Chicago is home to what might be the world’s greatest urban concentration of outdoor stone carvings. Few know it exists, and much of it has been destroyed in the last 20 years. But if you look down at the right time, you can see thousands of carvings cut into the giant limestone blocks that still survive along some of the city’s lakefront.

Media is paying attention

- Article in the Chicago Reader

- Article on WTTW.com

- Interview on WGN-TV

- Rick Kogan in the Chicago Tribune

- Interview with Rick Kogan on WGN radio

- Monica Eng in Axios Chicago

- Interview with Sylvia Perez on Fox 32

- Christian Belanger in the Hyde Park Herald

The carvings span decades, subjects and styles. The fully realized images range in size from a few inches to several square feet and include faces, profile and frontal; bathing beauty miniatures; architectural renderings; a few elaborate tableaus; a whole menagerie of animals that includes fish, birds, bugs, a sphinx, lions and horses, among others; and any number of miscellaneous subjects.

There also are countless graffitied initials and lover’s hearts, some stunningly executed. And one name or set of initials can serve as a point of attraction for later memorialists, with dozens of letters and names accumulating on a single stone. Unlike the majority of the representational images, quite a few of these are dated – the earliest to be found having been carved in 1931. The earliest carved date of any kind is June 1930.

In general, the style and weather-smoothed edges of many carvings indicate that they were mostly executed in the middle of the last century, though some are much more recent.

At one artistic hot spot just north of Foster Avenue Beach well over 30 carvings reside on a group of 20 rocks. Scores more can be found north and south of the beach. Some are clearly the result of casual scratching at the stone; others reflect sustained efforts. Either way, the hundreds of anonymous individuals who created this art did it to no particular effect, of necessity just leaving it exposed for whoever might bother to pay attention. And exposed to the hazards of time and fortune. Some of their work has been marred by spay-painted graffiti, some damaged by the erection of signs or other lakeside accouterments, some lost to natural erosion, and many further south were disappeared in the name of shoreline improvement.

Some of the carvings are thematic, at times cryptic. One shows a television set, a dollar sign on its screen and NIX$ON (sic) engraved underneath. Just to the right someone has chiseled “Dead Ha-Ha” under the three crosses of Calvary, and to the right of that is a fish — all on the same stone block.

Some carvings are more recent than the Nixon commentary. The creator of a dozen extremely complex images in a Mayan style could be seen sculpting them in the 1990s. The sharp edges and white outlines of even more recent carvings show that people continue to leave their marks along the lake, including one carving in Jackson Park dated 2016..

More visible than the carvings are paintings and drawings. These can range from cartoon characters like Mickey Mouse and the Pink Panther to landscapes, abstracts, tributes to the dead, gang graffiti (of course) and lengthy extracts from beloved poems. But paintings and drawings have a lifespan sharply limited by the elements. Even fairly recent creations exist in various degrees of fade.

It’s strange that these artistic treasures line Chicago’s best-known amenity yet remain almost invisible, other than the occasional painting that can be hard to miss. Some of the carvings are hard to decipher because of weathering, but most of them are quite striking once you notice they are there. Other than a bit of publicity in the early 1990s when Aron Packer exhibited his photos of the work, wrote about it, and gave some walking tours, there has been almost no public recognition. Hundreds of thousands of people picnic, sun and stroll along the lake, but it’s doubtful that more than a few have noticed what they are sitting or stepping on.

