s all too easy to assert that aesthetic-based interpretations are marginalizing and exploitive. Aesthetic judgment inevitably has a whiff of elitism about it. But academic agendas are no less privileged and potentially no less alien to the origins of this art than the formalist concerns of the connoisseurs and curators wbo are most responsible for bringing it to the attention of the art world and the recontextualizers alike.

This book gives occasional glimpses into how enlightening it can be when authors who aspire to scholarly discipline take on the creation of outsider art. One looks forward to the day when that discipline no longer tends toward the wholesale devaluation of aesthetic activity.

this a venomous little review that does not fairly represent the book

I’m sorry the review seemed venomous, which wasn’t my intention. Disagreement, obviously, which I suppose makes it a challenge for me to fairly represent the book from your perspective.

I have a few images on my new blog with an important poll – check out “Older Posts,” at bottom, too.

While there, please consider taking the poll. It might eventually help me understand what’s going on with people. Please feel free to leave a comment or check out the links to more examples of my “outsider art photography” on Saatchi or my personal website. I really want to explore this idea; “What kind of photography makes the work outsider art?”

j. Madison Rink

And thanks for your ideas!