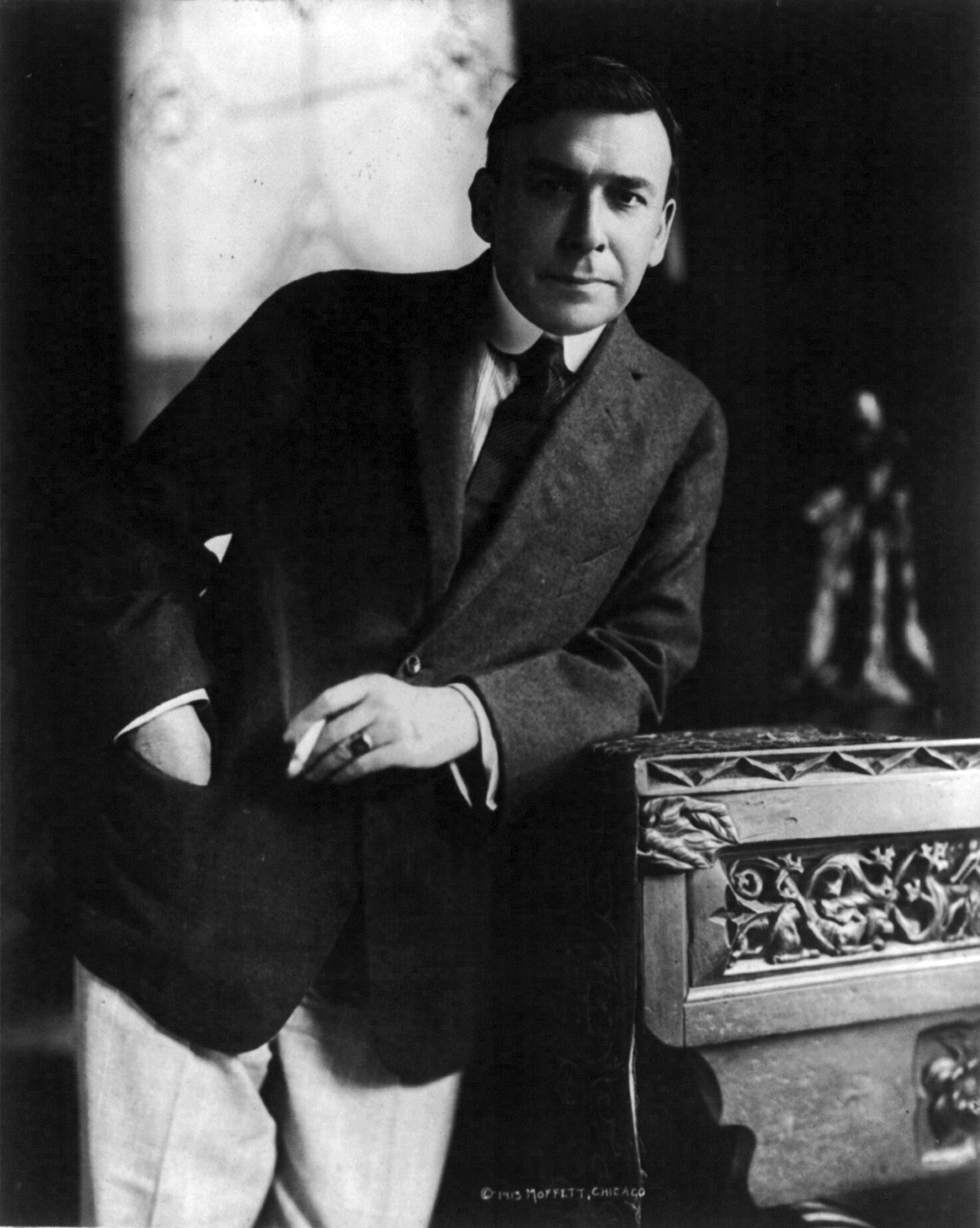

I got interested in Booth Tarkington via the credit Orson Welles gave him at the end of his Magnificent Ambersons film adaptation.

As spoken with Wellesian richness, there seemed something enchanting about the name behind this powerful story. Even in its studio-truncated form, Welles’ Ambersons was, well, magnificent, and I wanted to understand the source of this masterpiece that was both visually stunning and highly literate. A good deal of Tarkington remained in the movie, particularly the way he used bittersweet nostalgia to set up a cold-eyed assessment of advancing modernity.

I proceeded to read dozens of his books. Between the famous Strand Books in New York and the not-so-famous but still wonderful Johnson’s Bookstore in Springfield, Mass., I easily found cheap antique copies.

