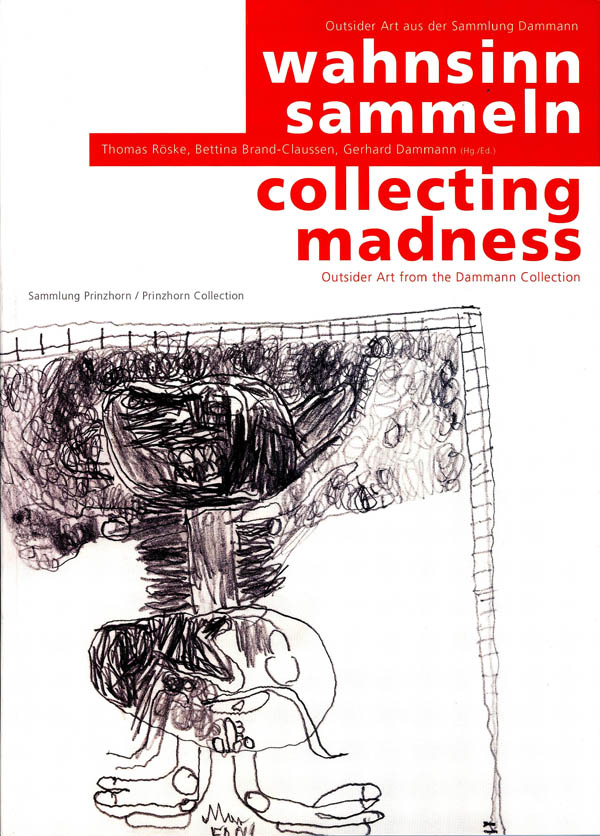

Collecting Madness: Outsider Art from the Dammann Collection, by Thomas Röske, Bettina Brand-Claussen, Gerhard Dammann and others. Catalog by the Prinzhorn Collection, 224 pages, 101 illustrations, 2006. ISBN: 3-88423-265-7

It may seem like a cheap shot to call this volume schizophrenic, but between its own punning title and its divided sense of purpose, the description is irresistible.

It may seem like a cheap shot to call this volume schizophrenic, but between its own punning title and its divided sense of purpose, the description is irresistible.

“Collecting Madness” refers both to the mania of acquisition and to a particular exhibit of a German collection focused on work by artists with histories of mental problems and confinement in asylums. The catalog itself is divided by an abrupt transition halfway through, switching from fascinating explorations of art collecting to a series of rather conventional considerations of specific art works and artists.

If the transition in the essays is a bit jarring, this is still that rare exhibition catalog where the writing is, on balance, more interesting than the illustrations, which are neither profuse and nor all that extraordinary.

The featured collection, belonging to Karin and Gerhard Dammann, does have strong work in it. The handful of exceptional pieces illustrated in the book include a 19th Century bed frame whose hand-carved faces exude a nightmare-inducing distress; a bit of fantastical heraldry from the 18th Century that demonstrates both expert knowledge of the craft and near paranoid fantasy; and a group of madonnas whose creepiness is capable of reducing children to tears, according to Karin Dammann. There also are some excellent examples of work from the House of Artists at the Gugging clinic, which all in all are less disturbing but very strong examples of asylum-made art.

Gugging, as Gerhard Dammann points out, “was a stroke of luck. The proportion of those who have genuine ability is just as low as in the population as a whole. The fact that someone is mentally ill does not make him an artist. In hospitals it’s always only one or two who produce anything remarkable,” he explains. Dammann is not so happy with how Gugging has developed, a sentiment he appears to share with others unhappy about the workshop’s increasing commercialization.

The Dammanns are fairly humble about their own collecting effort. They don’t aspire, to the epic scope of, say, the Lausanne collection de l’Art Brut or the ABCD Art Brut collection. The Dammanns do collect with serious purpose, though, and their exploration of the artistry of the mentally ill provides a strong jumping-off point for the authors. Even when one doesn’t fully agree with the point of view in any given essay, they are nearly all interesting and often provocative.

Some of the essays nicely turn the tables on the usual outsider art story line, with the collectors, rather than the artists, being given the psychoanalytic treatment. Thomas Röske, curator of the Prinzhorn Collection, considers the extremes of collecting — “narcissistic retreat from relationships,” isolation, pointless accumulation, addiction – while also considering milder instances of the habit. Among his conclusions: Collecting helps collectors construct their own identity. Those willing to incorporate outsider work into their identities set a positive example of inclusion for art that has been characterized by a long history of rejection and devaluation.

Bettina Brand-Claussen explores the early bits of that history, going back to the early 1800s, while also documenting the pre-history of the Prinzhorn collection (i.e., art-related activities at the Heidelberg Clinic before Dr. Prinzhorn took charge and assembled his historic collection of the art before it became brut). It’s clear that the relation between psychiatric and aesthetic appreciation of work by asylum dwellers was fraught from early on.

In his unsentimental view of the early years, Peter Gorsen demonstrates that conflict over terminology has bedeviled the field since its birth. Jean Dubuffet engaged in his own term wars as he tried to establish a non-psychiatric view of work that he was collecting mostly out of psychiatric institutions. “Art brut” the label was itself a weapon.