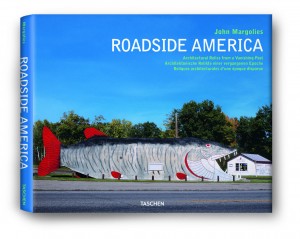

John Margolies, Roadside America, edited by Jim Heimann, with contributions by Phil Patton, C. Ford Peatross and photos by John Margolies. Taschen, 288 pages, about 400 color photos, 2010. ISBN: 978-3-8365-1173-5. Hard cover $39.99.

The enthusiasm for vernacular expression that began flowering in the United States in the 1970s never quite gelled into a unified movement. Yet a new generation did learn to value the work of self-taught artists and a sizable coterie of writers, photographers, architects and others discovered an exterior landscape whose aesthetic dimension was almost entirely accidental, but all the more striking for it.

This was the American roadside, most prominently the two-lane highways that dominated long-distance travel in the Mid-Century period but also a vast array of mostly commercial architecture and signage. This could range from almost anything in neon to the eccentric duck-shaped building on Long Island celebrated by architects Robert Venturi, Steven Izenour and Denise Scott Brown in their ground-breaking book, “ Learning from Las Vegas: the Forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form.”

If early lovers of what some were then calling “contemporary American folk art” felt no love from an art establishment that had little use for the work of self- artists, how much worse the estrangement of those claiming to value the epitome of American ugliness? Not only were they going up against the modernist revulsion expressed so well in architect Peter Blake’s influential book “God’s Own Junkyard,” they also were taking on a decade of highway beautification launched by the former first lady of the United States, Lady Bird Johnson.

Yet Venturi’s early dissent gained increasing support into the 1980s with an outpouring of work that brought attention and appreciation to roadside architecture. There was urgency from the realization that this landscape was in the act of vanishing, victim to the elements as much as to changing fashion and economics. Generational change was also at work as post-modernism emerged to contest modernist views of what constituted embarrassing junk.

As Phil Patton’s introduction to “John Margolies, Roadside America” points out, love of this stuff was not entirely new, most notably anticipated in Walker Evans’ many photos of mundane signs and commercial buildings. It took decades before Evans’ taste was vindicated, though, a process that started in earnest with John Baeder’s photorealistic diner paintings (published in 1978 as “Diners”) as well as Charles Jencks’ tribute to eccentric tract homes, also 1978, “Daydream Houses of Los Angeles.” That was only a year after Venturi’s book and a year after Jane and Michael Stern’s “Roadfood” began their long-term tribute to the vernacular food those diners served. Meanwhile, fast food architecture got its due the next year with “White Towers,” by Paul Hirshorn and Steven Izenour (turning up again) and 1979’s “American Diner” by Richard J.S. Gutman and Elliott Kaufman.

1981 brought “California Crazy” by Jim Heimann — and the ground-breaking survey by perhaps the greatest exponent of roadside art, John Margolies, with “The End of the Road: Vanishing Highway Architecture in America.”

The books by Heimann and Margolies were both modest paperbacks, their formats too small to do justice to their photographic content. Margolies’ was a mere 94 pages, but there were many more volumes to come from this prolific hunter and gatherer of roadside images. The new “John Margolies, Roadside America” is a fantastic summing up of 30 years of labor.

His aesthetic clarity contrasts with the thread of roadside mania that most fully entered mainstream culture — a nostalgia-fueled appreciation of Route 66 and other tourist highways that resonate with the childhood memories of Baby Boomers. The old highways movement is possessed of its own charm and has helped turn up lots of great places. But it tends to be more about recapturing a feeling than about art or artists.

Margolies can also be distinguished from the post-modernist fascination with decoding a world of signs and symbols formerly treated as opaque cultural noise. A scholarly work like Karal Ann Marling’s 1984 “The Colossus of Roads: Myth and Symbol along the America Highway” has, like many of the old-highway books, its own virtues. Margolies tends to focus on what the material can say for itself, with neither nostalgia nor academic overlay.

What comes through powerfully in every image is an intelligent, sensitive appreciation for the creativity of ordinary people and a passion that connects to the concurrent resurgence of interest in vernacular art, whether defined as “contemporary American folk” or “outsider.” In both cases you see a fanatical search for artistic expression rarely recognized (even by its makers) as artistic or even expressive. And if appreciation of self-taught art uncovers the creativity of thousands of talents whose efforts would otherwise be invisible, recognition of the art in America’s roadside vernacular can transform the commercial landscape from a dreary vista of self-serving signage into something that is endlessly fascinating in its aesthetic and cultural dimensions.

Margolies traveled the country from at least 1975 collecting images of roadside art the way others trolled flea markets and back roads looking for folk artists. His eye for the unusual and interesting is fantastic, whether it be hand-built mini golf courses, pig-shaped barbeque stands, giant fish or storefronts saturated with hand-lettered slogans.

His photography always favors the subject, taking great pains to exclude distraction. You will not see a person or a car in his work (unless, that is, it’s a picture of the lamented spindle of cars from Berwyn, Illinois, or similar subjects). That’s not to say he excludes context. Adjacent landscape, be it natural or commercial, typically has a strong presence.

Sentimentality does not. Aware as he is that his material is fast disappearing, his photographic approach is never overwrought. He favors straight-on views, letting the native richness in his subjects’ colors and content tell their own story.

The latest edition of Margolies’ work, from art publisher Taschen, does justice to his photos while offering an informative introduction by Patton, himself a contributor to the old highway renaissance with his 1986 book “Open Road: Celebration of the American Highway.” Patton traces interest in the commercial landscape back from the 1970s to Evans and other photographers of the Depression era. It’s interesting to see that this kind of material appealed not only to Evans but also to Edward Weston and Dorothea Lange, although even Evans’ enthusiasm pales in comparison with Margolies’ all-consuming commitment.

This review originally appeared in The Outsider, magazine of Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art.

Thanks for the thoughtful piece !