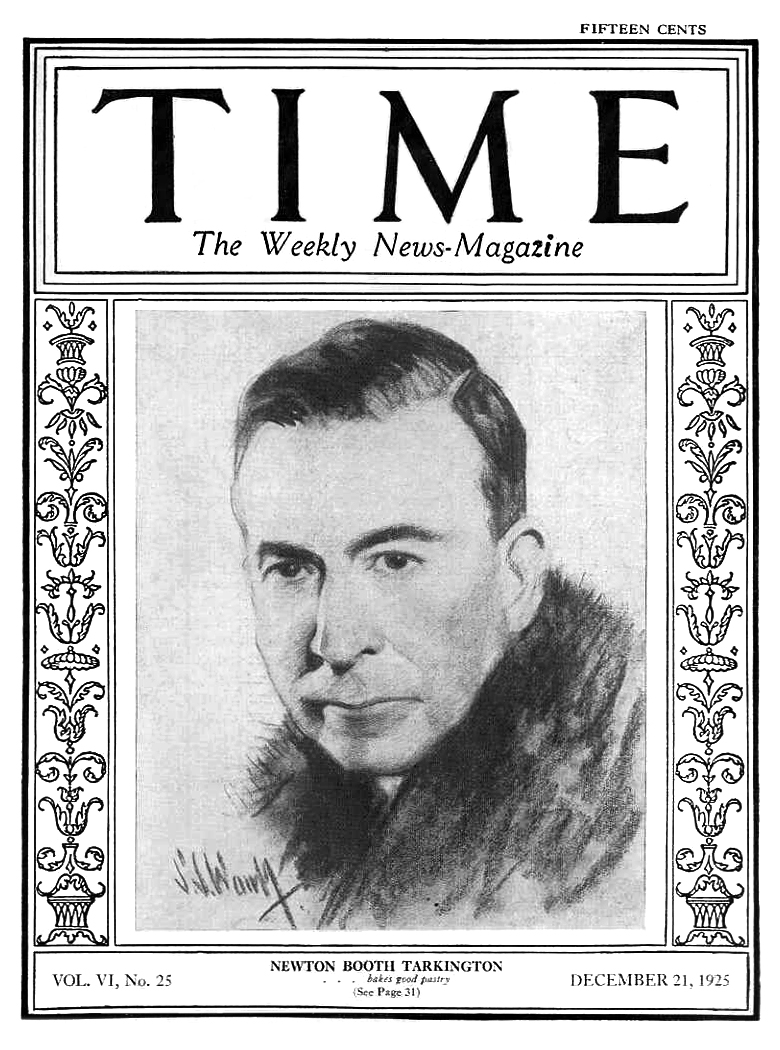

It’s not like they were flying off the shelves. In his day Tarkington was a best-selling author, but his day was in the first half of the 20th century. He was decidedly not a modernist and thus not much of a candidate for anyone’s literary canon, apart from someone committed to Indiana regionalism. I’d guess the Welles movie is the most likely way anyone becomes interested in Tarkington now, given his thorough eclipse in the world of American letters.

Artistic Discovery

Delving deep into Tarkington came easy, consistent with my taste for artistic discovery as well as a tendency to read everything I can by authors who interest me. I was proud to consider myself one of the few non-academics (or non-Hoosiers) who could pass the old Booth Tarkington service area on the Indiana Toll Road and know why it was there. (The name has since been retired – yet another indignity.)

That delving was assisted by the writing talent that made Tarkington an important author in his time. Even though now consigned to insignificance, his narrative skill is undisputed. The more old-fashioned stories that contributed to his ultimate dismissal as a lightweight, like Seventeen and Penrod, are still charming enough to entertain as period pieces. And works like The Plutocrat and Ambersons are compelling without qualification.

A few years ago, three decades after I had last read Tarkington, I returned to his corpus via the now freely available electronic versions. I started with the short fiction of Beasley’s Christmas Party, which fell on the lighter side of his writing. It helped me understand how appreciating Tarkington is like learning to appreciate your parents. The folks are bound to seem old fashioned and oblivious when it comes to what a 17-year-old cares about and they don’t. Later, you discover the naïveté was more yours than theirs. On what mattered to him, Tarkington was as sophisticated as fellow two-time Pulitzer Prize winners like William Faulkner and John Updike.

Later readers might fixate on Tarkington’s supposed nostalgia and naïveté, but they should rather have noticed the rich textures of his worlds, the revealing tensions within his characters, and the social criticism of his narrations. We all have a tendency to see what we want to see.

