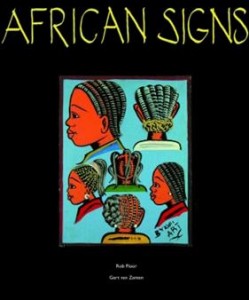

African Signs, by Rob Floor, Gert van Zanten andPaul Faber, KIT Publishers, 208 pages, 2010. ISBN 978-9-4602-2080-7. Soft cover $45

Every once in a while those of us who don’t often make it to Africa have an opportunity to glimpse the continent’s extraordinary commercial visual culture. As recently as this summer vibrant examples of hand-painted movie posters from the 1980s and ‘90s were on view at the Chicago Cultural Center, which also mounted a show in 1996 of elaborate decorated coffins from Ghana. Both genres have books devoted to the,

African hair salon and barber shop signs, meanwhile, were featured in an Intuit show in 1994 and have become what might be the most widely collected hand-made trade signs since those of 18th and 19th Century American came into vogue. These signs are popular enough that many of the examples that end up for sale abroad are apparently made specifically for export.

African Signs is a broad survey of Africa’s commercially inflected vernacular art. It collects hand-painted signs, mostly photographed in situ, across a number of categories, including food, clothing, health, electronics and the ubiquitous hair. Among other things, the book shows off a scale of work that can’t be grasped from the individual signs collected in the U.S. That scale includes many mural-size images, but also remarkable photo that shows more than a dozen individual signs displayed outside a pharmacy in Togo. And these being health signs, the explicit representation of ailments – some obvious and some obscure but many just gross — is easily as disturbing as the kitschy violence seen in the low-budget movie posters featured in the Extreme Canvas book and the Chicago Cultural Center show.

There is certainly a kitsch element contributing to the appeal of some of these signs, but only some. The degree of talent evident in them also varies, reflecting apparently low barriers to entry for the signs’ producers. As the introduction notes, the continent is generally too poor to produce the art school graduates who might otherwise populate a commercial art industry. But the need for commercial art in the continent’s thriving local markets has produced a demand for creativity that is ripe to be filled in interesting and creative ways.

Paul Faber, the museum curator who wrote the book’s introduction, tracked down one of these artists, who goes by the interesting name of “Middle Art.” Faber notes that Middle Art is one “of the hundreds of professional painters in Africa who don’t see themselves as ‘artists’ in the romantic sense … but as craftsman who make a living with paint and brushes. This modesty can also be found in the name ‘Middle Art.’ … He doesn’t consider himself very bad but also not very good, just Middle Art.”

However accurate Middle Art’s judgment of his own ability may, the talent displayed in this book is impressive if unpredictable. Some artists can’t manage much more than caricature, other produce nuanced portraits. Some show flights of imagination, others lavish loving attention on the most mundane (or sometimes bizarre) subjects.

This review originally appeared in The Outsider, magazine of Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art.