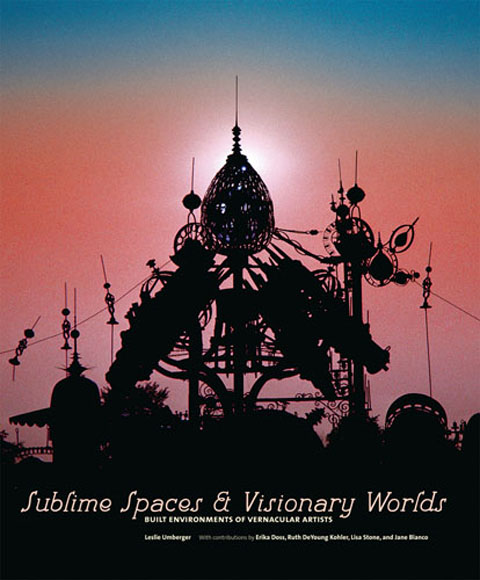

Sublime Spaces And Visionary Worlds: Built Environments Of Vernacular Artists, By Leslie Umberger, Erika Doss, Lisa Stone, Jane Bianco and Ruth Kohler. Princeton Architectural Press, 424 pages, 650 color plates and 100 black and white illustrations, 2007. ISBN 1-56898-728-5

This is a blockbuster catalog for a blockbuster show, and perhaps the best book yet published on the subject of art environments.

The structure is conventional—a handful of essays bookend a set of illustrated biographical vignettes (22 in this case, with exceptionally rich photo reproduction). But intelligence and serious intent distinguish this effort from the usual run of coffee table books. The straightforward biography focuses on understanding how the environments and their artists developed, which is especially relevant in a context where the work’s physical evolution illuminates both its meaning and its current state of being. This is a non-incidental consideration for nearly every one of these sites, given their exposure to the elements and to a sometimes-hostile populace.

Leslie Umberger, who curated the show at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, and wrote most of the book, shows unusual, and admirable, caution in accounting for the work of self-taught artists. Most refreshing is the absence of the sentimentality that too often substitutes for analysis when people are confronted with astonishing exercises in creativity. Her biographical sketches are carefully sourced and free of the undocumented, frequently far-fetched and self-serving anecdotes that all too easily fill the many gaps in our actual knowledge of these artists’ lives and works. (People, artists or otherwise, are not necessarily reliable in their accounts of their own history or the interpretations they apply to it.)

Umberger also avoids sloppy inferences from the facts that we do know. Her account of David Butler, for example, recognizes his religious convictions but avoids jumping to the conclusion that religion was the fundamental motivation behind the painted metal constructions he placed around his Louisiana home. “Butler never claimed that God put these dream visions into his head, although he did believe that he received a divine gift that allowed him to transform his dreams into sculptural forms,” she writes.

If not a strictly classic example of religious motivation, Butler is a case study in how environmental work by self-taught artists can go awry. Popularity can play out tragically when it descends on people who don’t necessarily want it and are ill-prepared to face it. Butler was unable to accommodate the many people who craved examples of his deeply personal work other than by stripping bare the environment that brought him to public attention in the first place.

Of course, overfeeding is only one peril. The chapter on Milwaukee’s Eugene Von Bruenchenhein highlights the opposite problem: unrequited genius.

“Who can fathom what has been stored up in only one brain?” asked Von Bruenchenhein, as prolific in his writings as he was in his art and acutely aware of his own creative isolation. “The real artist, one who comes from nothing like I did, with no art schooling necessary, has to live in two worlds. I have to remain on my side of life while the great majority live on their side. When they ask, how did you come by all the things you paint and form in clay, and since there is no answer for such things, I just have to live in my own little world.”

That very few people were in a position to even ask that question until after his death is a not-unusual art brut phenomenon. But in his awareness of mainstream art, Von Bruenchenhein did not conform to the paradigm, and he was acutely conscious of himself as an artist. This was not art that did not know its name. Yet he shared with the more pure among artists brut the fact that raw talent and drive transformed his labors into an artistic intensity that overshadowed training and recognition. If Von Bruenchenhein’s belief in his own genius was entirely justified, one still wonders how his immense creativity would have developed had it interacted more with others.

The kind of neglect Von Bruenchenhein suffered in his lifetime could extend for decades after the death of the environment builder. Some works simply disappear. Others, like E.T. Wickham’s statues on a country road in north central Tennessee, are vandalized beyond repair. While Sublime Spaces has several examples of environmental work treasured and cared for right up through a formal preservation process, it documents a number of recovery stories where only through heroic measures was an artist’s work, or even a portion of it, rescued.

