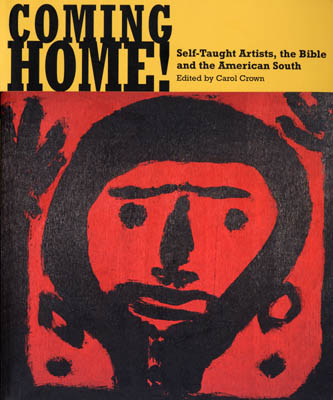

Coming Home! Self-Taught Artists, the Bible and the American South, edited by Carol Crown, with essays by Paul Harvey, Erika Doss, Hal Fulmer, Babatunde Lawal, Charles Reagan Wilson and N.J. Girardot, Art Museum of the University of Memphis with the University of Mississippi Press, 215 pages, 122 color plates, other color and b&w illustrations, 2004. ISBN 1-57806-659-X

Stereotypes have two inherent flaws: They often state the obvious and, when too generally applied, they become false. But they also are inescapable because, in the proper context, they are true.

Stereotypes have two inherent flaws: They often state the obvious and, when too generally applied, they become false. But they also are inescapable because, in the proper context, they are true.

Carol Crown’s exhibition and catalog, Coming Home! Self-Taught Artists, the Bible and the American South, can’t help but draw on Bible Belt stereotypes because they reflect a big slice of Southern reality. There is a lot more substance here than in many folk art theme shows, since the Bible really is the force behind a great deal of self-taught art.

But at the same time, the point that self-taught art of the South is full of biblical references is, because inherently obvious, not inherently interesting. It is often the job of scholars to state the obvious for the record, though, and the essays in this catalog are all scholarly in nature. That’s a virtue, since it grounds the book in actual research. A casual reader may not want to plow through every essay, but Crown’s text gives a good summary of evangelical eschatology (that’s study of the end times) and Southern Protestantism. Charles Reagan Wilson explores the religious underpinnings of the art while setting it in a broader context of Southern creativity in general. And N.J. Girardot gives special attention to the most dramatic of religiously oriented artists, the builders of monumental environments.

The broad context these essays supply is helpful, but breadth risks the second problem with stereotypes: casting too wide a net. Including in this survey a crucifixion painting by Mose Tolliver is not only banal but misleading. Tolliver seems notably unconcerned with godly matters. Ditto for Jim Sudduth, also represented in the show (with a Christ and a devil) and also basically irrelevant. The occasional appearance of religious images in otherwise secular work says little of interest about self-taught artists and the bible. It’s nearly inevitable that a cross or a Christ will show up in oeuvres that consist of thousands of works; it’s hard not to blame an over-generalizing stereotype to attach significance.

The presence of Tolliver and Sudduth images makes the absence of W.C. Rice’s Alabama cross garden, along with a number of other religiously oriented environments, even more mystifying. Rice is accounted for in the text, but that mention doesn’t do justice to one of the South’s most visually stunning, and strangest, places. Wasting some attention on the margins of Southern religiosity does not undo the truth at the heart of Coming Home, however. Religion, specifically evangelical Protestantism, is the core concern of countless self-taught artists, and many are appropriately represented in the catalog’s 122 color plates, including Howard Finster, Gertrude Morgan, J.B. Murray, B.F. Perkins and Elijah Pierce, among the best-known examples.

Unfortunately, the reproduction quality of these plates is not always equal to the fine overview of the work they otherwise provide. The highly complex Hugo Sperger painting of the Creation is too small to be of use, while the Church of God in Christ service depicted by the little-known Charlie A. Owens is too muddy to represent the piece’s actual impact. Other images more effectively represent their makers, even if most are still disappointingly small. Leroy Almon’s relief carving showing the hidden devils in his congregation demonstrates both his visual wit and his orneriness. Myrtice West’s apocalyptic paintings manage to snap through the undersize, muddy imaging to show how strong this painter can be when vision compels her.

The selection of prophecy chart paintings from a variety of artists and affords a direct connection to a fascinating and relatively mainstream religious tradition. These teaching devices created by 19th Century Adventists left a legacy as powerfully aesthetic as religious, notwithstanding the 1844 end of the world they were intended to prove.

Coming Home is at its most illuminating when accounting for these aspects of Southern religious history. While you won’t come away knowing the exact difference between the Holiness and COGIC denominations, you will have a decent sense of the devotional cultures from which the art sprang, as well as the belief tendencies of many artists.

The extent to which these tendencies depart from conventional theology gets less attention, however. The visions that so often compel these creators to make sacred art – as Finster says he was instructed by god to do – also drive them to highly individual biblical interpretations. Evangelicalism’s emphasis on a personal relationship with Christ provides fertile ground for eccentric visions, as essayist Girardot notes.

It would be wonderful for someone to untangle Finster’s theology and compare it with actual doctrine. Similarly, how can H.D. Dennis combine Masonism with bible-believing Christianity? The book references the contradiction but doesn’t explore it. Did Gertrude Morgan’s co-religionists accept her bride-of-Christ claims at face value? The respectful treatment of Morgan here, like similar respectful treatments elsewhere, doesn’t shed any light. Similar questions can be asked about any number of the artists in this book. While the biographical capsules do provide a bit of religious history for each one, almost no reference is made to the details or orthodoxy of their personal views.

The scholarly tendency to treat individuals as building blocks for a broader argument leaves specific personal beliefs mostly obscure. We’re all free, of course, to derive what meaning we can from the work itself, and there is plenty to be found in Coming Home’s examples, with or without reading the supporting text.

Asserting double meaning makes for especially free interpretation, and it’s a favorite approach when it comes to black artists, supported by the reasonable premise that slavery and racism drove African-Americans to a systematic expressive strategy of double entendre. This particularly supports the scholarly fashion today to show less interest in individual meanings than in the discovery of cultural residuals from Africa, often on the basis of outward visual parallels. That’s how James Hampton’s quintessentially personal Throne of the Third Heaven can be tied to African cultural survivals in the absence of direct evidence.

Girardot’s essay, running contrary to this trend, goes furthest among the Coming Home texts in engaging the artists, black or white, on their own terms. He contrasts, for example, W.C. Rice’s austere approach to biblical injunctions with Howard Finster’s theology, which proved so loose as to be almost ecumenical. He also takes note that many of these artists express religious views whose idiosyncrasy might isolate them from their communities more than it binds them to a common culture. His point that African survivals in Southern religion might make it more tolerant of ecstatic, visionary expression helps explain, rather than explain away, the highly personal nature of this work.

That brings into play another stereotype, that of the eccentric outsider creator. It displays the obviousness (visionary artists depart from cultural norms almost by definition) and the overgeneralization (the religious nature of this art ties it to spiritual and cultural traditions) common to stereotypes. But bridging the two worlds – the communal one of religion and the personal one of expression – can create a balanced view of these creators as well as the spiritual universes they depict.

A version of this review originally appeared in Outsider magazine, published by the Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art.