A photo gallery with fuller captions can be found at the bottom of this page.

Joe 40,000 Murphy was just a regular guy from Chicago’s Bridgeport neighborhood, but he lived his life as one long special event, building a private monument to it in his three-flat home on 34th Street near the heart of the working-class enclave’s old Lithuanian section.

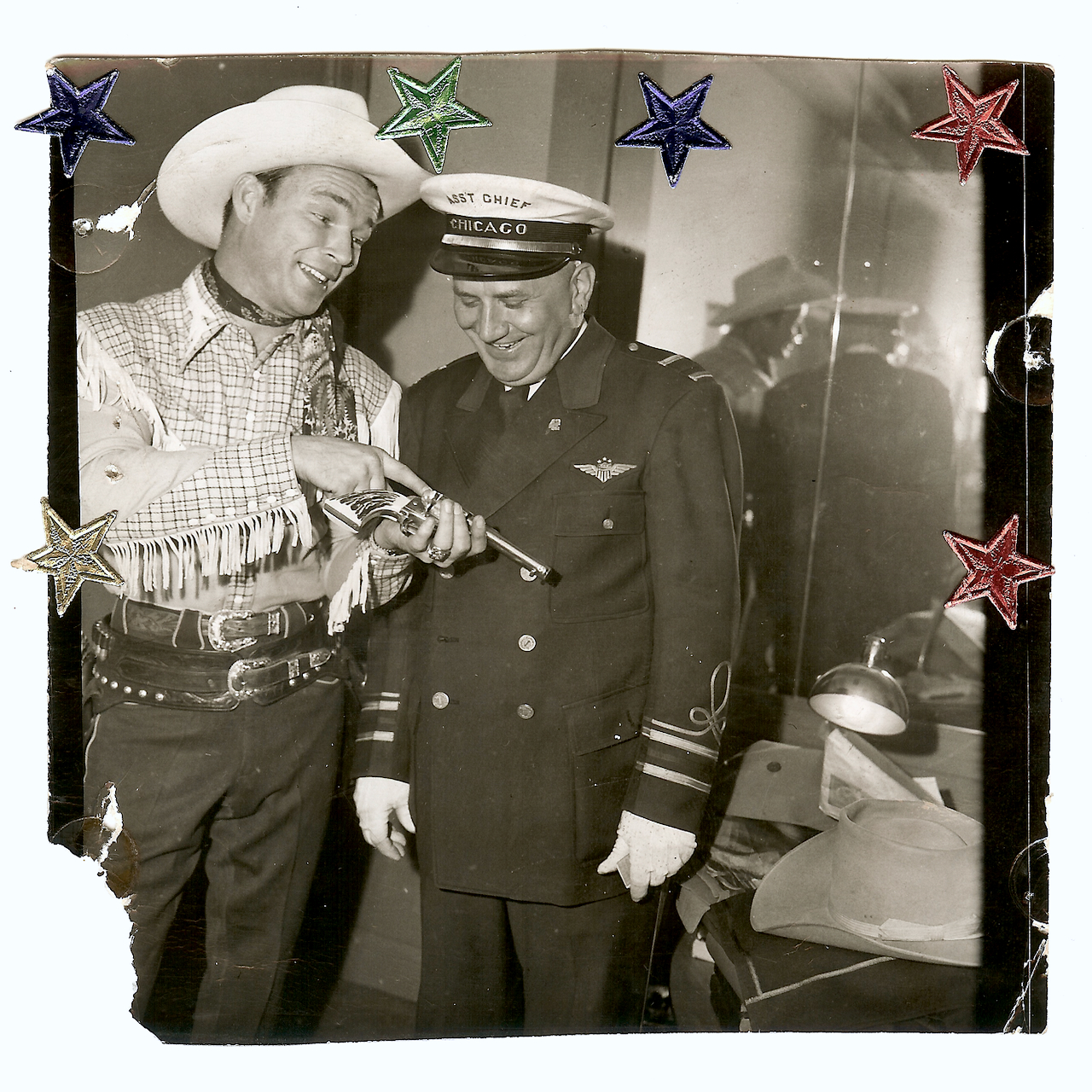

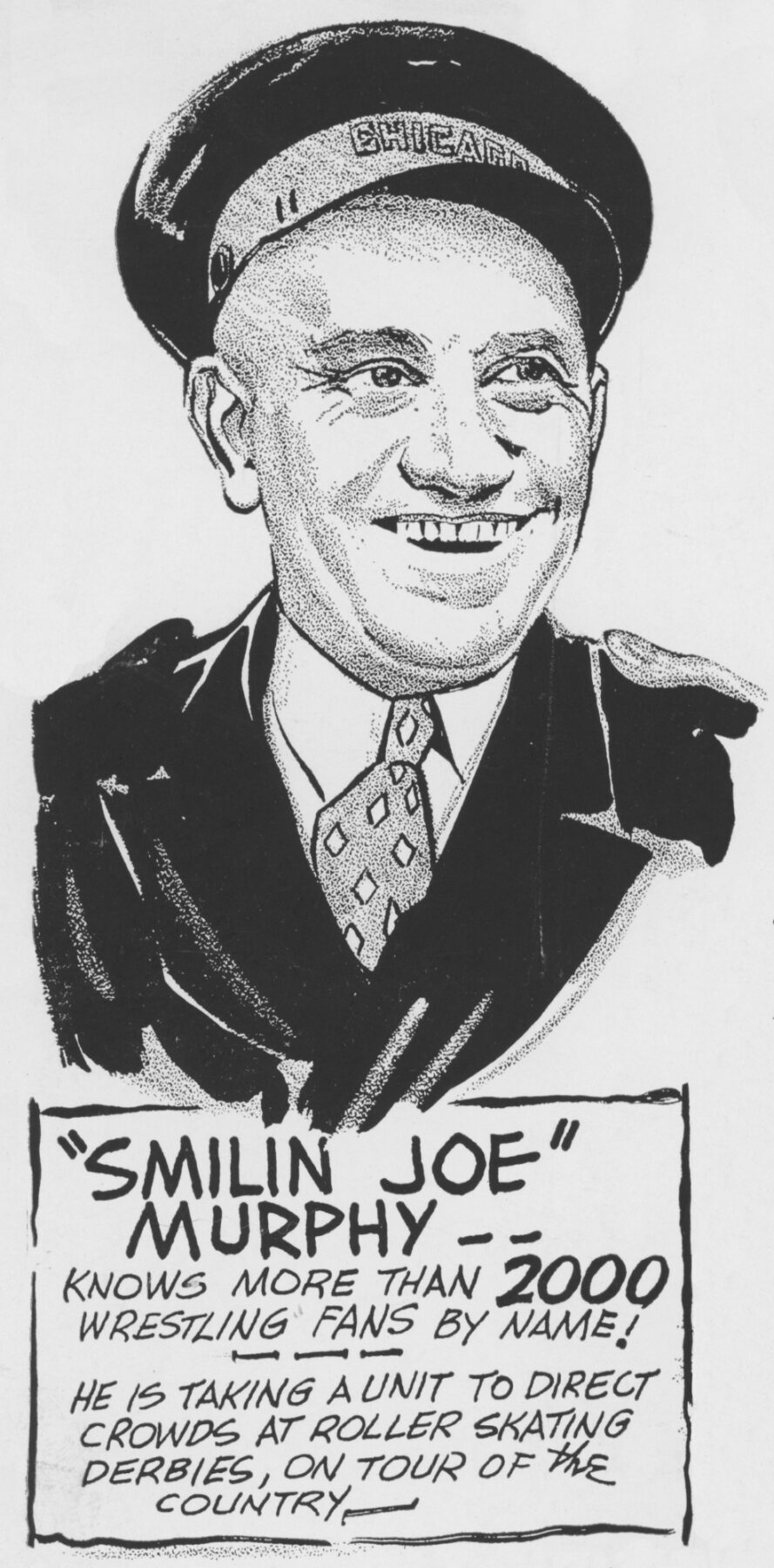

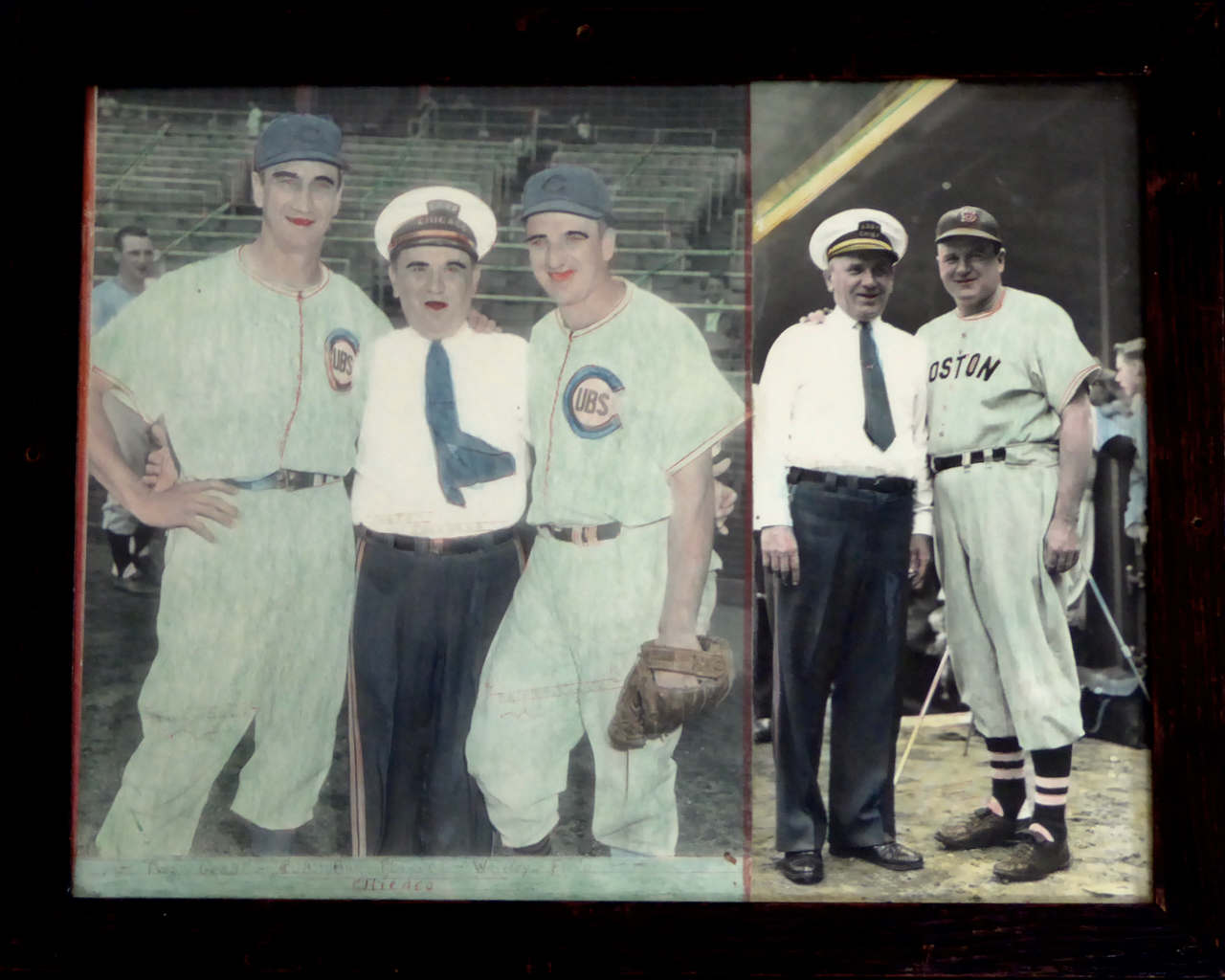

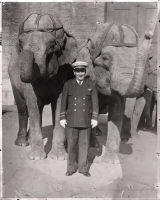

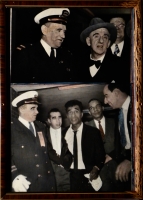

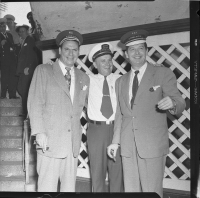

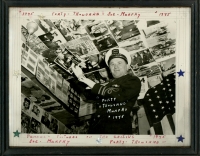

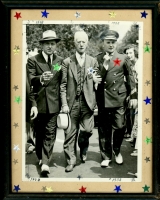

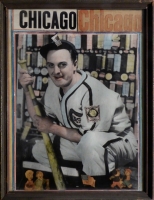

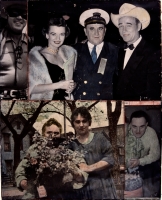

His enormous assemblage of photos, cartoons, admission tickets and other mid-century detritus added up to a spectacular art environment, though no one would have thought of it that way. The images he installed across the inside of his house and garage documented a fabulous world of banquets and braided uniforms, mink-clad actresses and showgirls in evening wear, ball players and professional wrestlers and elephants, with Sammy Davis, Jimmy Durante, Louis Armstrong, Joe E. Brown, Cary Grant, Harry Truman, Lawrence Welk, Dale Evans, Irv Kupcinet, Milton Berle, Bob Hope, Roy Rogers, Jayne Mansfield, William “Billy Goat” Sianis and a young Marilyn Monroe all passing through it (among many many others).

“Me, Murph, I knew ’em all. All the big shots, the sporting greats, the big city pols, the movie stars, and even a few presidents,” he said in a 1973 Chicago Tribune profile.

40,000 Murphy, like his much better-known contemporary Henry Darger, was a compulsive creator who built within his home a private universe, tracing, colorizing, annotating and cutting and stapling it together from the raw material he extracted out of the real world.

