Unsealed: Bottle Cap Art | The Woolseys | The Patent Drawings | How To | The Race Question | The Blockbuster

The Galleries: Masterworks | Troops | Signed | Flashers | Other Shapes | Mine | Bottle Cap Inn | Two Monuments

It may seem odd that discarded caps from beer and soda containers inspired a quintessentially 20th century folk craft. But crown caps, patented in 1892, were new to the century, and as used bottle caps accumulated, creative individuals started to think about what to do with them. Millions were pounded and strung into small figures, baskets, buildings, animals, chains, miniature furniture, and full-blown sculptures. The result: Bottle-cap art.

It was a scavenger craft of humble origin. Its rough edges and make-do aspirations have made it a sort of poor cousin to tramp art, quilting and other respectably collectable folk objects.

Why is this craft quintessentially 20th century? Because it is strictly Machine Age. Their Wikipedia entry calls crown caps “the first highly successful disposable product.” To make art they were typically strung on repurposed clothes hangers or other factory-made wire. And the most common bottle-cap creations are of a piece with other crafts of their time, like sock monkeys — the repurposed detritus of industrial production and surplus.

Anonymous bottle-cap figures abundantly populated thrift-store shelves in the early 1980s before making their way to the world of antiques and Americana. Now they might on occasion show up in eccentric corners of design-magazine photo spreads, but mostly they haunt the lower reaches of eBay, usually fetching the same $20 to $40 that they did 10 and 20 years ago.