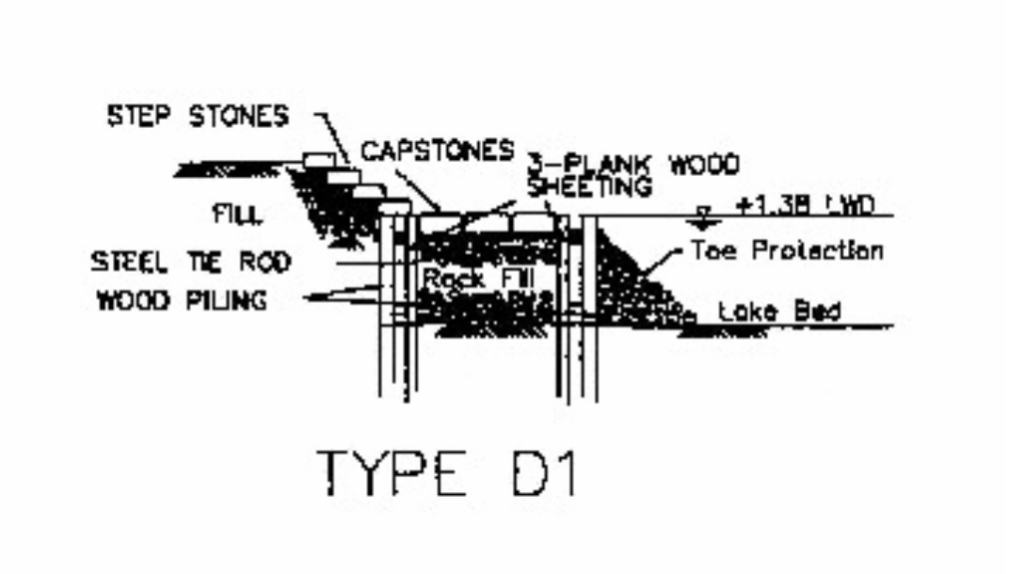

That means that most also didn’t notice the disappearance of hundreds of carvings in a massive anti-erosion project that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers undertook in the late 1990s into the 2000s. Most of the limestone blocks that bear the carvings were installed through the 1930s on a foundation of wooden cribs filled with rocks and/or concrete, according to a City of Chicago history of the shoreline. As long as the underlying cribs were covered with water they remained sound, but low water levels in the 1960s exposed the wood to the air and introduced fatal rot.

Original revetment design between Diversey and Belmont

The federally funded and directed project to address the problem was mandated, according to the Chicago Tribune, to take the most economical approach, not necessarily a reconstruction sympathetic to the cultural treasures that might be affected, especially treasures that almost no one recognizes. The city might have subsidized a more historically sensitive project – not to save the carvings but to preserve the historic character of its lakeshore. But at the end of the 20th century the money for such purposes was not to be had.

The only serious opposition to replacing the limestone with concrete was in the Hyde Park neighborhood, where community pressure led to at least a temporary preservation of the old revetment, as these structures are called, around Promontory Point. Critics claimed that the new concrete revetments proposed by the Army Corps would be forbidding and unfriendly to recreation (it does not appear that the subject of carvings came up). The preservationists, with the crucial help of elected officials including then-Sen. Barack Obama, prevailed enough to put the original plan on indefinite hold in 2006. The Promontory Point carvings have survived as a happy coincidence, but planning for a rehab of the Point is once again on the agenda, with federal funding approved in 2022. There will be a lengthy planning process, and unlike the first time around there is at least lip service to historic preservation non all sides — and the carvings have also become part of the discussion. Still, it remains to be seen to what extent the eventual project will actually preserve the old limestone.

From Fullerton Avenue three miles up to Montrose Beach on the North Side, however, the original Army Corps project has been completed. A few score limestone blocks were preserved and placed near the newly built revetments, but most are lost. And the new concrete lakefront is indeed a lot more sterile than what it replaced — and than what has survived farther north. The erosion project stopped at Montrose Harbor. For the two miles up to Hollywood Beach the stones – with their hundreds of carvings and drawings — remain. This section of the lakefront was constructed later in the 20th century with wide strips of concrete and a steel seawall between the blocks and the water.

Chicago’s lakefront carvings and paintings represent an important, beautiful, collective work of art. They resonate some with petroglyphs more typically associated with antiquity or back-country settings. But as urban petroglyphs they are unique. Stone carvings do pop up elsewhere, along the seaside in Barcelona, Spain, for example. But not in a profusion like Chicago’s thousands of sculptures.

For Chicago these carvings are as prodigious a cultural legacy as any of the city’s many assets. Perhaps someday more than just a few aficionados will recognize them.

A version of this article originally appeared in The Outsider, magazine of Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art.

There is much more information about the carvings, and more than 200 images, in my book Lakefront Anonymous: Chicago’s Unknown Art Gallery. Click to order a copy via eBay. Find a store that sells the book. Or take a look at this announcement.

Meanwhile, you can view galleries and maps for the main carving sites, read about the Hyde Park carvings or view photo galleries of the dated carvings there.

See my comments for the Army Corps of Engineers Chicago Coastal Storm Risk Management study or take a deep dive into the rock carvings along Morgan Shoal, behind La Rabida Hospital or at the south end of Rainbow Beach. There’s also a gallery of cursive inscriptions you might enjoy, and an all Bobs gallery.

I also post carving photos frequently on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/bilsw/

If you want to read more about the Chicago lakefront in general, I recommend these two books:

Lois Wille wrote Forever Open, Clear, and Free, the classic history of the Chicago lakefront, published in 1972 and reissued in 1991. Joseph Kearney and Thomas Merrill wrote Lakefront: Public Trust and Private Rights in Chicago, published in 2021. It’s putatively a legal history, but it’s rich with the politics of the shoreline, and it is extremely readable.