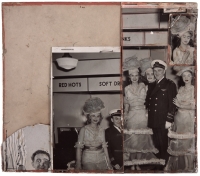

Where the loner Darger was apparently driven by the loss of family into pure fantasy, the gregarious Murphy obsessively incorporated his mother, siblings, friends and himself into nearly every piece of the environment he built. He combined their photographs hundreds of ways into collages and elaborate arrangements on his walls and ceilings, up to a dozen or more photos framed together and then aggregated by the roomfuls.

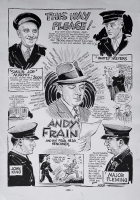

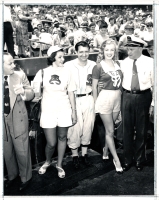

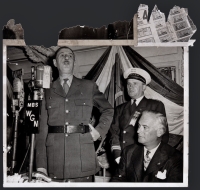

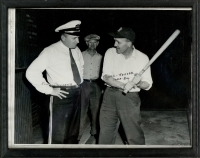

Murphy was a chief lieutenant to crowd-control czar Andy Frain, who, like Murphy, grew up in the shadow of the South Side stockyards. Frain’s ushers — Murphy was one of the first five — conducted Chicagoans through their big public events for decades. That universe encompassed any sporting, entertainment or political event that played out in Chicago: bowling at the Coliseum, horse racing at Washington Park, the Sox (and the National Colored All Star Baseball Classic) at Comiskey Park, President Truman at the Chicago Stadium, the Modern Living Exposition at Navy Pier, the Movie Star World Series at Wrigley Field, Tommy Bartlett on CBS, the Labor Rally for Roosevelt, Alderman Joe Ropa Day, Rocky Marciano fighting Jersey Joe Walcott, roller derby, wrestling, basketball, hockey — you name it. And that put Murphy in a position to get photographed with every notable he encountered and with every beautiful gal he could get his arm around.

In Two Dimensions It Shines

In this era Andy Frain’s ushers were the ultimate in decorum. (“Keep your eyes open and your big mouth shut, that’s the secret to ushering. You can’t ration courtesy,” Murphy told the Tribune.) The Democratic Machine, the unions and the first- or second-generation immigrant kids who inhabited them prevailed unchallenged. City-based factories were slamming out goods, families weren’t considered to be in crisis, and Bob Hope and Dean Martin meant class. The celebrities, Hope included, were guests in Murphy’s arena, and he displayed the easy familiarity of the shepherd as he guided them through all the glamour the city could muster at its stadiums, convention halls, sports palaces and ice rinks.

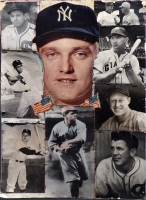

In two dimensions it shines, this lifetime of inconsequential encounters with the famous, the strong and the beautiful documented in thousands of photographs, nearly all in black and white — a combination of professionally shot portraits and publicity stills, news photos, outtakes and informal snapshots, accumulated and annotated obsessively.

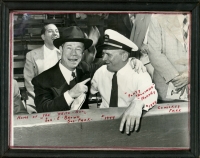

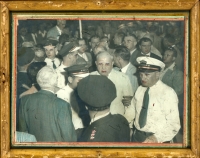

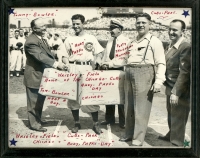

Murphy framed the pictures behind glass in prodigious quantity, marking them up with notes, decoration and other jottings. He occasionally cut out individual figures and pasted them onto other photos, and he often drew red, white and/or blue frames around the edges, whether the pictures were to be combined into collages or framed individually.

Where the images were out of focus or otherwise unclear, he completed and improved them, adding color to clothing and backgrounds and definition to faces, always trying, it seems, to rescue them from the haze of memory and photographic indistinctness. Faces often were tinted, usually in pink, and lips drawn over. Eyebrows were added when necessary. Walls were decorated with ball-point patterns that trace the wallpaper or represent entirely fictional coverings. Ties and other clothing were outlined as well.

At times he stapled or taped comic strip, newspaper and advertising clippings to the photos, or otherwise extended them, sometimes inserting an absent party into a scene: say, the late Mayor Daley pasted on another picture and extending a hand from outside the frame to congratulate Murphy’s brother Johnny on winning an award.

Murphy often combined his two great themes — family and the famous (or quasi-famous) — into a single assemblage, mixing his family with the stars in the collages and in the photos themselves, often posing his sister Dorothy or nephew Jimmie with the celebrities. Images of both family and celebrity would be copied and repeated across hundreds of image, with tributes to “dear old Ma” and “our dear boy Jimmy” appearing to outnumber the pictures even of his favorite stars, such as the skater and actress Sonja Henie.

A Campy Glamour

On most of the pictures, collaged or not, there is Murphy’s compulsive notation. A framed triptych of 9x12s shows him with a chubby Gene Autry (“Some cow-boy,” it says on the picture), a “Gebor” sister (“Some baby”) and a stockyards cow (“Bessie”). Then there’s Murphy at Wrigley Field for the 1949 Movie Star World Series, in front of the stands, his arm around a smiling young woman. “My Marilyn Monroe,” it says on the back. (He told the Tribune that she squeezed his hand when they took the picture.)

Standing in a shot with Louis Armstrong, Murphy holds a trumpet. Next to Armstrong there is this note in red (hard to see in on-screen):

The old maestro

Some boy

Hello Dollie.

(A blow-up of this picture hung in Andy Frain headquarters before the company went through an ownership change in the 1990s, along with a number of other 40,000 Murphy photos that kept him legendary there, though he had passed from working memory.)

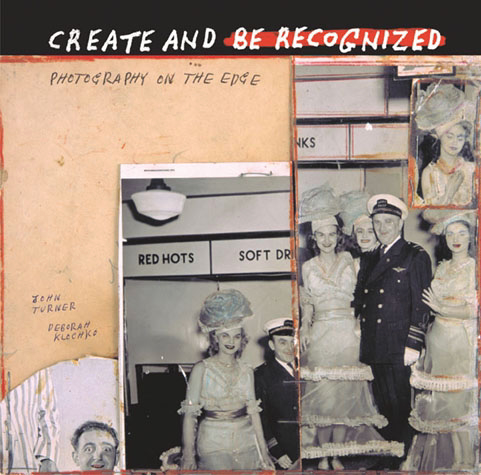

Still another photo shows Murphy and a second usher posing in front of a food concession with five skaters from an ice show (“Stadium Ice Show – Stadium – Some girls,” he has written on the photo.) In the background another skater, arms folded, looks impatient while a girl and a young woman gawk at the performers’ translucent hoop dresses, which Murphy has highlighted in red and blue ink. Eyebrows and teeth have been inked in even on an older woman who is in the background leaning against the snack stand. Plus, Murphy created a separate collage that deconstructs the main image while adding a gentleman on the left.

There is a sad, campy glamour to the decoratively costumed skaters, who turn up often in Murphy’s pictures. Like so many of the people in these photos, the women are frozen in mystery. Their talent and beauty long ago lost to obscurity, you can tell what they did for one moment, but not who they were or who they became, other than demigods in Murphy’s shrine.

