Unsealed: Bottle Cap Art | The Woolseys | The Patent Drawings | How To | The Race Question| The Blockbuster

The Galleries: Masterworks | Troops | Signed | Flashers | Other Shapes | Mine | Bottle Cap Inn | Two Monuments

A farm couple with a bottle-cap hoard and time on their hands sounds like the stuff of folk-art legend, and in Iowa’s Clarence and Grace Woolsey it was a pretty great one.

A farm couple with a bottle-cap hoard and time on their hands sounds like the stuff of folk-art legend, and in Iowa’s Clarence and Grace Woolsey it was a pretty great one.

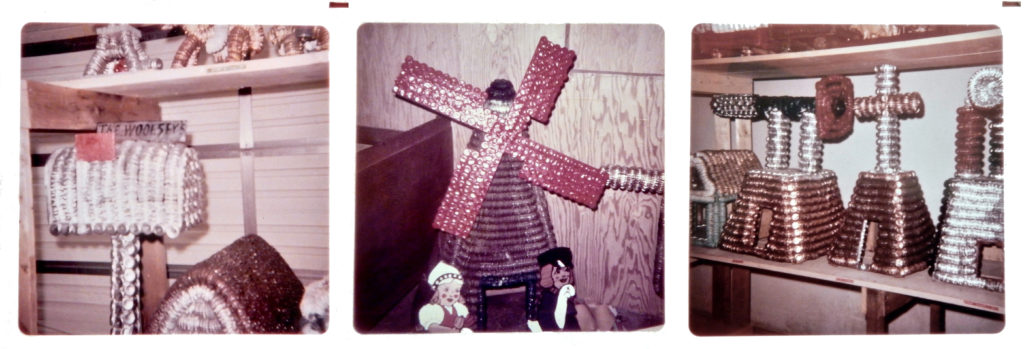

They sculpted hundreds of objects with bottle caps in the 1960s and early 1970s, and showed the work briefly before it vanished into the loft of a brother’s barn for more than 20 years. After the couple’s deaths, the sculpture hoard (including enough leftover caps to enable the creation of counterfeits using original materials) was sold at a farm auction in May 1993. Feeding the legend was the sale price – nearly the whole body of work brought less than $100 from a pair of bidders – and the market-making aftermath. The pieces passed rapidly through a chain of antique and art dealers until what started as a pastime, and initially looked like conventional Americana, came to the market branded as significant self-taught art. Individual pieces were selling for $5,000 or more within the year.

Iowa antique dealer Tom Van Deest estimated in 1994 that only seven Woolsey pieces were left in the state: “It came through and it just disappeared,” he said. “It was sucked out, like a vacuum cleaner went through.”

Van Deest was part of that chain of dealers who handled the Woolsey pieces, and his initial reaction to the work still resonates: “Little did I believe they would be of such scale, such detail and such imagination.”

In the Woolseys’ own time, what seemed to most interest the world was the huge number of bottle caps required to create the some 400 objects that newspaper articles reported in 1971. Volume was the primary theme of an article in the Waterloo Courier — one piece used 30,000 caps!

In fact, what to do with bottle caps used to be a topic of public concern, worthy of news coverage and advice. In World War II, metal shortages sent bottlers scrambling to collect old caps, and that attention continued in the years of increasing post- war abundance. In the absence of any kind of widespread recycling programs, people continued to accumulate bottle caps, and there was no end of ideas about what to do with the cork-lined metal disks.

Most solutions didn’t go much beyond the suggestions and instructions that appeared regularly in home craft publications, kids’ activity magazines and newspaper craft columns.

Picture frames, mud scrapers, table-top figures, baskets, trivets and other objects were all advised, and all produced in quantity by home crafters, as evidenced today by vintage merchandise sales on e- commerce sites like eBay and Etsy.

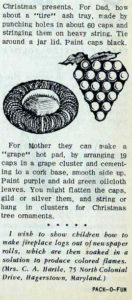

Grace Woolsey, according to her nephew Dale Price, was a hobbyist, and she almost certainly read some of those publications. “She’d kind of sit at the table and mess with things,” he said. Among other endeavors, she made little furniture out of old tin cans, a popular craft activity in the 1950s and 1960s. For at least one Halloween she made a group of scarecrows. There was also a wooden cut-out dear by her hand, and a peacock wall hanging. “Grace was always making something,” Price said.

That drive helped take Grace (1921–1992) and her husband Clarence (1929–1987) to a place beyond conventional handicrafts and hobby art – arguably to artistic mastery.

It seems that their intentions at the start were prosaic enough. They told the Waterloo Courier that one snowy night in 1961 they decided to figure out what to do with the caps they had collected, and they just started stringing them on wire. The paper reported that their first piece was a church, representational just like the wagons, barns, corn cribs, wishing wells, teepees and mailboxes they also went on to create. Their work in this vein is impressive enough, including one of their masterpieces: a life-sized, highly realistic bicycle.

Price tells a slightly different, and more intriguing, story. “She had those bottle caps and was thinking about what she could make of them.”

