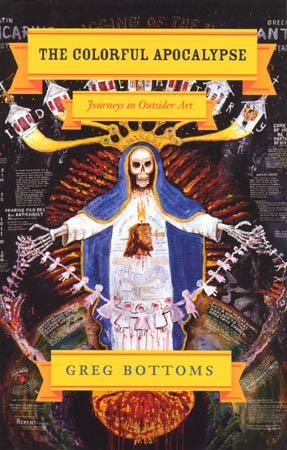

The Colorful Apocalypse: Journeys in Outsider Art, by Greg Bottoms, University of Chicago Press, 200 pages, 2007. ISBN 978-0-226-06685-1

The Colorful Apocalypse: Journeys in Outsider Art, by Greg Bottoms, University of Chicago Press, 200 pages, 2007. ISBN 978-0-226-06685-1

As an outsider to outsider art, Greg Bottoms is in a great position to ask uncomfortable questions that might otherwise run afoul of the field’s shibboleths and loyalties. Unfortunately, the questions he asks in this book are often as uninformed as they are discomfiting,

Bottoms clearly wants to engage with artists as people, not performers or freaks. Yet he ends up reducing them to some of the very clichés that he seems to want to debunk. Early on, for example, he associates Howard Finster with the myth of outsider-art craziness. He writes of outsider art (and in the context, Finster): “It is more often fuelled by passion, troubled psychology, extreme ideology, faith, despair and the desperate need to be heard and seen that comes with cultural marginalization and mental unease.”

That’s a mild variation of the more explicit claim of lunacy that Bottoms makes elsewhere in his text. That Finster was eccentric is undoubted. No one creates an environment as grandiose as Paradise Garden without being well outside the norm for avocation. Anyone who had even passing encounters with the man knew he worked and spoke compulsively, obsessed with getting his message out. But does that make him schizophrenic, or anything like it? Bottoms seems to assume that the visionary quality of someone’s art makes a prime facie case for the diagnosis, with evidence of personal idiosyncrasy the closing argument.

Bottoms dishes out equally hostile treatment to those who attempted to connect with Finster and his art. “Filmmaker and journalists, art students and hippies and intellectuals, buyers and browsers and gawkers, used to come around and ogle the old man, America’s most famous outsider artist, like a sideshow attraction or a comic performer,” he writes.

To imply that Finster was exploited is strange indeed. The assumption that country bumpkins are inevitably victims when they encounter city slickers should have been put to rest with the Beverly Hillbillies. One can argue quite plausibly that Finster knew what he was about, and played his audience brilliantly.

The effort to connect across any kind of cultural divide seems offensive to Bottoms, whether it happens on the artists’ home turf or in the museums and galleries where those dreadful hippies, art students and gawkers congregate when in town. At one point he refers to American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore as like “a warehouse of good old marginalization.”

“You, an art consumer, are invited to witness the raw expression of the marginalized and the disenfranchised, have a nice pricey meal, then go wait in the beltway traffic like everybody else in the D.C. area,” Bottoms writes.

So what exactly are you supposed to do after going to a museum? There seems to be a fundamental misanthropy here that finds ordinary human activities worthy of loathing while erecting a false dichotomy between art makers and viewers. One presumes that Finster, William Thomas Thompson and Norbert Kox sometimes have meals, sit in traffic or even go to a museum, too. They’re hardly fixed on the other side of that dichotomy unless you assume that they’re basically just nuts and that as nuts they should be shut off from the wider culture.

AVAM and the modern-day Mr. Drysdales and Miss Hathaways that Bottoms found there are at least halfway willing to take Finster and the other religious visionaries on their own artistic terms. Yes, art collectors tend to take the expression more to heart than the message being expressed. But why is valuing religious intensity as a driver of artistic vision any more hypocritical than using it for evidence of insanity? The fact that the art world’s acceptance is qualified doesn’t mean the artists aren’t accomplishing exactly what they set out to do. For many evangelicals, the mandate specifically is to preach the gospel message. If the recipients ignore it, it’s certainly their problem, not the preacher’s.