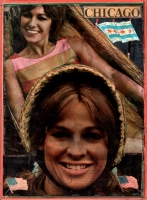

The other demigods in the shrine may not have been glamorous, but they were family. A typical piece combines 14 family images that span decades, with pasted-on American and Chicago flags and headline clippings reading “Chicago” scattered across it. “Our dear boy Jimmie… Sister Dorothy… Our mother… Our dear ma… Johnnie,” read the labels that Murphy penned in. A World War I-era soldier has his medals outlined with pen. Other faces are tinted and have their eyebrows penciled over; many of the photos have frames drawn in around them.

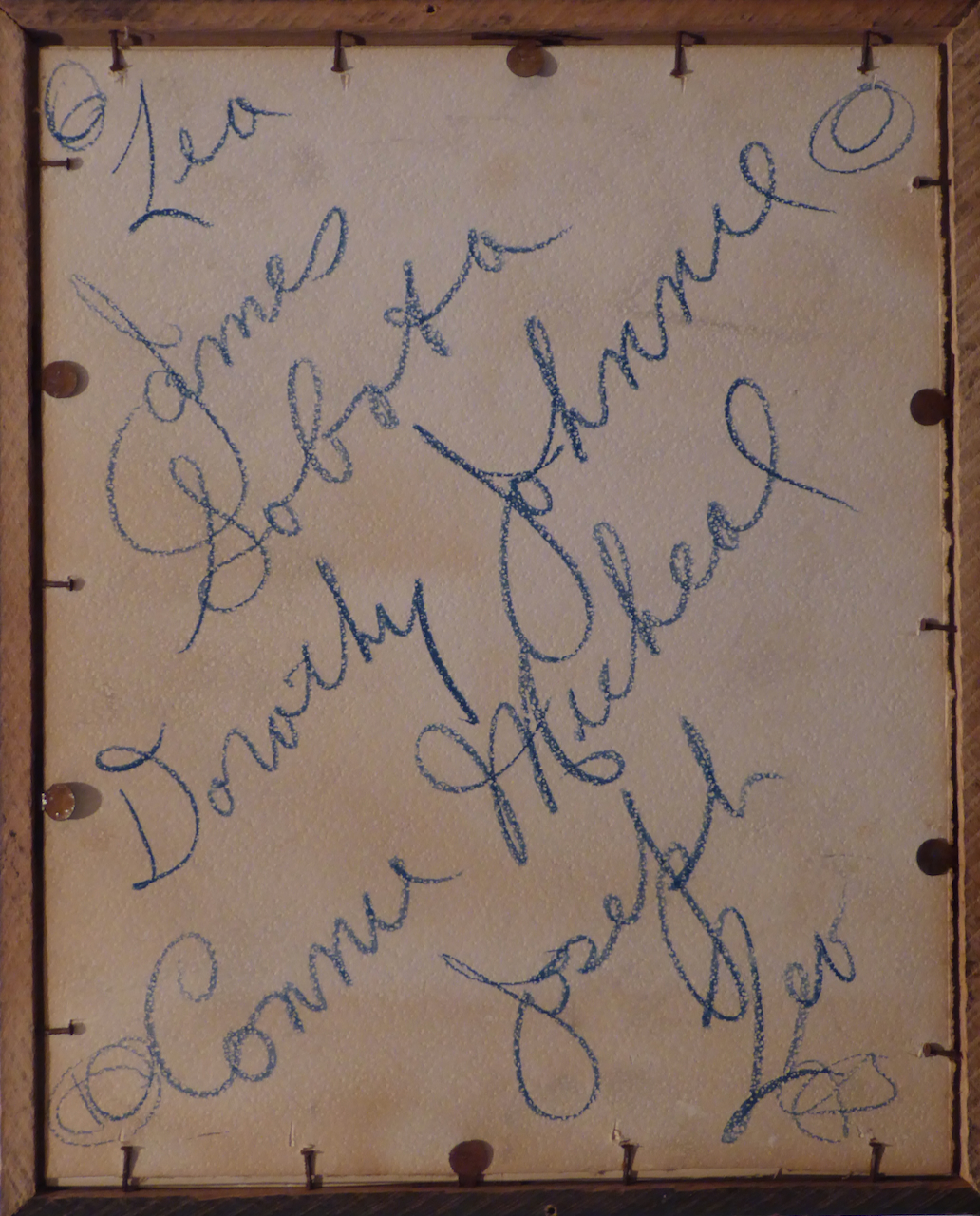

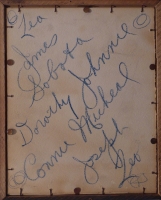

Turn the frame over and scrawled on the backing cardboard in two-inch-high characters you find perhaps Murphy’s weirdest tribute to his loved ones: “Joseph, Jimmie, Dorothy, Johnny, Leo, Dorothy, Leo, Jimmie, Connie, Michael.” These names show up over and over, scribbled compulsively on the back of hundreds of framed pictures, without regard to who is on the front. (Consider Murphy obsessively writing these names of his near and dear on the countless pieces of posterboard he used for backing.)

Murphy’s Museum

Murphy was born Joseph Cerny in 1898. He changed his last name in 1916 because, according to the Tribune, he “thought an Irish handle would make it easier to get hired in those days.” The handle kept him working through 1965, when he retired from Andy Frain. All that time he lived in the brick three-flat on 34th Street. On the back of the lot was the kind of cottage that provides inexpensive extra housing for family or longtime friends, and across the street he had a dormered five-car garage.

Murphy’s father built the house around the turn of the century, and 40,000 is said to have shared the building with his siblings, each taking an apartment.

In Murphy’s hands this stalwart home for a stalwart of Chicago’s old regime became more than a house. Along with the garage, it was a private museum to Murphy and the world passing him by. Indeed, he had cards printed up that said, simply, Murphy’s Museum.