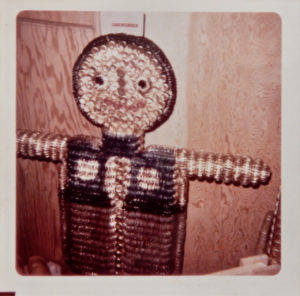

Grace “said she woke up one morning and said, ‘You know I dreamt I made something out of bottle caps.’ Clarence looked at her like she was crazy. She went ahead and took some bottle caps and baling wire. The first thing she made was a small stick figure of a person. She painted it with spray paint. It grew from there…. She talked Clarence into making other stuff.”

Clarence clearly came around. “Clarence had an idea and he knew it would be big some day,” Price said. “Clarence pretty much had the idea of what he wanted to do and how to do it.”

“I never imagined him having an imagination like that for him to think how to make bears or rabbits or aliens. His demeanor wasn’t like that. He was more serious or straightforward,” Price said. “Grace was more likely to think that way.”

Clarence did have a great sense of humor, Price’s wife Marcia said.

Clarence, a farm worker and former rodeo performer, designed and built the figures, Price recounted, with just a jigsaw – no power tools – in an old chicken house. Grace would decorate them with paint, glitter and other materials. A 1971 article in the Cedar Rapids Gazette also credited her with making some of the smaller parts using a pocket knife, and a young Price with helping.

“We had a two-foot by two-foot board. We’d lay all the bottle caps out. We had a little punch and a hammer and we’d punch a hole in each bottle cap,” he said, noting that Grace was particular about the hole being perfectly centered.

The bottle caps came from pop machines in stores around central Iowa, and the wood was from old fruit crates.

It appears that the medium – the thousands of bottle caps Price helped them collect and prepare – took hold of Clarence and Grace, and they were receptive enough to know what to do with it.

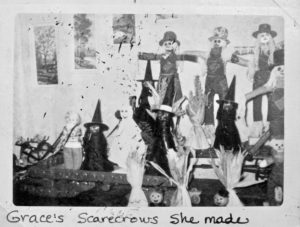

Bottle caps give a construction a unique texture and shape. Although a few bottle-cap objects, some of the Woolseys’ included, are quite large, even at modest size a monumental quality emerges when hundreds of the little metal disks are spread across a surface or strung on wire and twisted around. It’s visible in some of the best bottle-cap baskets made as handicrafts in the mid-20th century, in Miami’s cap-encrusted Bottle Cap Inn bar, and in some of the works of Mr. Imagination, among others.

With the Woolseys you can see it in their teepees and other structures, but their materials’ expressive potential finds its fullest representation in the dozens of figures they produced, typically around four feet tall, their basic shapes defined by strings of caps that wind around to create heads, torsos, legs, eyes and ears or antennae. Caps are nailed on flush to suggest faces and to cover feet. Popularly known to collectors as “bunnies” or “aliens,” these figures are actually too enigmatic for those labels. Clarence himself always called them “bears,” Price remembers.

The Crimped and Cutting Edge in Bottle-Cap Sculpture

The most common configuration of these figures sport twin protrusions from the head – call them bunny ears or alien antennae. But there is no telling exactly what the Woolseys intended. The figures aren’t even mentioned in contemporary newspaper stories, although the couple produced at least 100 of them. There is also not much rabbit-like other than those long, Bugs Bunny-style ears. Other figures have two or four small nubs around the head. Some are surmounted with various kinds of crests, or crests and nubs combined. None of them are typical representations of aliens.

All these features are made with tightly wound strings of bottle caps, which are both structural and decorative. In some cases, caps nailed flat to the heads form a face, though usually this layer just adds visible texture rather than actual features. Eyes, when present, were made with a ring of caps, sometimes with a single flat cap in the center. At times another single flat cap served as a nose. These faces are highly abstract. Grace’s painting, and the native color of the caps, mostly serve a decorative rather than figurative function.

Something aesthetically vital emerges in these figures – the materials speaking and the artists listening. Bottle caps are a low-resolution medium, with a certain level of abstraction required to solve any number of formal problems when sculpting them. Even representational objects can only go so far in suggesting the forms the maker is trying to depict. But the full impact of this creatively fertile constraint is visible in the Woolsey’s figures, whose archetypal quality repels quaintness and is an expressive step beyond farm-scene objects, wagons and windmills.

The Crimped and Cutting Edge in Bottle-Cap Sculpture

The point here isn’t, “How odd that these Iowa farmers stumbled into designs that look so visionary?” Yes, rural Iowa is not typically viewed as starting point for the creation of powerful art, though visitors to the West Bend Grotto of the Redemption might know otherwise. And yes, the Woolseys’ personal history is certainly interesting, and not irrelevant to the nature of their art. But none of that is as fascinating as the work itself. Their creative imagination, whatever its sources, took them to visually powerful destinations.