But Bottoms isn’t really any more interested in that message than the audience he berates. His real theme seems to be himself. At every opportunity he turns his account back to his family and his personal circumstances. Early on, for example, we learn that Bottoms’ grandmother was institutionalized twice for depression and alcoholism, “but, remarkably, seemed happy and at peace late in her life.” What that has to do with Myrtice West, the subject at the time, or the book’s readers remains a mystery. But we know it’s top of mind for Bottoms, not only because he wrote an earlier book on his brother’s schizophrenia, but also because of the repeated references in this work to his family history.

When Bottoms takes himself out of the picture and allows the artists and the people who know them to speak for themselves, there are some flashes of light. He includes a poignant quote from William Thomas Thompson’s wife about the toll taken by his devotion to his art and his message. Similarly, some of the quotes from Norbert Kox are as compelling as his art (even if Kox and Thompson have disputed Bottoms’ accounts of their encounters).

Given the persistent narcissism of this book, it’s hard not to suspect that the real source of Bottoms’ discomfort has to do with some internal saga of his own rather than anything to do with the art. For whatever reason, he apparently would prefer that the outside world leave these artists alone to fester in what he seems to view as their mental or cultural cul-de-sacs. It’s a nasty thought, but then in the end this book is a nasty piece of work toward all concerned.

My Own Review of The Colorful Apocalypse

and Greg Bottoms

Part One (please also read Part Two)

On page 181 of Greg Bottoms’ 182 page documentary book ” The Colorful Apocalypse “, Mr. Bottoms reveals that “a narrative is not life, and a moment in text is not a moment, only a made thing that presents the illusion of a moment. I did my best, though, to make these illusions look and feel like life, at least as I experienced it; and then, perhaps like a documentary filmmaker, I tried to string together and juxtapose some of what seemed to me to be the most meaningful moments in a way that made sense and told the story as I saw it.”

How I wish Bottoms had inserted that incredibly revealing statement on page one or even page two! Having read this admission of Bottoms belief in a new style of documentary writing or filmmaking, I clearly could have read the rest of the book with a better understanding of the intent of the writer, that to create a documentary somewhat like “a documentary filmmaker”. You see, for the most part, the book purports to detail the life and times of three powerful visionary artists each on his own mission…Howard Finster, William Thomas Thompson and Norbert Kox. And naturally, in the telling of any true story, most authors are granted an amount of leeway for imagination and trivial inventiveness. But Bottoms attempt at being a documentarian fails, falling far into the pit of his own tragic life and its colorful distortion of what lay before him but remained hidden by his laziness and his rush to satisfy grant requirements.

As I did not know Mr. Finster, my understanding of the “illusions” presented in Bottoms’ book comes from my familiarity with the art and life of Mr. Thompson and Mr. Kox. And as I do not know Mr. Bottoms save through his writings on the tragedy of his personal life and how it has colored his views towards us all, I can only deal with what he reveals about the pain and hurt and amateur psychology that most obviously will control the rest of his life and possibly that of his offspring.

Throughout the book sections dealing with Mr. Thompson and Mr. Kox, Bottoms consistently attempts to shoehorn the artists’ fervent and steadfast belief in the vision that drives the creation of their art into the same stagnant swamp that produced Bottoms’ violent and drug-handicapped brother. Bottoms seems to say repeatedly that his brother’s uncontrolled and unleashed mental disorder shares a relative with the “Christian Poor South”, a class Bottoms proudly and often reminds us that he has become “one generation removed from”. Would that he could run from his brother as easily in telling the lives of these two men but he can’t. His brother’s madness apparently stamped its image and direction on his soul and in the tips of his hands where skin meets pen. Bottoms too frequently and emphatically compares the unbending will of the visionary artist to the black insanity emanating from within his family. Initially, I believed Bottoms had practiced typical lazy writing, an affliction common to those facing a deadline or lacking any insight into their subject. But as I read and reread the book, more seemed to be at work, especially in Bottoms retelling of the seminal moment in Mr. Thompson’s life.