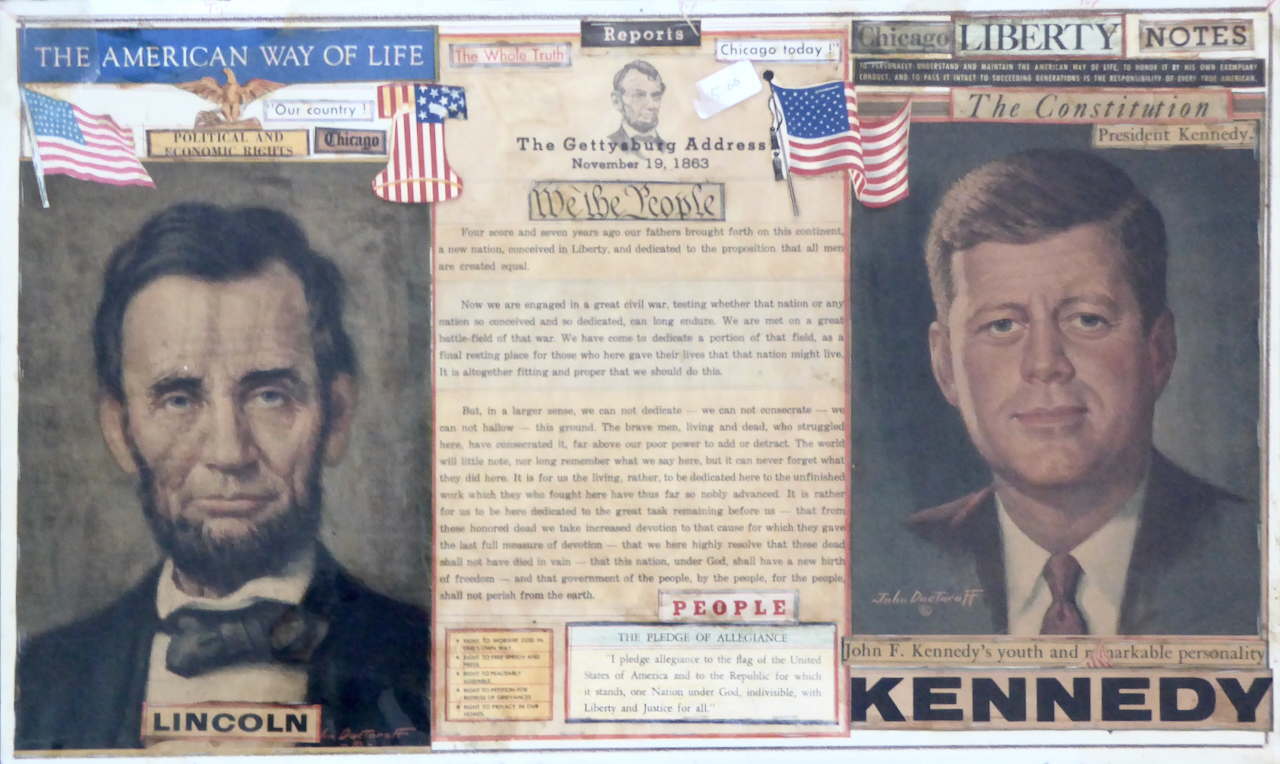

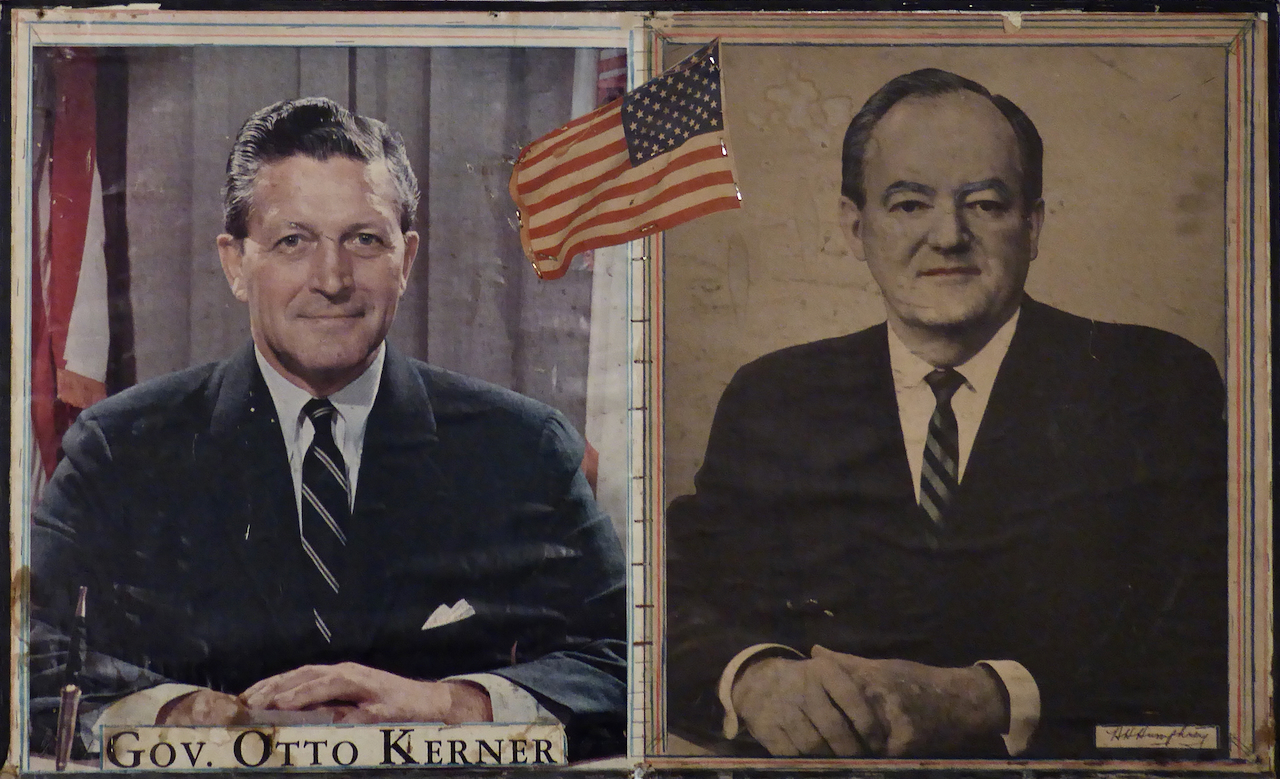

The garage was a shrine in itself. Photos were spread all over — walls, ceiling and rafters. Flag-stickered posters of President Kennedy and Mayor Daley hung from the ceiling on either size of a large model of the White House, said to be hand-made. Former Vice President Hubert Humphrey and former Ill. Gov. Otto Kerner also were memorialized in the garage, while Kennedy and Lincoln bookended the Gettysburg address and the Pledge of Allegiance.

The usual Murphy stuff also was in evidence. Pictures of models, baseball players, dearly (and too soon) departed nephew Jim Sobota, skaters and dear sister Dorothy covered the walls and ceilings, while a row of baseball pennants ran underneath Kennedy and Daley.