Although these figures are unique in the annals of bottle-cap art, and as bottle-cap art unique in the annals of art in general, it is still not hard to find work that resonates with them. They are totemic, relating them to some of the earliest known human sculptures – equally enigmatic and “low resolution” in their own way – as well as to the work of Woolsey contemporaries and more recent artists.

The most obvious parallels are Bugs Bunny – as iconic as any 20th-century artistic creation – or, more currently, Jeff Koons’ stainless steel rabbit. But those similarities are mostly about the ears. With their flat frontal stance and rigidly outstretched arms, the Woolsey figures – especially those with the crested headdresses – bring to mind other images, including pre-Columbian Mesoamerican imagery and Hopi Kachina dolls. More recent sculptures that resonate are the abstracted figures of modern artists like Joan Miró and Barbara Hepworth. Their sculptures are more abstract than the Woolsey pieces and often larger. But their iconic presence is not dissimilar.

Other parallels present themselves when thinking about the figures in quantity. Nek Chand’s troops of decorated concrete figures in his vast Indian environment come to mind, especially how bangles played a role for Chand similar to bottle caps for the Woolseys. Even the terracotta armies buried in Xi’an, China, echo with the Woolsey figures hidden in the loft of Grace’s brother’s barn in the years after her death.

The Woolseys’ development from representational and folky rural imagery to the monumental, totemic and semi-abstract is no easier to explain than the journey of any of these artists and craftspeople. The Clarence and Grace case is just as straightforward, and just as mysterious. Certainly there was something inherently obsessive about their project: Collecting and preparing tens of thousands of bottle caps is not a trivial accomplishment. Doing so at scale, producing 100-plus figures in addition to the hundreds of other objects, requires extraordinary determination.

Producing any great art requires no less commitment. Lest the Woolsey project seem like an eccentric and therefore isolating hobby, Price pointed out: “They had lived around there so long and so many years. They were just like normal people. They were good neighbors. If anybody needed something that they could make or wanted something done, they did it.”

Much of the work was produced at their home in Reinbeck, which lacked central heat and got really cold, he said. “They didn’t have anything. But they were always happy.”

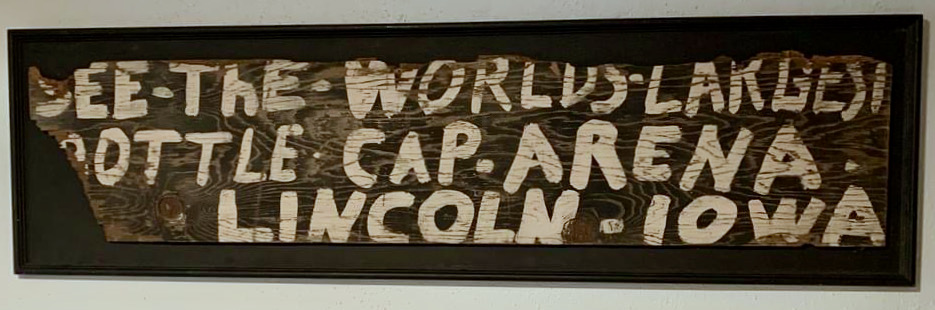

It appears that bottle caps for the Woolseys were a way to connect with their community. They required the help of their family and neighbors to gather the caps, and they shared their work with the public. The first time was a one-day exhibit in 1967 with an admission charge to benefit the “Crippled Children’s Fund.” The second, in 1971, was the couple’s “World’s Largest Pioneer Caparena,” in which they showed the material in volume over several months in a large building in Lincoln, Iowa, and charged admission (reportedly 25 cents).

Clarence hoped to create a real tourist attraction, Price said, who also noted that the name “Caparena” refers back to the 14 years Clarence spent in arenas on the rodeo circuit – Clarence claimed to have ridden in nearly every state, he said. (Clarence also was a cook in the army.)

Rather than selling pieces, the plan was to make a living showing them. Clarence became ill not long after the Caparena opened, however, and that plan was shelved. He died in 1987. Grace eventually retired to a trailer on her family’s Denver, Iowa, homeplace (which must have been large – she was one of 13 siblings) and died in 1992. The bottle-cap figures wound up in the barn.

Did Clarence and Grace think of themselves as artists, or, at least as artisans? Likely not so much. “They were just small country folks. Never would have thought of anything like” being artists, according to Price. But one suggestive reference can be found in the Cedar Rapids newspaper article: “Neither has had any art training, but Mrs. Woolsey said that she always wanted to take art.”

Woolsey family photos courtesy of Dale Price: Many thanks for generously sharing the photos and your memories.

This article was originally written in conjunction with “Caparena,” curated by David Syrek for Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art in Chicago. The exhibit included 12 dramatically lit figures and ran from January 1 to March 27, 2016. A version of this article also appeared in Raw Vision 92.

The 2016 Caparena exhibit installed at Intuit

Unsealed: Bottle Cap Art | The Woolseys | The Patent Drawings | The Race Question| The Blockbuster

The Galleries: Masterworks | Troops | Signed | Flashers | Other Shapes | Mine | Bottle Cap Inn | Two Monuments