I have listened to Mr. Thompson many times…in person, in letters (email) and by phone…on his epiphany, the vision he experienced that has changed his life forever. That telling, the clear vision, has never changed. Never. No matter how many times I listened, the same events, the same times, the same results would reveal themselves. It is this reliably repetitive telling that has allowed me to know the truth behind the words he relates and the legitimacy of Mr. Thompson’s art as influenced by his vision. Bottoms asserts that he listened to the same man I have tell the events I have heard over and over but writes an account that clearly is “only a made thing”. However, Bottoms claims it as documentary-level truth while relaying that his new version of Mr. Thompson’s life-changing vision now has the stamp of authenticity and replaces the original. Bottoms also claims that this type of thing happens to those types of people, those people of his brother and of that “Christian Poor South” that he has proudly become “one generation removed from”. The entire section of Colorful Apocalypse dealing with Mr. Thompson’s important and driving event has been fabricated by Bottoms in the telling. Probably just Bottoms trying to “string together and juxtapose some of what seemed to me to be the most meaningful moments in a way that made sense and told the story as I saw it.” I don’t think it can be that simple.

Simple it would be to pick out little things, cast-away remarks….locked in a tower, lips painted red, a deaf mother, a Mr. T brother yelling confusing lies…Bottoms claims as truth. And simple it would be to claim these burdensome, burgeoning lies as the subjective rant of “an amateur”, of this “Camus instead of Joyce.” Oh how simple to claim the book could have been four or five hundred pages instead of the most important, the most relevant 182 pages. And as a publisher, how really simple life is when you disavow responsibility for an unrelenting page-after-page of seemingly fabricated dreams by claiming the subjective nature of the author and his quest to be free of the bonds that tie all good men trumping any right to factual reporting of “whole reels” of recordings that ended up in the trash. What simple author, one just feeling the breeze, trying to relate to the subject at hand in his own manner records hours of conversation, writes books of notes? Simple…none. No one, no writer wanting to catch the dissipating mist of an idea, the fleet-footed wing of a mood takes mounds of notes, records reels of tape. In art terms, Monet took no photographs in his attempt to show that which made him feel, a feat Bottoms and his publisher claim as the true sojourn of this wounded but courageous young master. Yet Bottoms claims to have done just that. And most incredibly, Bottoms asserts that he forever consulted those hard-copy proofs of his trek across his beloved Poor South. Bottoms claims that it was “the help of tapes and transcripts” that jogged his soaked memory, that cleared-up the hazy remembrance of his quest to show “a sliver of a sliver” of the outsider art world in a “willfully subjective presentation”. In those three words…willfully subjective presentation…Bottoms again empties his bowels of the honest and humble notion of showing that which is before you. Bottoms reveals to all his readers, unfortunately on the last page of his book, that he will stubbornly press his daggered life and times into that which he sees and hears from the two men I know in his book. Bottoms defines for the reader that he will stubbornly present that which belongs to Bottoms as the visionary force behind Thompson and Kox rather than the vision held by these two men and their presentation of that vision in their art. In doing so, Bottoms and his publisher place excessive, misleading and damaging emphasis on Bottoms’ own moods and tragedy-filled life while expressing almost total disregard for the truths of his subjects’ experience. Simple it would be to pick out the simple lies and fabrications. Simple, too, to dispute those picks, as an author or publisher, with claims of subjectivity and eye-of-the-beholder speak. But running from that stated truth eventually becomes complicated.

Bottoms has crafted a book that adheres to a tenet he claims to live by in his hobby as a “journalist….a kind of documentary filmmaker”. As he so eloquently quotes on page 122 (deep into his assault), Bottoms asserts that he will gain his story by approaching his victims with the purpose of “gaining their trust and betraying them without remorse”. Bottoms claims, in an unusual statement on how to live and, even worse, how to treat others, that this is the only way (in his role as a kind of documentary filmmaker) to make sense out of his travels amongst the people he has met. To act as a sort of confidence man, bankrupted of the quest for the true story, while wedging Bottoms’ own view of madness between himself and his subjects’ story. This is a complicated run at producing a book, at getting a story, such as the one he has created, published. Bottoms found, indeed is employed by, conspirators in his mission and others who embrace any version of a story as long as they don’t have to learn anything on their own.