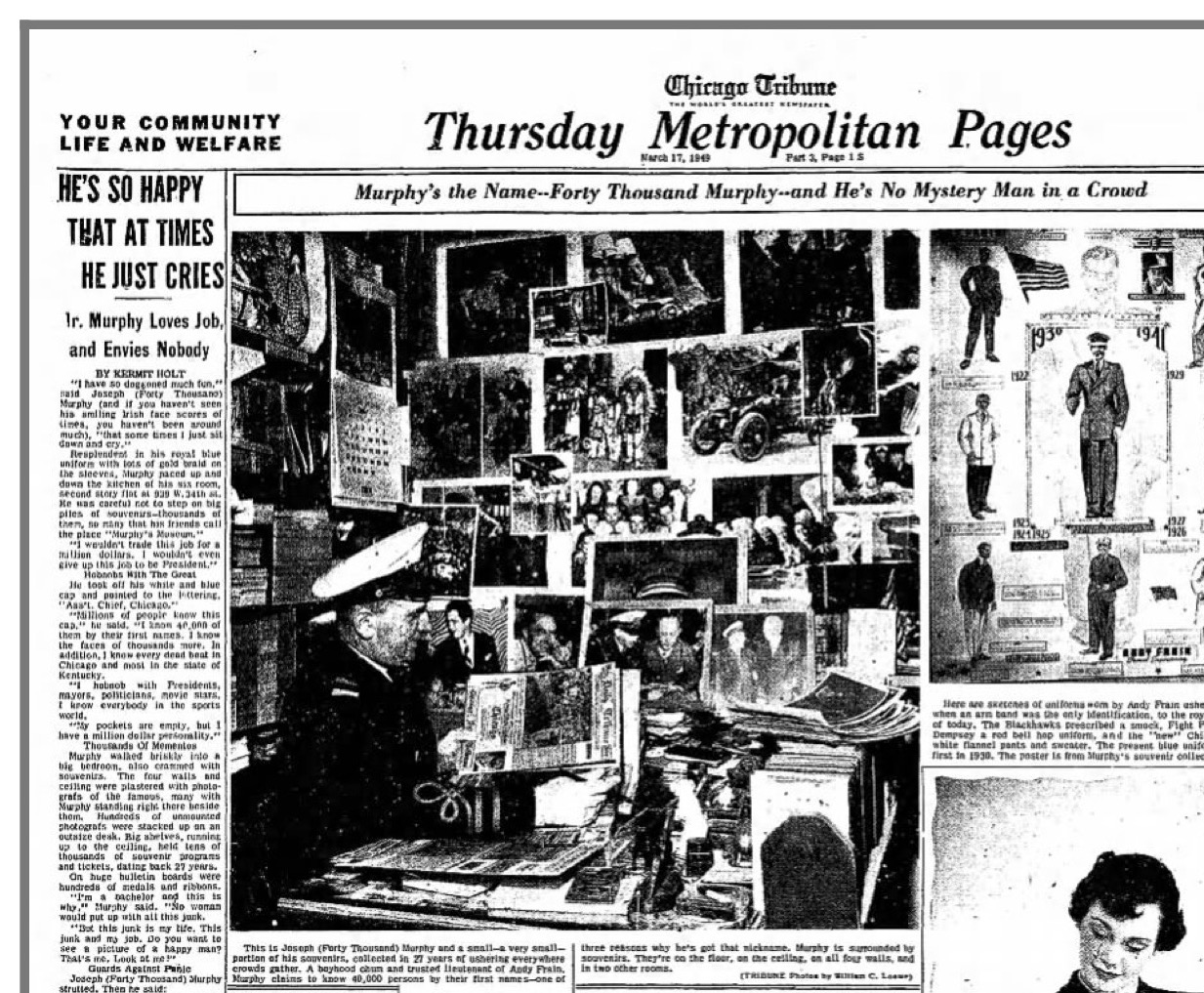

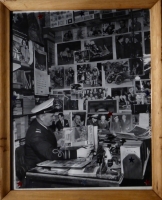

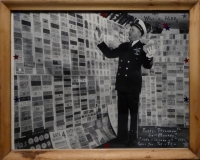

Altogether the effect, as seen in photographs taken by the Chicago Tribune in 1973, is of a walk-in collage, an impression that must have been similar in the room Murphy used as an office. Pictures were stapled to cover the ceiling, and Murphy lined the walls floor to ceiling with wooden rails set up so that framed pictures could be slid between them. Newspaper photos taken over a period of decades picture him showing off this room. (Whether visitors were delighted in the extravagance of images or astonished at its oddity is unknown.) One Tribune picture from 1949 shows Murphy and, according to the caption, “a small — a very small — portion of his souvenirs, collected in 27 years of ushering everywhere crowds gather.”

As with Henry Darger’s work, a strong erotic component comes through in much of Murphy’s creation, though opposite in tone (and not noted in the press clippings). The dark side of Darger’s erotic fantasy is all too clear in his images of violence and enslavement. Though Murphy, like Darger, never married, his eroticism seems of a piece with the joy he espoused in newspaper interviews and in his notations on the work itself. (“Some Girl” was a favorite comment or, when he showing off his collection, “What a hobby!”)

