Eugene Von Bruenchenhein: Mythologies, by Karen Patterson. John Michael Kohler Arts Center, Sheboygan, 248 pages, 265 color images, 2017. ISBN: 978-0998681702. Hardcover, $65

Not everyone loves Eugene Von Bruenchenhein’s art, and, among those who do, not always equally. Some favor the paintings. Some like the photos of his wife but not the paintings so much. Others prefer the sculpture, maybe the chicken bones better, or perhaps the ceramics.

When I discovered Von Bruenchenhein, I thought the bone towers were an interesting sideline, the photos and ceramics charming, but the paintings the core achievement. Now, 30 years and a 2017 John Michael Kohler Art Center exhibit and catalog later, it seems clear that the paintings were just part of the story — the part for which Eugene himself may have most desperately wanted recognition, but neither the core of his creative achievement nor of his self-created world.

Mythologies, the name of the exhibit and its substantial catalog, makes a holistic case for the artist. When you see the breadth of objects he made, supplemented with extracts from his writings, the paintings come to seem like just one facet of his unimaginably intense drive to create. Or, to put it another way, the heart of the art is not in any of the individual forms he fashioned but in that drive and the ideas that energized it.

As Lisa Stone writes in her catalog essay, “Von Bruenchenhein was deeply curious about the order, structure, and nature of the world and the universe beyond, and perhaps the spaces in between.” He seemed to use every means available to him to express and fulfill that curiosity, his modest education and even more modest wealth be damned.

Although Michelle Grabner, in her essay, sets herself the task of “appraising his singular vision within the discourse of contemporary painting,” she is most helpful in connecting it to his contemporary world, especially the rise of the nuclear threat.

She observes that prior to 1954 he seemed mostly to concern himself artistically with “traditional genre studies [that] reveal no particular talent or skill set for the technical underpinnings of observational painting.” So how did an apparent Sunday painter of modest talent become the Eugene Von Bruenchenhein we now know?

The answer might be in his 1954 work The Danger We Face. It is the first one laced with the mushroom clouds that came to populate his other paintings starting that year — two years after the original hydrogen bomb test — all painted in his now-familiar brightly expressionist visionary style.

It’s a “trove of paintings that picture the awe of humankind’s geophysical experimentations,” she writes, adding, “along with the rest of the First World population, he struggled to understand the destructive forces of thermonuclear weaponry (and the normalizing of doomsday scenarios in everyday life).”

It is indeed hard to overstate the combined awe, horror and fear that nuclear weapons inspired in most of the population all through the Cold War. (And one could argue that Von Bruenchenhein’s paintings remain relevant because that awe, horror and fear ought to be just as pertinent today, since the weapons that inspired them never went away.)

It was not only the big questions that concerned him. Brett Littman’s essay explores the botanical influences on the artist and his imagery, an influence represented at the Kohler, not just in the ceramics and other art works, but in two actual greenhouses, representing Von Bruenchenhein’s fascination with succulents.

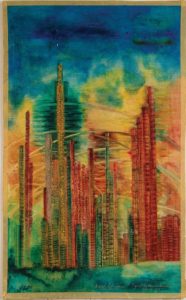

He also came down to earth in his architectural interests. As Stone explores, later in his painting career he backed off from the architecture of the universe to the architecture of buildings and cities, though still rendering them in his visionary style.

Stone quotes his writing on the back of one architectural painting: “Built of non-corrosive permanent / Color stone. / Color all thru the stone, non erosive / A New formula.” Like so much else, he took architecture seriously. And, in contrast to the despair that lies beneath the surface of his H-Bomb paintings, the architecture seems to represent a visualization of hope.

“The tower paintings reflect a desire for architecture to fulfill critical human needs and longing: for shelter and freedom, for ethical values, for living space and dream space,” writes Stone, who also points out visual parallels between the skyscraper paintings and his chicken-bone towers.

Stone’s essay brings nuance to this late group of architectural images which, like many of Von Bruenchenhein’s paintings, can tend to run together visually in the absence of close reading for distinctions. Looked at carefully, though, there is much to ponder.

And what are you likely to find if you ponder deeply? Is his genius purely in the aesthetic wonder of his creations, or did he have something meaningful to say as he attempted to conquer the geometry of time and space? It’s a similar conundrum with many artistic visionaries — how seriously to take the content.

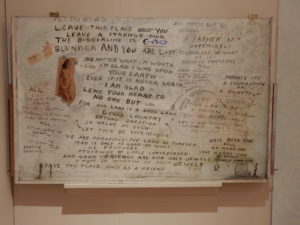

Perhaps he was just the genius to sort out the nature of the universe. The exhibit demonstrates that this man’s brilliance went beyond the surface appearance of his art. The many writing samples — poetry, letters and more — not only provide context but give a more direct sense of how he thought about himself, his wife and what he was doing.

His writings (and other ephemera on display) provide a window into something darker, the tragedy, really, that this was a man of immense energy and talent that the world didn’t care about. His efforts to gain exposure for his art came to naught. It was, classically, after he died in 1983 that the art world began to recognize something special was going on in that small house on the west side of Milwaukee.

It is of no small importance that he shared that house with his wife, Marie, featured in the hundreds of photos that some consider the most appealing of Von Bruenchenhein’s work across the various media.

But, as in so much of his art, there is something not entirely comfortable in the Marie images. It’s to curator Karen Patterson’s credit that she uses prime territory in the catalog to take them on. She departs from the traditional art catalog academic essay format, casting her thoughts in the form of a letter to Marie. That helps her raise some tough questions, questions made tougher because they can’t really be answered.

She wants to feel a connection with Marie, and she wants to know how Marie as her own person (rather than just muse to Eugene) fits into the story of Von Bruenchenhein’s art. Yet as she acknowledges in a footnote, “including Marie in her husband’s legacy is less about reversing the facts than about reading between the lines and between the lives.”

When you look at those photos, it’s hard not to ask whether she was simply her husband’s subject/object or somehow a co-creator. It’s known that she hand tinted some of the photos herself, and some of them hung in her house, but was she involved in choreographing what had to be carefully planned sessions, or was she just raw material for Eugene’s art?

His writings, Patterson points out, display an “all-consuming, grandiose sense of self.” She wonders if there was room for Marie inside his genius, not just in his images.

There is indeed a claustrophobic feeling in much of Von Bruenchenhein’s world, not just for Marie but for at least some of his viewers as well. There’s a prickliness to his work that can cause discomfort. It is perhaps no coincidence that this artist who loved cacti filled his paintings and drawings with piercing angles and spikey endpoints. The bone sculptures have their own spiny shapes, and even some of the Marie photos feature pointy-tipped crowns.

So, if not a comfortable or comforting genius, Mythologies does effectively make the case that he was a genius, nonetheless, love his art or otherwise.

All photos from the John Michael Kohler Art Center‘s Mythologies show and catalog.

This review originally appeared in The Outsider magazine, published by Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art.