I could go on and on but am becoming bored with Bottoms, his book and the lazy attempt he has created to distance himself not only from that “poor Christian South” that courses through his family’s veins but in an attempt to find in many others the madness that creeps slowly up on him from behind, in the dark corners of his eyes. I’ll close with a listing of Bottoms’ revelatory musings and will translate them so that you, his unfortunate reader, may somehow get through the book without the madness that may have afflicted Bottoms:

*

Talking about Finster, Bottoms claims to have seen a movie on him when he was a youngster but not watching it again, fourteen years later, before starting a book on the man because “In my imperfect recollection of the film( I haven’t watched it again so as not to destroy my memory with a lesser reality), Finster played …a banjer.” Translation: Bottoms views his unaided recollection as more valid than the actual recorded event so much so that he does not view the material again out of fear of getting it right. It appears that, in Bottoms’ mind, the recorded version has become the “lesser reality” and his attempt to “make sense out of what I saw” has replaced the true version. Very unusual and complicated.

*

Bottoms uses quotes by his subjects that deal with other matters in sentences wholly crafted by him to illustrate his own views. In one case, relating an AVAM meeting with a young fan of Mr. Thompson’s, Bottoms feels the fan has gotten the message of a painting wrong, that the fan is all bundled up in pimples and piercing, unable to grasp the vision he thinks Mr. Thompson meant to portray. Bottoms writes that he wonders why Mr. Thompson doesn’t “shoot fire out of his mouth” and tell the fan about “Jesus being a white guy”. Translation: Bottoms repeatedly (to quote them all would make me just as much a prisoner as to Bottoms’ upbringing as his brother has become) inserts attributions in wholly crafted views that seem to assert those attributions belong to his subjects when they are clearly created and owned in Bottoms own past and family life. In the process, because of the way Bottoms presents the text, his subjects are damaged through Bottoms own limited understanding.

*

Bottoms often and erroneously compares his subjects to what he believes are certified nutcases. In one particularly damning claim, Bottoms states that he has used his own sense of the issues to determine that Mr. Thompson is just like August Natterer. Translation: Unfortunately, the only clear link between Natterer (a hospitalized, suicidal schizophrenic who was unable to function in society and spent most of the last 26 years of his life locked away in institutions for the insane) and Mr. Thompson is that they both claimed to have had a vision. Doubly unfortunately for Mr. Thompson, Bottoms emphatically and forever has linked him with someone unable to get through life on his own, a man who claimed to read the future and predict great events, not a man who was spreading a vision not of his own making, as Mr. Thompson does in his art.

*

Bottoms refers to Mr. Thompson and his art repeatedly in marketing terms, variously referring to Thompson’s art as “currently hot”, claiming that “his eccentricity is in direct accordance to his value as an artist and he is highly valued at this time” and , in text, implying a contrivance by Thompson to engender a “hard sell” of his work and vision. Bottoms also links Thompson’s presence at American Visionary Art Museum (AVAM) with a type of cheap barkerism. Translation: Bottoms damages Thompson’s presentation of his vision through his art by repeatedly connecting Thompson’s attempts at creating on canvas that which drives him to an art world and process that Thompson cares little about and has never embraced. Bottoms claims that the most respected and presentable venue for Thompson’s work, the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore, acts like a pimp to Thompson’s supposed whoring ways. Bottoms denigrates AVAM and Thompson and holds them both up to unanswered ridicule by describing scene after scene that seems at odds with Thompson’s stated mission to get the word out about his work. Bottoms even suggests that the presence of a snack shop and accoutrements in the museum somehow invalidates all else within, including Thompson’s art

*

In one particularly indecipherable passage, Bottoms links Mr. Thompson’s concentration on his vision and work with the life of Gerald Hawkes, “a poor heroin addict from the ghettos of Baltimore” and with the life of William Burroughs, “who shot his wife and shot up in Warhol’s factory”. Bottoms does this by claiming that Thompson ignores the differences in the two nutcases work, that somehow Thompson refusal to consider their art points to character flaws in the man. No real translation for this one.