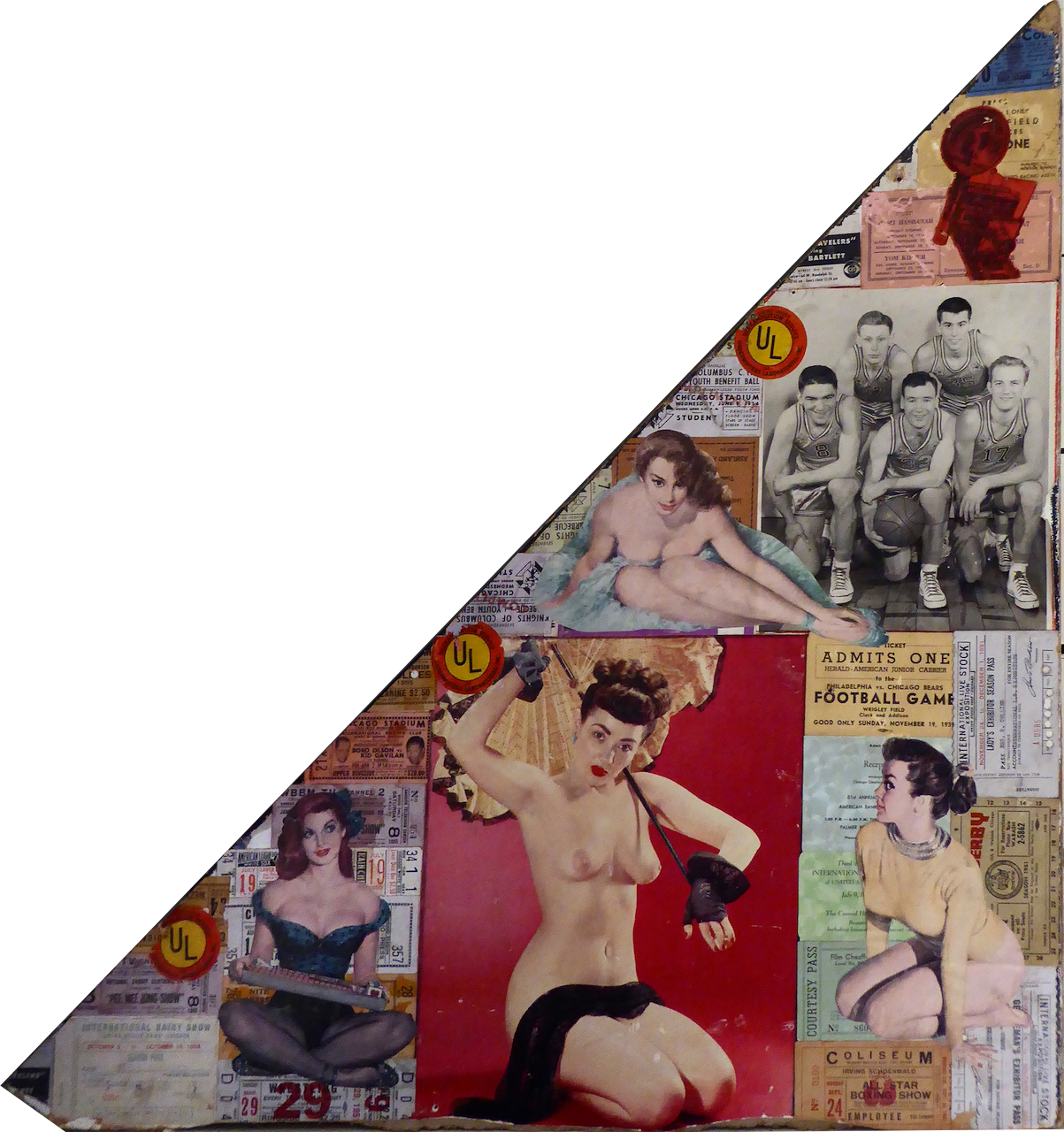

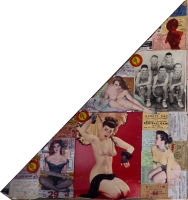

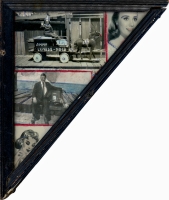

More explicitly, he built his own shrine to sexuality in a room off his attic, covering the walls with the tickets and passes that were his stock in trade, and then pasting over them a corps of calendar girls (Esquire, 1951, among others) and sex-themed cartoons. In one triangular piece from the room, Murphy surrounded a photo of himself and his beloved skater Sonja Henie with a bevy of calendar pinups.

In another, a young men’s basketball team is pasted over the event tickets along with the girls.

These sexual collages are perhaps the most unique of Murphy’s works, with colorful, inherently striking imagery. Otherwise, one piece at a time, most of his collages and enhanced photos don’t have the dramatic impact of Darger’s panels, just as Murphy’s voluminous scrapbooks presumably didn’t display the same flights of imagination that Darger put into his writings.

In Every Space A Picture

Yet Murphy’s creation, like Darger’s, was breathtaking in scope.

“It was unbelievable to go and just look. Every space there was a picture. And if there was like a refrigerator, in back of the refrigerator would have been pictures. Any place he could,” says David Nagel, who visited the house often as a child. Nagel’s grandmother Jennie was a close friend of Murphy, turning up in many of his pictures.

Where Darger’s legacy was more or less preserved, Murphy’s — his genius mostly environmental — was destroyed before it could be properly documented. Evidence of its scale and brilliance survives in hundreds of fragments, though, as well as in a stream of newspaper articles and photos and in the memories of those who saw the actual environment. That evidence points to a unique artistic vision.

“There was not an open space of wall that didn’t have a picture…. Every room you went into was pictures. There was very little furniture. But there was thousands of pictures,” Nagel says. “I don’t think he took things down once he put them up. It was one of those things where once they went up, they stayed up.”

Murphy’s contemporaries appeared to have viewed him mostly as a great, if eccentric, collector. Newspaper articles that turned up every few years generally showed amazement at his prodigious accumulation, but legitimated it by characterizing him as simply a hobbyist and an unofficial historian for the Andy Frain company.

Murphy was, in any case, a favorite of the press corps. I imagine that was in part because he could provide access to the stars, but also because he was a reliable source of quotes and commentary on the events he helped navigate, often throwaway commentary on the size of crowds.

And unlike the recluse Darger, Murphy was a well-known and apparently beloved character in his own Bridgeport neighborhood, sponsoring youth ball teams, hosting special events and even showing up in the local newspaper’s gossip column.

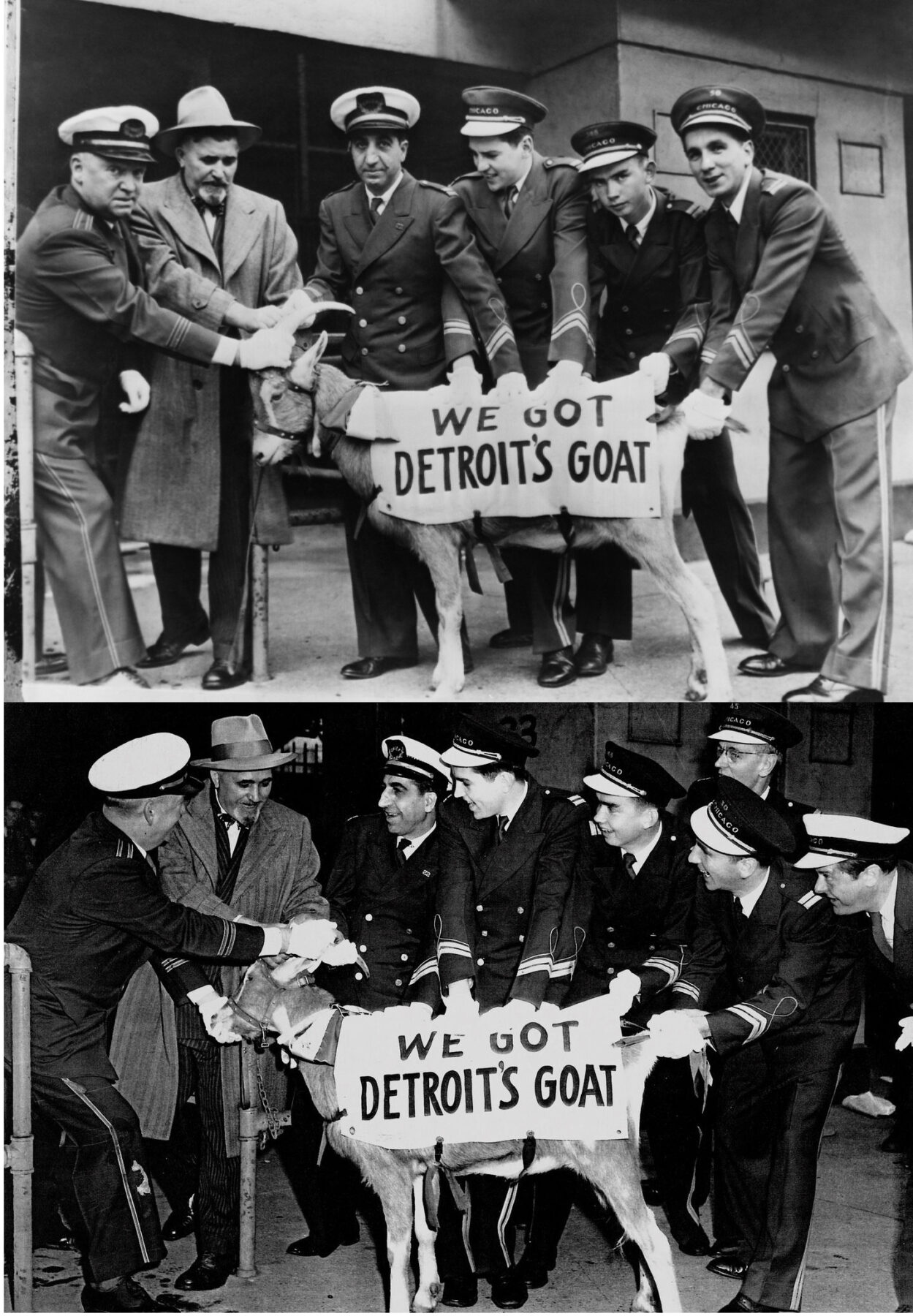

If most of his activities and encounters warranted no more historical weight than passing mentions as local color for the newspapers, Murphy was involved in one episode still being written about decades later — the famous Cubs World Series curse, or supposed curse, I should say.