A remarkable number of these stories have involved the Kohler Arts Center and the Kohler Foundation (of toilet fame). Their unique partnership in preserving and presenting environmental art reflects their home state’s tradition of outdoor artistry, but also Ruth DeYoung Kohler’s leadership. Her introductory essay recounts how she became interested in this work, and gives the inside story behind the pioneering preservation of Fred Smith’s Wisconsin Concrete Park in Phillips.

Lisa Stone’s closing essay also takes the reader behind the scenes, laying out some of the philosophical premises behind the preservations detailed in the book as well as offering something of a how-to guide. She adds some additional small but fascinating details of what can emerge in the course of these projects, such as the fragments of Carl Peterson’s sculptures that were dug up from his yard years after the environment was dismantled and the property passed into other hands.

Fortunately, the Kohler Foundation got control of Mary Nohl’s house and work before neglect, or worse, could take its toll. The environment had provoked a certain level of hostility in her North Shore Milwaukee community, where her lakefront property was widely known as the “Witch’s House.”

Nohl’s good-natured art hardly deserved such a response, though it did embody a strong individualism as well as wide-ranging artistic interests. Nohl, who studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, invested a sophisticated level of craft in her work, especially the jewelry and other smaller items that filled her house’s interior. But her yard environment was an over-the-top display more commonly associated with self-taught creativity than with academic training. Even if the outdoor sculptures were individually innocuous, together they reflected a to-hell-with-the-neighbors individuality characteristic of outsider environments.

As Umberger points out in her opening essay, self-taught environment builders typically intertwine home and art so deeply that they cannot be disentangled, whereas professional installation artists usually operate in a space quite apart from their home life, and at a much higher level of abstraction. That may be why Nohl seems to have more in common with Fred Smith than with artists who share her academic background, while Nek Chand, whose biography places him clearly in the self-taught camp, created a site that resonates far more than Nohl’s with the installation projects of trained artists. That’s not a negative by any means—Chand’s Rock Garden of Chandigarh (sampled in the book and show) is one of the world’s great environments—but the fact that it was built away from his home seems to have made a difference in the feeling it projects. Perhaps its separateness makes it seem more calculated. What Randall Morris calls “homeground” could represent a stronger artistic force than the distinctions usually attributed to training and biography.

Meanwhile, Emery Blagdon’s achievement stays more comfortably within outsider conventions, solidly rooted in homeground. He was untrained in art, isolated in his rural Nebraska home, personally eccentric and, most important, the creator of stunningly innovative, delicate and beautiful work. As one admirer said of his environment, housed in an out building: “Outside there are miles and miles of nothing but Sandhills, a few cornfields, a few cattle, otherwise, absolutely nothing—and here [was] this whole world contained within the shed.”

Meanwhile, Emery Blagdon’s achievement stays more comfortably within outsider conventions, solidly rooted in homeground. He was untrained in art, isolated in his rural Nebraska home, personally eccentric and, most important, the creator of stunningly innovative, delicate and beautiful work. As one admirer said of his environment, housed in an out building: “Outside there are miles and miles of nothing but Sandhills, a few cornfields, a few cattle, otherwise, absolutely nothing—and here [was] this whole world contained within the shed.”

The life story Umberger outlines is a necessity for grasping Blagdon’s art, which is nigh incomprehensible if you don’t know he was attempting to create machines for physical healing. The story not only helps explain the objects, it also deepens the paradox embedded in them. You can sense the beauty coming into existence as he created his elaborate found-object sculptures and abstract paintings. Yet he undercut that beauty almost immediately, stacking the paintings one atop the other or laying them face down on the ground. There was apparently no dilemma for Blagdon, since these were created to be part of a healing machine rather than as subjects of aesthetic contemplation. But do Blagdon’s intentions set the limits for how we appreciate his work? In fact, to uncover an aesthetic achievement that is alien to those intentions we have to literally set them aside.

In any event, the chapter on Blagdon whets the appetite for a more comprehensive publication on the artist, indeed, for dedicated publications on other creators featured in this show as well, especially those whose art is no longer accessible in situ. A full account of Von Bruenchenhein’s home or Mary Nohl’s would be enormously satisfying.

In this regard, it’s a little disappointing that a number of important sites did not qualify for the catalog’s lavish treatment. One imagines that places like Eddie Owens Martin’s Pasaquan and Howard Finster’s Paradise Gardens are missing because neither Kohler organization has engaged with them. It’s just a shame that even the Kohler Foundation isn’t rich enough to apply its loving kindness to everything artistic.

Do you have an email mailing list? If so, I would love to be on it. I’ve been reading lots of your articles and can’t get enpough of what you have to say and show me! Thank you! Cynthia Weston