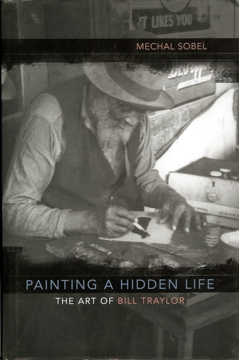

Painting a Hidden Life: The Art of Bill Traylor, by Mechal Sobel. LSU Press, 256 pages, 46 illustrations, 2009. ISBN 978-0-8071-3401-6

Pity the poor dead outsider artist. Odds are good you’ve been reduced to a collection of anecdotes gathered by an early collector or dealer then recycled, with declining fidelity, through biographical capsules, reviews and newspaper articles. Your life is a series of clichés attached to a stunning body of work.

If you’re exceptionally lucky, like Martin Ramirez, you may eventually pique the interest of serious scholars and become the subject of actual biography. But when your life story is a matter of luck, it can go either way. Witness Bill Traylor, an artist on par with Ramirez in importance and depth, but a test case for a different treatment, a genre that might be labeled “speculative biography.”

The recipe is:

Betty M. Kuyk applied an overlay of African cultural influence to Traylor’s life and work in her 2003 study, African Voices in the African American Heritage. Now Mechal Sobel builds on Kuyk’s work, which she glowingly cites, adding her own focus on the southern black conjure, or hoodoo, culture of mojo hands and spirit bottles.

While they’re at their main points, Sobel and Kuyk each offer tantalizing glimpses at Traylor’s actual life, starting as a slave in 1853 and ending in 1949 near the Montgomery, Alabama, streets where he lived and worked as an artist for several crucial years in the late 1930s and early 1940s. Sobel in particular combed census records, interviewed descendants and looked at other sources to gather as much fact as she could, and indeed overturns some accepted assumptions about Traylor’s life. However, the amount of available fact ultimately did not appear sufficient for her narrative purposes.

Like most of us, Sobel initially found Traylor’s art highly cryptic. But she argues that far from being mysterious, his conjure and African imagery told stories that were opaque to white people but perfectly clear to his intended black audience. Traylor was mounting an eloquent protest against the Jim Crow South in plain view without risking the punishment usually accorded to blacks who resisted the segregationist regime. Indeed, she finds his intentions so apparent that she takes to task Charles Shannon, the sympathetic (and, not incidentally, left-wing) artist who was Traylor’s patron and advocate for neglecting the work’s powerful social content.

It’s a thrilling notion. One wants to believe, with Sobel, that in some way Traylor’s art constituted street propaganda that helped pave the way for the Montgomery bus boycott. She brings her theories into the realm of possibility with her extensively footnoted research not only into Traylor’s own life — where there are some new facts to be known, if only a few — but also into the much more knowable history of his surrounding community and culture.

Like Kuyk and many other writers on art by southern blacks, Sobel sees powerful African influences at every opportunity, but her attention is really engaged by more immediate influences. She explores not only conjure and the blues, but also the life ways of Traylor’s time and place. For example, she points out that the common practice of using old newspapers as wallpaper enveloped poor southerners in graphical galleries, opening the possibility of such an influence on Traylor himself.

However, Sobel’s excitement at unlocking, or rather debunking, the mystery of Traylor’s art outruns the evidence, and she doesn’t slow down as her arguments become more and more circular: She hypothesizes that Traylor was exposed to conjure culture; she interprets any images that could relate to conjure as doing so; those same images demonstrate that conjure is represented in the art. QED. The loop tightens into the markedly speculative proposition that Traylor was not only familiar with conjure but was a practitioner.

Throughout the book, possible meanings seem to morph with inevitability into authoritative statements of intention and biographical fact. The appearance of triangles and squares, which happen to have special meaning for Masons, puts Traylor into a lodge. His use of common primary colors is freighted with hidden meaning because they have significance both in conjure and in African art. “Simple animals” aren’t just animals but spirit creatures — Haitian, African, anything other than what Traylor may have straightforwardly seen and wanted to represent.

It’s not that there are no deeper meanings there, and Sobel deserves credit for not throwing up her hands at the difficult task of unlocking them. Indeed, in some sense she rescues Traylor from overly innocent readings by recognizing the disturbing content in many of his drawings. His body of work represents more than an old man observing the passing parade, and Sobel’s expositions aren’t less reasonable than seeing nothing more than superficially simple animals and common colors.

But there is a discomfiting disparity between her aggressive interpretations and the extremely circumstantial evidence she uses to back them up. That disparity becomes especially acute as she connects specific drawings with the death of Traylor’s son Will at the hands of Birmingham, Alabama, police in 1929. Construing a pair of crucifixion drawings as lynching narratives makes for a compelling story, but it’s not clear that it does Traylor justice, either as a matter of history or aesthetics. It’s hard not to wonder whether Traylor, despite his humble origins, might have been after something more universal than strictly personal in at least some of his art.

Even when Sobel seems on the firmer ground of historical description she is still prone to slipping into heavy speculation. She is willing to accept as fact Betty Kuyk’s claim that Traylor killed a man, even though Kuyk’s evidence was decades-old, third-hand gossip related by the white owner of the funeral home where Traylor sometimes slept. Sobel goes even further, spinning a narrative that the murder involved the lover of Traylor’s first wife. There is no evidence for this claim at all, however, beyond Sobel’s own reading of imagery in selected drawings.

While any artwork is fair game for interpretation, and Traylor’s cryptic drawings fairly begs for it, one wonders if the lives of artists of more conventional stature — Picasso, say, or Pollack — could respectably serve as fodder for such loosely argued biography. Sobel’s book responds to the reasonable desire to replace the mystery of Traylor’s meaning and motivation with a fully conceived narrative. Believe it if you wish, just don’t confuse her ever more elaborate tale with actual history.

A version of this review originally appeared in Intuit’s Outsider magazine.

The reviewer naively assumes that any funeral home owner in Montgomery would be white, thus ignoring the copious evidence on p.167 in my work, cited above, that he was African American. The fact of the “murder” was reported to him by Traylor’s companion, who came from Traylor’s home community. A salient point in Traylor’s life is his baptism in the Roman Catholic faith shortly before he died.

Thanks for the comment. Indeed, nothing on that page of your book explicitly indicates the race of the funeral home owner. My dubious assumption.

I agree with the reviewer. There is so much wishful thinking and conjecture in this book. There is no way to know many things about Bill Traylor and his imagery. but making things up is irresponsible.