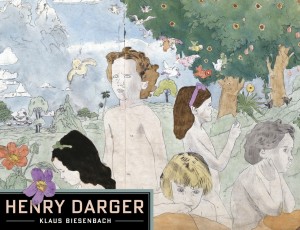

Henry Darger, by Klaus Biesenbach, with contributions by Brooke Davis Anderson and Michael Bonesteel. Prestel USA, 304 pages, 250 color illustrations, 2009. ISBN 978-3-7913-4210-8. Hard cover $85

This is the finest edition yet of Henry Darger’s artwork, with an extensive and beautiful selection of plates that includes a number of extra-wide foldout pages. It includes some of the goriest, most disturbing Darger images yet published but also pictures that demonstrate a totally different richness of imagination, such as his over-the-top facility with flowers.

Too bad the book begins bogged down in pointless argumentation about how to classify Darger as an artist. It’s a highly consequential question for author Klaus Biesenbach, who appears to believe that Darger’s accepted status as an exemplar of art brut genius actually undermines his artistic credentials. Biesenbach, chief curator of media and performance art at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, generously demurs that he is “not going to attempt to prove that [Darger] was not” an outsider. That disclaimer is contradicted, however, by his singular focus on proving that Darger was a real artist by demonstrating his similarities to (non-outsider) artists whose status is presumably uncontroversial. It’s odd and anachronistic to begin a major book on a major artist by rehashing tired concepts that lost their usefulness and interest long ago.

Biesenbach seems impervious to any lessons from the outsider art field, if not to its worst clichés and straw men — most notably the notion that outsiders by definition create in total isolation. Biesenbach says Darger was not a true outsider because he was — and this is a shocker — influenced by popular culture. In reality that proposition is irrelevant not only to Darger but also to the artists in any art brut canon you care to name, Adolph Wolfli and Martin Ramirez among them. The concept of pure isolation was put to rest a long time ago. To say that outsider artists are uninfluenced by culture is coherent only if taken to mean that they work independent of art-world culture, not the world as a whole. To use Jean Dubuffet’s framework, they create outside High Culture with a capital “c.”

If Biesenbach ignored Darger’s outsider status and simply compared and contrasted his work with other art there would be less cause for objection. Just because you or I happen to care about outsider art (or an equivalent label) doesn’t mean everyone should. The art should and can stand apart from the artist’s history. But Biesenbach appears to think that outsider status matters a great deal, in a negative sense: People in this class produce little of artistic value. So he tries hard – too hard — to find work by contemporary artists that has something in common with Darger’s, whether that’s violence, weird little girls, or cartoonish imagery. Few of these associations have enough depth to really connect, but for him they establish Darger’s artistic bonafides.

This legitimation by analogy is not very complimentary. Worse is the attribution of disreputable conduct, an effort that ironically is a direct function of the outsiderness that Biesenbach is taking such pains to refute on an artistic level. As someone notably eccentric in his personality and art, and virtually unknown in his lifetime, Darger is a tempting target, and not just for Biesenbach. But at least John MacGregor, who inched very close to labeling Darger a murderer in his exhaustive study “Henry Darger In the Realms of the Unreal,” had spent years researching the man and his work.

MacGregor’s implication that Darger was obsessed with missing children because he might have been responsible for one or more of their disappearances was purely speculative. Biesenback’s rationale for theorizing that pornography was one of the important popular culture influences on Darger is even thinner. His confusion of the classically melodramatic theme of lovely little girls in peril with pornographic iconography is dubious to say the least.

A similar degree of mix-up can be seen in the parallels Biesenbach draws with Joseph Cornell, which are not only superficial but also disingenuous. Cornell unequivocally belonged to the art world milieu. Darger unequivocally did not. That put them worlds apart even if Cornell was also an obsessive, eccentric, auto-didact.

If you bring biographical details into the picture at all, you need to account for the artists’ intentions lest you build your premises entirely on superficial likes and unlikes. Although another person’s intentions cannot with confidence be fully known, they also cannot with wisdom be fully ignored. Between an artist’s work and statements and history, enough can usually be pieced together to understand something of his or her purposes. Given the extensive research that MacGregor, Michael Bonesteel and others have conducted it should not be difficult to understand what sets Darger apart from most of the artists discussed in this book.

Although there is undoubtedly prestige in having a foundational essay written by a MOMA curator, and bringing a fresh and sophisticated voice to the conversation should be promising, those calculations go badly awry — a major missed opportunity that mars an otherwise excellent book.

Brooke Anderson’s contribution is too brief to entirely compensate for the dead weight of the opening essay but is nonetheless very valuable. That comes as no surprise based on her reliably excellent work in many similar volumes. She brings fresh insights into Darger’s working methods while referencing his journal and other materials to elucidate his artistic influences. She points to evidence that those influences go beyond the popular culture sources usually cited and include works like the 15th century Ghent Altarpiece.

Such influences still don’t justify broad claims about whether Darger was or wasn’t an outsider. Familiarity with artistic images, whether their source is high art or low, is insufficient to defining someone as an artist brut. Anderson speaks to this directly in a footnote, arguing (with thorough justice) that even in Dubuffet’s original and aggressive definition these artists were not necessary isolated from culture as a whole but rather operating outside what he viewed as the debilitating context of the high-culture establishment.

The book concludes with 64 pages, reproduced in facsimile, from Darger’s autobiography. Darger makes pertinent allusions to his sense of having at least a theoretical audience, which in turn sheds light on his broader self image: “To make matters worse, now I’m an artist, been one for years, and cannot hardly stand on my feet, because of my knees, to paint on the top of the long pictures.”

Especially when compared with the thousands of pages of his “Realms of the Unreal” epic, the autobiography makes for easy reading while supplying new texture to his life. Although nothing except the most speculative interpretation supports the idea that Darger may have been a murderer or porn consumer, his own account establishes that he was guilty of arson at least once, and perhaps more than that.

The account also gives sense to his childhood nickname of “Crazy.” This man of excessive temper would have been hard to be with. Indeed, it was clearly hard for Darger to be with himself. It’s not such a leap to speculate that from his long struggle came the magnificent art that this book so powerfully reproduces.

This review originally appeared in The Outsider, magazine of Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art.