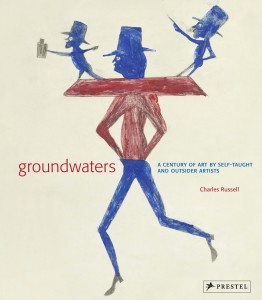

Groundwaters: A Century of Art by Self-Taught And Outsider Artists, Charles Russell, Prestel, 256 pages, 180 color illustrations, 2011. ISBN: 978-3-7913-4490-4. Hardcover $65.00

Charles Russell’s Groundwaters has the look and feel of a conventional coffee table book, and it can indeed be appreciated simply for its many beautiful plates representing the work of important self-taught artists of the 20th Century.

Start reading the text, however, and another kind of book emerges. Those pictures aren’t there just because they’re striking. Each one is referenced in the text to make or elucidate a point, and Russell has many to make. Their density results in a book that feels longer than its 240 pages, but it also enables Russell, professor emeritus of English and American Studies at Rutgers University, to provide succinct but thoughtful and thorough summaries of major themes and historical moments in self-taught art.

He starts with a review of the ground-breaking work of the two early 20th Century psychiatrists who effectively discovered “the art of the insane,” Walter Morganthaler and Hans Prinzhorn. That leads Russell to draw a useful contrast between the differing approaches to this work in Europe and the United States, with the first wave of European aficionados generally focused on the exceptionalism of self-taught artists while pioneering American advocates were more interested in connecting the creativity of the self taught with the native expressiveness of the “common man.” Those different perspectives, one rooted in the modern asylum and the other in 19th Century folk art, led to different ways of valuing the art and artists on the two continents.

Russell works hard to address some of the core definitional issues reflected in those differing views (and others) while avoiding the polemics that have so often arisen around matters of definition and delineation. Indeed, rather than bemoaning the term wars that swirl around labels like “outsider” and “folk,” the equanimious Russell gives all the many labels that have been applied, and often berated, their due as sources of meaning and insight.

“Art brut, folk, naïve, outsider, vernacular, visionary and so on … provide a larger sense of the breadth and variety of expressions of creative genius,” he writes. Elsewhere he unpacks some of the ideological blinders that have caused various terms, such as “naïve,” to go in and out of favor. There’s a lot to be said for his generous approach to naming conventions, considering that no there is no single term that can miraculously sum up this vastly varied body of work, and each term that’s been tried has, for all its faults, said something relevant and meaningful about the art.

The book is structured around individual artists, however, with x artists each getting chapters that conclude by referencing a handful of other artists with parallels in their work. Russell recounts each artist’s biography, but unusual for this genre he truly seems to do so only as needed to comprehend the art. In many cases the biographies mostly highlight how each artist engaged in a struggle to express themselves without access to the tools provided by academic training. Starting with Adolf Wolfli, the first artist profiled, we see how that struggle, combining with inherent genius, was embodied in the power and often the technique of the art, from Wolfi’s visionary density to the aspirational “super-realism” of artists like Morris Hirshfield and Drossos Skyllas.

Russell gives all his artists their due, as in this description of Martin Ramirez: “We sense the exuberance and self-assurance of the inventive and master craftsman, such that the visual order carries as much aesthetic and psychological significance as the work’s subject.”

Of course in Ramirez’s case that visual power for a time overshadowed subject matter that obviously tied the work back to Ramirez’s Mexican homeland. That obvious connection tended to be underplayed in favor of a focus on the artist’s mental state – a lack of balanced appreciation that Russell consistently avoids.

Most impressive, in fact, is his determination to tell the story of the art by unlocking the meaning of individual work, even that of the most eccentric and hermeneutical of artists. There is a deep respect for the artists in his view that their creations should be read as meaningful communications, not just aesthetic sports. His close readings clearly reflect a deep familiarity with the work as well as careful research.

“Encountering [August] Walla’s art we are again challenged, as with many outsider works, by the appeal of its visual immediacy and the insular, almost alien qualities of his personal vision,” Russell writes. But “amid the profusion of figures, words, and symbols in his densely packed compositions, Wall transmitted a vision of a world of profound meaning and inherent order.”

While the meanings we can grasp are necessarily not identical to what the work meant to the artists themselves, real connections are possible. Even with work that can be characterized as personal to the point of autistic, Russell finds resonances and meanings that are accessible and potentially important to those of us view it, beyond the formalist qualities of the work, which Russell also values.

He seems to throw up his hands only once when it comes to grasping an underlying meaning: What her cloth constructions may have meant to the profoundly disabled Judith Scott remains not just unknowable but unguessable. But even that uncertainty doesn’t prevent Scott’s creations from representing a rivulet combining into the vast stream of art, which is Russell’s fundamental premise. The fact that Scott’s motivations were certainly wholly alien to those of almost any other artist is just an example of the way in which outsider art, far from being a poor stepchild of the art world, benefits by what is in fact the infinitely wide frame of reference of its creators.

For those already familiar with that frame of reference this book is elucidating and thought-provoking. For those new to the field who aspire to deep engagement with the art from the get-go, it is the perfect introduction.

This review originally appeared in The Outsider, published by Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art.