*

Bottoms, without attribution or quotes, out of hand states that Thompson would send all Buddhists to hell.

*

Bottoms assigns to Mr. Thompson an encompassing and devouring depression. Bottoms repeatedly refers to cases of depression in others, including rampant prevalence of the disease throughout Bottoms’ own addicted-handicapped family, as somehow being assigned through dictum to Thompson. Bottoms pulls the little knowledge of history of the outsider art movement he has from the black, grainy pit of his own experience and brushes across the entire field, including splashing across Thompson and his work. Translation: Bottoms lazily takes what admittedly little he knows about art, outsider art and life and decides to present this small vial of poison as the facts in his “documentary filmmaker” presentation of Thompson and Kox’s life.

Bottoms presents so much unusual text and silly links that I guess I could go on for days and days. But, as I’ve said, I am bored with this and must stop. This is as good a place to stop as any

.

Part Two

I am reviewing this book on my own, this Colorful Apocalypse, after reading it twice cover to cover, reading most of it more times than I can count and after concentrating on Mr. Thompson’s portrayal more so than the rest. As I’ve said, I know Mr. Thompson and know Mr. Kox less so. Most of my review deals with the parts related to Mr. Thompson.

It is as clear to me as the sky above that Bottoms not only has created a fictional account of the time spent with Mr. Thompson but that Bottoms has also created a message and vision that belongs only to Bottoms. In interviews conducted after the publishing, Bottoms does what most con men do when removed from their craft…they invent a persona and become it for the interviewer. Bottoms claims in an interview that “I also wanted to let them speak for themselves at length, more at length than I might otherwise, in another project.” He asserts that he documented, consulted, recorded and vetted what he wrote, that he alone respects the message these visionary artists have embraced and show in their art. He accuses many galleries and museums of attempting to “collect stories and package them and offer them up” in some unusual conspiracy of capitalism that denigrates the vision. He says that, for the most part, they miss the important message behind most visionary art and Thompson’s in particular and accuses galleries and museums of deadening the message. Bottoms, naturally, initially sees himself above all this in a way a documentarian is above advertising. But, in his pseudo artistic and martyred style designed to engender a feeling of motherly love for Bottoms, he then asks “Well, what the hell do I do?” when referring to how he spends time with his victims only to report on them later for his own enrichment.

Time after time in Colorful Apocalypse, Bottoms intimates that Mr. Thompson suffers great depression because of the way he acts and what he says but provides no proof. Bottoms states that it is wrong to equate madness with freedom, wrong to disenfranchise artists in the way AVAM does, according to him, but provides to backup to his thoughts save for the background he has dealing with a nutcase in his own family. Seemingly, we the readers, are to blindly accept Bottoms as a visionary psychologist because there exists a frightening homicidal madness enveloping his won family. He asks us to believe that he is manner clairvoyant because he has suffered under familial insanity. But, I don’t buy it. I don’t believe he sees that true nature of people anymore than a tree knows its being wet down by the dog lifting its leg right next to it. I don’t accept Bottoms cutesy, trifled style of denying his attempt at documentary writing by claiming, as he does, that he is a master memoirist, that his goal was to live with, to breathe with, to listen to his victims. The proof that he did none of what he claims in interviews conducted the book was published exists in the Colorful Apocalypse. His book damns the stated goals, the espoused life-journey-as-writer that he wears like a red badge of courage. I think Bottoms is neither documentarian nor memoirist, illuminated writer nor sparkling recorder, not insightful author nor accomplished feeling-because-I’ve-been-hurt puppy dog. I think what Bottoms has produced is a con. And that con marks him more than any claim else.

I’m bored again. Maybe more later.

OutsiderArt.info is dedicated to my lifelong friend and only partner, without whose love I would fall out of time OutsiderArt.info exists to exhibit the greatest array of art to the greatest array of people™. The site is an exhibition gallery only and makes no representation or warranty nor is a party/facilitator/guarantor to sales. All offsite links for informational purposes only. All contents copyright 2001-2007 outsiderart.info except artwork copyright respective artists. What is OutsiderArt?