Flawed Indeed

That’s not to mount a universal defense of the man. He might deserve to be on an equal footing with other authors, including both his immediate predecessors and his contemporaries, but that does not always redound to his credit, for he shares their defects as well. His treatment of race was pernicious and demonstrated all the pitfalls of his privilege. His black characters were typically servile caricatures, complete with dialect. Lovable, but possessed of no inner life, just like in any number of other novels, not to mention movies as well. His handling of Jews was a bit less ignorant, but still insensitive. To say this racism was not unusual is not to excuse it, but this author should be no more written off for these deep flaws than any number of other similarly afflicted writers, from Dickens to Dostoyevsky.

On matters he cared about, Tarkington could be critical, and self-critical. Industrialization – its costs and its inevitability – was his greatest subject, and in books like Ambersons and The Midlander he makes both the distress and the inescapability come alive along with brilliantly drawn characters. He may have indulged in nostalgia, but he understood that it is often a tragic emotion.

Even in his frothier work, Tarkington’s craftsmanship creates a backdrop of verisimilitude that would have been invisible to his original audience but gives a 21st century reader a direct line of sight to at least one kind of life a hundred years and more back, before World War I soured both the world and this happiest of novelists.

Ambersons, as depressing a story in print as on film, was written in 1918 and the similarly downbeat Alice Adams in 1921. 1913’s The Flirt, on the other hand, like so many Tarkington stories, is first of all an exercise in gentleness. Tarkington loved his characters, perhaps to a fault. To his heroes and heroines he showed gentle affection, to his comic relief gentle condescension, and to his villains a mostly gentle contempt. (To a few characters his contempt could be less than gentle, with particular impatience for snobbery.)

All that gentleness throws up a fog of good feeling, but behind the fog there are crags and cliffs of unhappiness, struggle and decay. The fog can facilitate nostalgic escapism to what seems like a simpler time and place. But amid the dislocations of the early 20th century life was an uphill scramble -– Tarkington’s most persistent theme, even in his happiest publications.

Disappeared

All these distinctions hardly matter now given Tarkington’s almost complete disappearance from literary history. The small dramas afflicting provincial elites anchored in the 19th century were of declining interest as the 20thwore on. And Tarkington’s naturalistic style of fiction, meanwhile, was similarly outshone by the experimentalism and edginess favored by modernism and its descendants. Robert Gottlieb saw fit in 2019 to take another look at Tarkington’s reputation, but his New Yorker essay turned out to be more nails in a coffin that was already sealed shut. Tarkington, Gotlieb argues, betrayed his own potential by being too gentle and easy going, letting his fiction slide into comfortable irrelevance.

“What was it, finally, that kept so capable a writer as Tarkington from producing so little of real substance?” Gottlieb asked. “Yes, he lacked the fierceness and conviction of a Dreiser or a Lewis; his talent was descriptive rather than penetrating; and he was almost pathologically nonconfrontational. But ultimately what stands between him and any large achievement is his deeply rooted, unappeasable need to look longingly backward, an impulse that goes beyond nostalgia.”

As if mere nostalgia wouldn’t have been bad enough! But based on what we know about the ravages of industrialism, it’s unclear why an “unappeasable need” to look at what was lost is so objectionable. Many of the costs of progress that Tarkington tallied up have, at this point, mostly vanished from general awareness – it’s not such a bad thing to be reminded of them. And yes, perhaps the angst Tarkington surveyed was of the ordinary, not the high-modernist, sort, but it was still a fit topic for exploration.

In any case, Gottlieb’s dismissal followed Thomas Mallon’s only slightly more favorable assessment in a 2004 Atlantic monthly article.

“The vast body of his mediocre work has so suffocated the fine (The Magnificent Ambersons) and the small bit of great (Alice Adams) that one decides to go back to Tarkington out of a curiosity both literary and sociological: how does such a ubiquitous and, for a time, honored figure disappear so quickly and completely?”

Mallon musters no less an authority than F. Scott Fitzgerald to put the Hoosier down, saying Fitzgerald had Tarkington in mind when he expressed his fear of lapsing into a condition that would render him uninterested in anything but “colored people, children, and dogs.”

At least Gottlieb and Mallon, those 21st century literary heavyweights, saw fit to write about the forgotten author at all. A 2024 search of the Jstor database of scholarly journals finds no full academic articles in the current century and just one brief review (of the 2003 reissues of The Turmoil and Penrod). Otherwise, the man mostly turns up as a reference in lists of literary names being cited in support of some point or other.

Even Tarkington’s grandniece wrote in her otherwise loving 1983 memoir, “My Amiable Uncle,” that “he was a greater man than writer.”

The great man was prolific, however – something like 40 novels, 16 plays, many short stories — so there is a lot of material that could be rescued from obscurity if one believes that even if a better man, he was a good enough writer.