The story, oft repeated in the years leading up to the Cubs’ eventual World Series victory in 2016, went like this: William Sianis, founder of the still-thriving Billy Goat Tavern, declared in a fit of pique over his goat’s ejection from the 1945 World Series against the Detroit Tigers that the Cubs would never win another one. The Cubs performance in those decades may have lent credence to the story, but not necessarily truth.

Who ejected the goat from Wrigley Field? The Andy Frain ushers, of course. And who was in the lead? 40,000 Murphy. It’s a fine yarn, but the episode was a publicity stunt, and a successful one based on the number of contemporary press mentions, none of which reported a curse. The Curse of the Billy Goat was almost certainly an apocryphal addition to this good-natured confrontation, presumably inspired over the years by the Cubs’ track record of late-season choking.

Sianis and Murphy were chums, as shown in multiple Murphy photos. Indeed, the very goat was named “Murphy” after the usher. And while one press photo shows Sianis and a crew of unsmiling Andy Frains holding the goat, another shows big smiles across the board, Murphy included. They were all in it together.

Rather than a curse, Chicago Times columnist Irv Kupcinet reported the week of the incident that Sianis simply sent a telegram to P.K. Wrigley, owner of the losing Cubs, “Who smells now?” Given the staying power of the story, it was a pretty good stunt.

A Picture Of A Happy Man

Murphy died in 1979, his passing reported in obituaries in the Chicago Sun-Times and Tribune. “’40,000’ Murphy, usher of celebrities, dies at 82,” said the Tribune, which noted that Andy Frain ushers were probably going to be needed to hold back the crowds at his funeral. (The church, St. George’s, has since been torn down.)

Murphy’s environment, recognized in the newspapers as “an unofficial Andy Frain museum,” passed with him. Before selling the building in 1991, his family had the interior pretty much stripped — a process that took a month, according to one salvager.

Bits of Murphy’s vision have turned up at antique dealers, including panels from the attic girlie room, miscellaneous photos, and huge collages of wrestlers and baseball players. The annotations evidently proved a sales liability for some of the material though; people want clean pictures, one dealer said.

Through the years, though, all that stuff never failed to impress visitors.

“His bachelor apartment reflected his consuming interest in his life as an usher,” the Sun-Times reported in its obituary. “The walls were covered with photos…. The floors and shelves were stacked with programs, buttons, badges and other souvenirs from notable public events.”

In 1949, when Murphy’s accumulation already amounted to tens of thousands of souvenirs, tickets, programs and photos, he told the Tribune: “I’m a bachelor and this is why. No woman would put up with this junk. But this junk is my life. This junk and my job. Do you want to see a picture of a happy man? That’s me. Look at me.”

Of course no one, not the reporters, nor the obit writers, nor the photographers and caption writers, nor, undoubtedly, Murphy himself, would have applied the term “art” to this lifelong effort; the house on 34th Street is an art environment only in retrospect.

But in his accumulation of intensely individual, obsessively decorated and massively displayed images and assemblages, Murphy expressed himself eloquently enough that his imagination has survived the undoing of his “Murphy Museum.” Granted, he was not exactly Henry Darger. But the world he re-created on his walls and ceilings still displayed an awesome absorption with a personal vision, a vision recognized as art only long after its creator had passed.

***

Curious about the name? The Sun-Times reported it this way:

“The 40,000 tag stuck from Mr. Murphy’s habit during Chicago’s bleak baseball days of the 1920s of estimating crowds with a laugh at ‘40,000 … empty seats.’” It was, the Tribune says, the figure he always gave when sports writers asked how many were in attendance at the ballpark. Of course, in 1949 the Tribune said in a caption that “Murphy claims to know 40,000 persons by their first names — one of three reasons why he’s got that nickname.” The third? A grateful baseball fan who left Murphy $40,000 in his will, according to the Tribune.

My 40,000 Murphy

I stumbled onto 40,000 Murphy by accident, while looking for real estate with my friend Kate circa 1990.

His house, which had remained in the family since Murphy’s death in 1979, was finally being sold. At the time it was vacant of people, but not entirely of the environment Murphy had left behind.

Although much of the material had been salvaged, the ceiling of Murphy’s office was still covered in stapled photos and the photo railings remained along the walls. The back stairs of the house were lined with pictures and, most importantly, while the attic had been stripped of the sports memorabilia that was said to have hung there, the private room near the stairs remained intact, walls and ceilings still covered with tickets and pinup girls.

At the time, this kind of space and artwork was new to me. I had no clue what it meant, just that it was weird and interesting. I was neither equipped to document it, nor bold enough to ask to remove everything left, including the wall panels from that attic room. Had I known then what I know now, I would certainly have come back with a camera and pry bar.

As it was, Kate and I asked the real estate agent showing the house if the family would sell us some of the photos. For $40-some each we got to unscrew 20 or 30 photos from the wall, which we then divided up. But we left many behind, plus everything in that attic room, and, regretfully, a basement full of decades of leftovers from parades, trade shows and the rest of Murphy’s fabulous life.

Nor did we see or even know about the five-car garage across the street.

In any case, the house itself was beyond our resources to acquire, especially since it would have needed major plumbing and electrical work.

A Hunt To Discover

That was not the end of the story, however. As I learned more about this kind of artwork and this kind of site, I began a hunt to discover where the Murphy stuff wound up. And for once, with success, though it took several years.

I bought some important material from one local antique store whose owner also told me some of the story of how it got to him, and another Bridgeport antique dealer was able to put me in touch with the picker who had salvaged the bulk of the material and, it turned out, still had it in his possession.

He was reluctant to part with it, thinking it might someday be a ticket to big bucks, but after a few years went by he determined he needed money more than some future payoff from stacks of dirty, apartment-filling photos and posters. So we made a deal for a modest sum, and I became the custodian of several hundred bits and pieces of Murphy’s fabulous life.

In the meantime I picked up odds and ends at other antique stores around the Chicago area and bought a group of photos that had been acquired by a local folk art collector.

In fact, it appears that a good deal of Murphy’s environment had been stripped out years before I saw the house, perhaps from the garage rather than the house. A 1982 article from a Lemont, Illinois, newspaper mentions an antique store that was said to be displaying more than 1,000 Murphy photos.

For me, the existence of this other Murphy material is a cause for excitement, not disappointment. It means there is more that might turn up some day.

A Small Sample of 40,000 Murphy’s Artwork

***

A Joe “40,000” Murphy Update

For the archivally minded, a version of this 40,000 Murphy article was the first major post I made to my interestingideas Web site, in 1994. If you want to see more or less what it looked like then, click here.