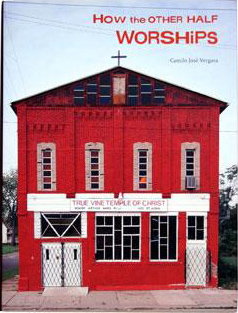

How the Other Half Worships, by Camilo Jose Vergara, Rutgers University Press, 286 pages, 2005. ISBN 978-0-8135-3682-8

How the Other Half Worships, by Camilo Jose Vergara, Rutgers University Press, 286 pages, 2005. ISBN 978-0-8135-3682-8

How The Other Half Worships celebrates one of the great engines of true vernacular expression – religion. The subject is inner-city churches, with an emphasis on the storefront variety.

Camilo Jose Vergara has spent years visiting and photographing urban churches and their people, fascinated by their architecture and decoration, by what people do in them and by what they do for people.

The book is built around his photographs, but it also gives the church folk a direct voice. The generous quotations from pastors and parishioners provide a good flavor for their religious language, although the book cries out for one of those supplemental audio CDs. The sounds of their services are a missing dimension.

By letting his subjects speak for themselves, Vergara is able to take everything here seriously without pretending that everything about these churches is equally serious. The oddball and the pathetic speak for themselves as eloquently as the serious and profound. To recognize one need not deny the other. But what can be said about contact paper stained glass, of which the book shows multiple examples? Are we obligated to respect it because the person who applied it takes what it decorates seriously? And if we are to respect the context, what does the serious use of kitsch tell us about that context? In the end, it is best to let the contact paper make its own statement, which Vergara does. The kitsch, it should be said, is not limited to make-do. Vergara also documents expensive efforts at religious grandeur that sometimes reflect just plain bad taste, even if they remind us that what looks now like ancient splendor was cheap ostentation in its own time. Excess assumes a very different aspect as the centuries pass.

In any case, the visual excess here pales besides the spiritual variety. The same passionate faith that finds religious resonance in stick-on stained glass has no problem detecting the miraculous wherever it can. The author clearly does not share his subjects’ precise belief in miracles, but he recognizes its power. Given the circumstances that many of these churches minister in, there’s great poignancy to that belief, at least from a skeptic’s perspective: If only the anointing that so many pastors claim really could accomplish the miraculous transformations they attempt to command.

What it does produce, however, is a great creativity whose truest expression is not so much in buildings or decoration but in the spiritual endeavors those buildings contain. As with so much outsider art, the ingenuity that is applied in the absence of conventional resources can lead to highly creative and idiosyncratic solutions, visible both in the way pastors struggle to bring order, solace and good works to their neighborhoods; and the way congregations work to create an empowered community of life-changing effect.

But if solving the spiritual problems of existence is the purest arena for expression in these places, it is not the only subject for this book. The aesthetic dimensions may be an ancillary benefit, thrown off by labors whose purpose is something else, but they are no less real or interesting.

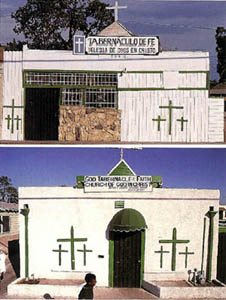

The disjunction between kitsch and spirit is itself a fascinating dynamic, but there are more straightforward cases of vernacular expression and self-taught artistic solutions on display. This eclectic culture not surprisingly reflects multiple wellsprings of expression. A pastor’s personal preference for green made for a nicely eccentric exterior at one church Vergara documents (first image below) while an uncorrected construction error accidentally (and interestingly) skewed the gothic echoes of an entrance at another (second image below).

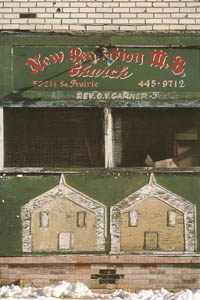

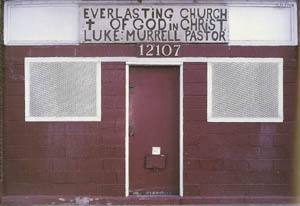

When congregations try to create a semblance of holiness by decorating storefronts that were designed for something completely different they often come up with architectural gems. Some churches try harder than others. Vergara shows one prosaic building with churchly window frames attached next to reliefs of holy swords and shields. Others show more secular indicators of aspiring respectability like fake stonework and wrought iron. Some churches settle for a basic entry and sign (often nicely hand-painted), and maybe a mural that captures the drama of sin and salvation. The murals range from the charmingly naive (second from bottom below) to examples of vernacular art that are powerful by any standard (third from bottom). Vergara’s artistic disimageies include John Downey, who made hellfire-and-brimstone images for a Los Angeles skid row mission in the late 1960s, with powerful paintings condemning alcohol and illustrating the beauty of a very art deco-ish heaven.

Whether in its aesthetic or spiritual practices, this community’s vernacular expression ultimately exudes the kind of authenticity that is often sought after in self-taught art but is in increasingly short supply as the field becomes thoroughly commercialized. There is no ambiguity about intention here and no risk of art world agendas. Not every material expression of these churches rises to the level of important art, nor is the important art they do produce the most important of their accomplishments. But still, it’s well worth looking at, and Vergara’s book is a great tool for doing so.

A version of this review originally appeared in Outsider magazine, published by the Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art.

All photos from How the Other Half Worships.

Read other outsider art reviews.