Envisioning Howard Finster: The Religion and Art of a Stranger from Another World, by Norman J. Girardot, University of California Press, 304 pages, 16 color plates and 20 b/w illustrations, 2015. ISBN 978-0520261105. Paperback, $29.95

The prolific southern visionary Howard Finster was something of an enigma. How much of his colorful output was a matter of vision vs. showmanship? How important are his paintings vs. his Paradise Garden environment? Crazy, or crazy like a fox?

The flood of work (some 46,000 numbered pieces, nearly all with spiritual messages) and his loquacious sermonizing raise another key question: Are we obligated to take the religious content seriously? Does it mean anything at all, or is it just a marker of rustic authenticity, or perhaps proof of his charming eccentricity? If we do choose to grapple with the religious messages, how literally did he mean them, and what really was he saying? There is a strong dose of Christian evangelism in the Finster enterprise, but also pop-cultural and planetary references that are hardly orthodox, owing more to Finster’s own visions than to the Bible.

The flood of work (some 46,000 numbered pieces, nearly all with spiritual messages) and his loquacious sermonizing raise another key question: Are we obligated to take the religious content seriously? Does it mean anything at all, or is it just a marker of rustic authenticity, or perhaps proof of his charming eccentricity? If we do choose to grapple with the religious messages, how literally did he mean them, and what really was he saying? There is a strong dose of Christian evangelism in the Finster enterprise, but also pop-cultural and planetary references that are hardly orthodox, owing more to Finster’s own visions than to the Bible.

Fortunately, expert opinion is available. Norman Girardot, a longtime follower of Finster’s career, who happens to be a professor of comparative religion, shows in this book how Finster’s messages might fit into something resembling a comprehensible theology, and how that theology might fit into something resembling important art.

Despite Girardot’s self-confessed “penchant for interpretive hyperbole and textual prolixity” — visible here at times — the book gives the flavor of the particular religious environment from which Finster emerged and how he transformed it through his art.

“Finster, in his visionary and artistic expansion of the Southern Evangelical practice of preaching, moved in the direction of an increasingly aesthetic and unconventional affirmation of God’s divinity as revealed in diverse natural and human signs.

“The message to all of us — whether one is a literalist or a symbolist, a religious believer or a cultural aesthete — is that there is, or can be, some mythically imaginative dove or rainbow as signs in human life. No matter how jaded or disenchanted we may have become, a regenerative response to the human predicament is always possible.”

For Girardot, that is a fundamentally spiritual message that Finster made material.

“To really know the world we live in is finally to see through the passionate eyes of the artist and to know that our world is but an entangled composite of many worlds from the past, the present, and beyond,” he writes, citing the influence of folklorist Henry Glassie for this interpretation.

The appropriate response to that passion, at least when expressed in a masterpiece is, he says, a “totalizing experience” that corresponds to the total commitment to passion and process shown by the artist who made the artwork, in this case an artist who, in Girardot’s telling, was a man of actual visions.

Not everything Finster produced warrants that totalizing experience, as Girardot recognizes. The artist is notorious for having devolved into assembly-line reproduction, and for generally favoring quantity over quality as a mean of getting his message out. But Girardot makes a case for the man’s art, especially work from the 1970s and ’80s (not to mention the Paradise Garden environment, which even Finster skeptics tend to admire as a masterpiece in itself).

“The real excitement and interest evident in the early work is the manifest sense of intense, at times ecstatic, involvement in the process of creation and his inventive playing with plywood, mirrors, glass, plastic, metal, and other materials. We witness in this work the unfolding of his rapid, self-taught mastery of compositional form, brush technique, methods of coloration, figurative drafting, collage, foregrounding and layout, eidetic discovery, the filling of all available pictorial space, and overall decorative design.”

So if there is a coherent sensibility to this religion and evident passion in the best work, what are we to make of the artist himself? Finster was clearly driven to the point of weirdness, evident in both his work and in the kinds of personal encounters Giaradot describes in the book. And any self-proclaimed visionary puts himself somewhere that is not dead center on the sanity spectrum. But Finster was notoriously canny, and for his purposes fully functional in society. Yes, he had something of the egomaniac about him, but there are lots of megalomaniacs running around – most are not dangerous or psychotic, even if they can be oblivious to the social nuances around them and obsessive to the point of obnoxiousness. One of the strengths of this book is that Giaradot makes the question of diagnosis seem entirely unnecessary.

Of importance, and contrary to typical readings of the work, the only fundamentalism that Girardot recognizes in Finster is the artist’s own fundamental strangeness. But the shock of that strangeness was core to his liberating message. The different way of seeing the world that his vision demanded speaks to hope and acceptance, to a symbol-rich understanding of the world around us, physical and spiritual alike, rather than to a religious literalism.

“Visionary artists revive, reshape, and recycle the ordinary world by giving themselves and all of us access to other, more vibrant alternative realms…. These are worlds that, once entered into, can potentially shock us out of the stupor produced by the mundane world and open us to a more creatively eccentric, enduring, and full life.”

Indeed.

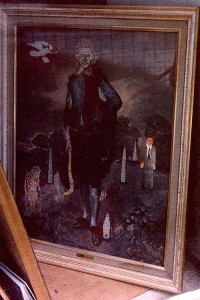

A personal note: Mid-book Girardot makes reference to me and my interestingideas.com web site. After a bit of flattery, he calls out the embarrassing fact that he was the creator of a piece (at left) I labeled “my all-time favorite Finster work.” Because I could only view it behind a window into Finster’s World’s Folk Art Church, I did not see Girardot’s signature. Still a great piece of art, and credit to Girardot for creating it.

A personal note: Mid-book Girardot makes reference to me and my interestingideas.com web site. After a bit of flattery, he calls out the embarrassing fact that he was the creator of a piece (at left) I labeled “my all-time favorite Finster work.” Because I could only view it behind a window into Finster’s World’s Folk Art Church, I did not see Girardot’s signature. Still a great piece of art, and credit to Girardot for creating it.

A version of this review originally appeared in The Outsider, published by Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art in Chicago

Excellent review of a book that’s really worth reading. Girardot’s placing of Finster in the context of his homeground and times is spot on. He also provides tools for some further thorough art historical analysis of Finster’s work.

Norman Giardot is the real deal. I did an interview with Norman several years back and we discussed this book before it actually came out. The interview took place in the Howard Finster Vision House the place where Howard lived when he had his actual vision from God to paint sacred art. Norman was kind enough to mention me in this book. I bought his book and I encourage you to see this interview to get an idea of how authentic Norman actually is. Thanks for being you Norman.

Chit Chat with David Leonardis

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gmSanoUWNXg part 1

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uygpiK9oRFs part 2