Book Review: The Air Loom and Other Dangerous Influencing Machines, by Thomas Röske, Bettina Brand-Claussen and others. Catalog by the Prinzhorn Collection, 256 pages, 92 illustrations, 2006. ISBN: 3-88423-237-1.

This book, also a catalog for an exhibit at the Prinzhorn Collection, is even more focused on psychiatric issues than the Collecting Madness volume.

This book, also a catalog for an exhibit at the Prinzhorn Collection, is even more focused on psychiatric issues than the Collecting Madness volume.

In an earlier time that could have been problematic, but the success of Dubuffet and his followers in liberating the art from its psychiatric context actually makes it easier to appreciate the insights. Although there is still plenty to debate relating to terminology and the significance of biography, the specifically medical terrain no longer feels like an impediment to aesthetic value.

In this case the medical context is a useful reminder of the pain often associated with these creative exercises, but it also underscores how these works constitute portals into other worlds, albeit wholly interior ones. Fuller understanding of their delusional background makes it even more engrossing to enter these bizarre and distorted worldviews.

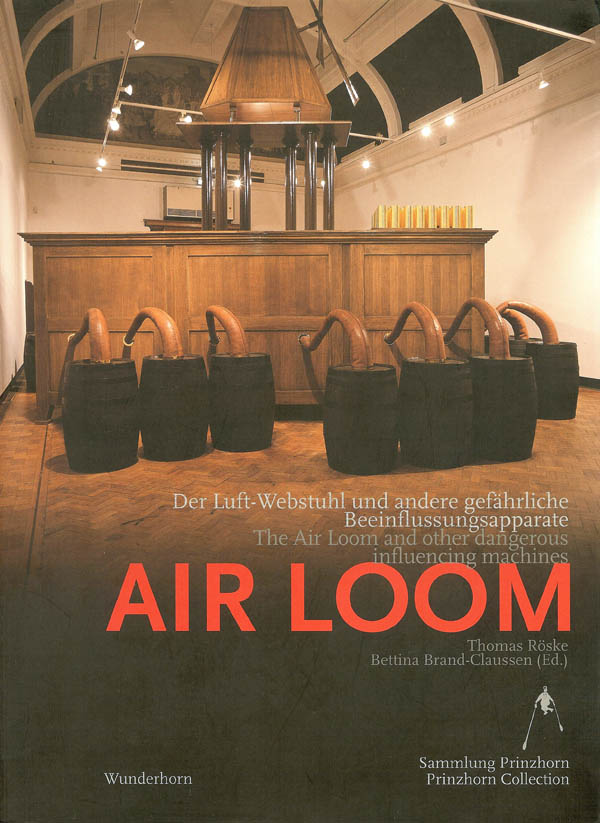

The historical and sociological meaning of these materials also adds to their impact. Röske and Brand- Claussen point out that James Tilly Matthews’ schematic representation of the Air Loom — a pneumatic machine that he believed pumped out vapors to control his behavior — constitutes the first documented concept of a mind-control device. Remember that in 1800 the industrial revolution was still in process and the idea of all-powerful machinery was in some ways still novel. What is now a common enough trope in literature, movies and cartoons — equipment that can control a person’s behavior and thoughts — originated in the delusions of paranoid schizophrenics.

Indeed, other more recent fantasies of influencing machines (a psychiatric term for mind-control devices) bring the psychotic and the scientific even closer together. As essayist Verena Kuni points out, in the early years of radio the notion of similarities between radio and brainwaves interested scientists as well as asylum inmates, with experiments attempting to validate whether the brain could be influenced by radio waves. Of course, in our day the notion of direct interfaces between electronic devices (e.g., computers) and brains is no longer relegated to the far side of visionary.

Meanwhile, much of the art shown here is magnificent, though as in Collecting Madness the illustrations are not profuse. The drawings of Joseph Schneller and Robert Gie, not to mention the embroidery of Johanna Natalie Wintsch, are truly art brut masterworks and are well reproduced.

Unfortunately, neither of these books is easy to come by, at least in the United State. You will need to find a European seller online and take the hit on both the exchange rate and the shipping. But they’re both still a bargain compared to two volumes specific to the actual Prinzhorn collection that were published in the U.S. — Beyond Reason, catalog to a traveling exhibit of work from the collection, and Artistry of the Mentally Ill, Prinzhorn’s own monograph. Even in paperback, you will be hard-pressed to find either of these important books for less than $100.