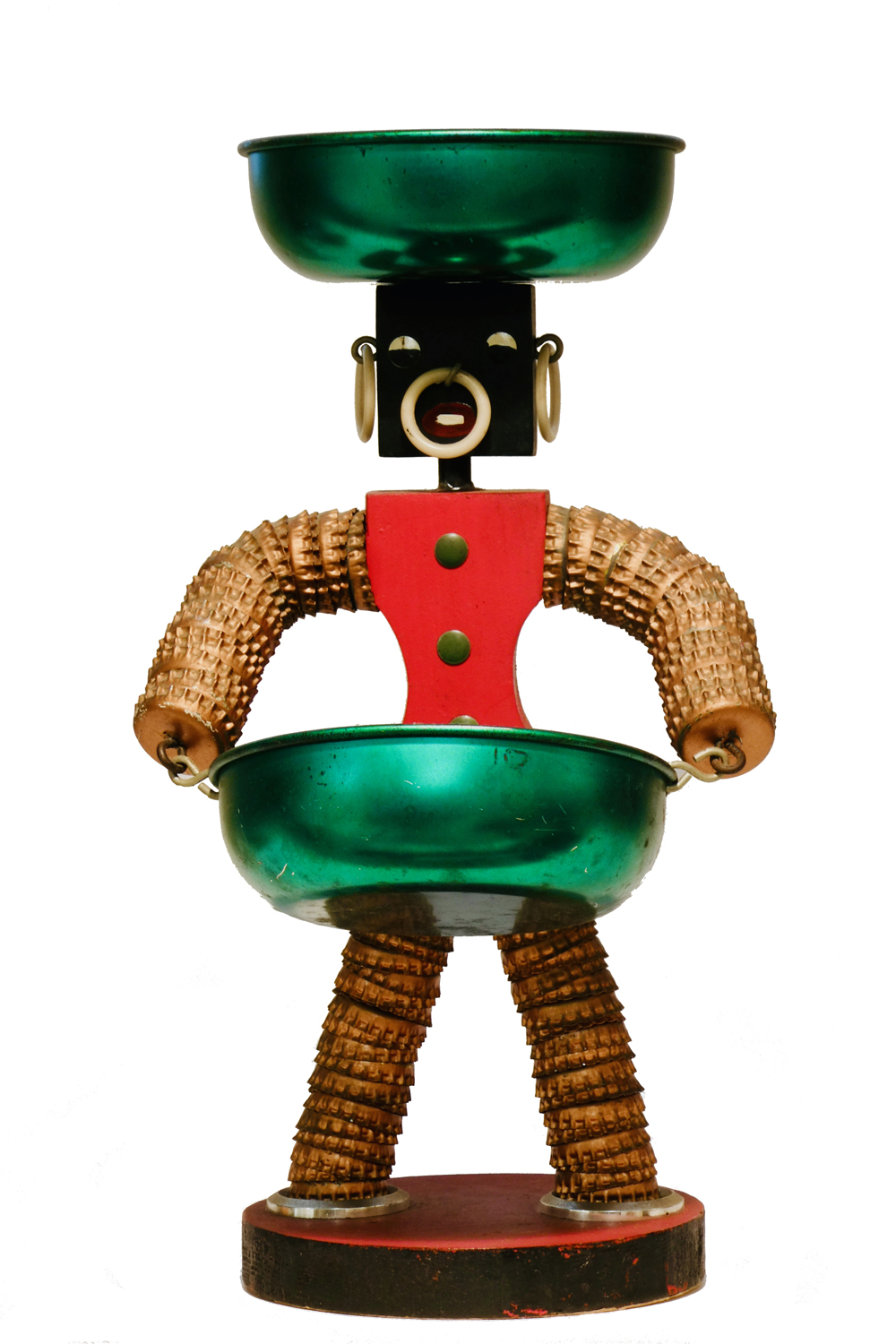

These figures are about a foot high, their wood-block bodies often decorated with a grid of incised lines, and sometimes glitter. Alternatively, and almost as often, their wooden bodies are tapered to an hourglass figure and otherwise unadorned. Their serrated bottle-cap limbs hold a candy dish or ashtray; another tray is usually nailed to the head. The eyes are thumb-tacks, the ears wire or plastic hoops. Often the mouth is missing and a nose ring completes the face.

Aesthetically, one of their legs is planted in the mass-production world of tchotchkes and kitsch objects, but the other is in the folk-art universe of hand-built, one-of-a-kind works by untrained, usually unknown, creators. While high-culture urges are absent and pretension would be laughable, these figures display a certain charm in their haphazard expressiveness.

They are almost like 3-D projections of cartoon characters in their silliness, though like some cartoons some bottle-cap pieces have an edge — more like an R. Crumb character than Mickey Mouse. Case in point: figures outfitted with a beer- or soda-can body that reveals genitalia when lifted.

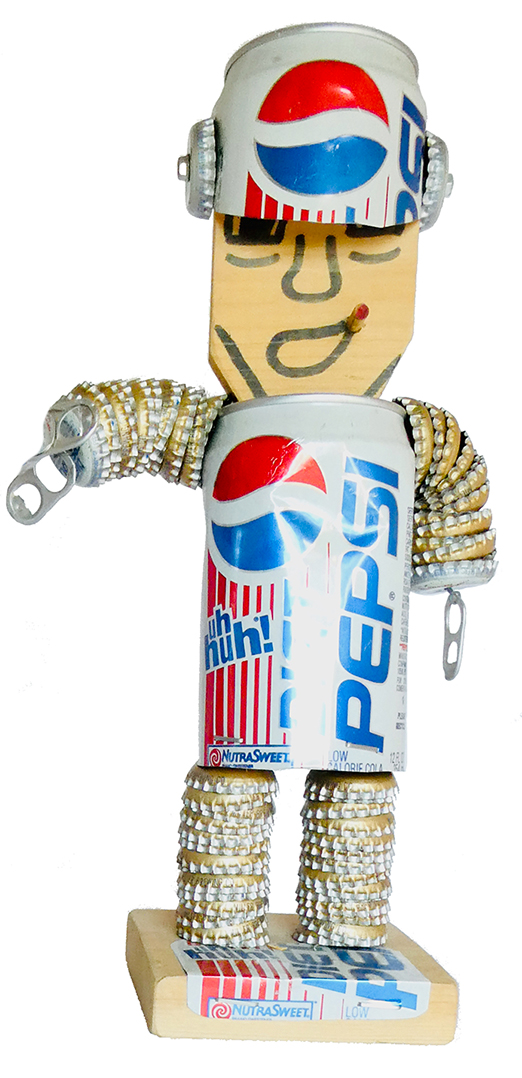

These flasher figures are a common bottle-cap genre — gag items probably destined for bars or similar venues. They also shows signs of recent production (certainly into the 1990s) vs. the 1960s-70s vintage more typical of other figures.

The trial-and-error process of adapting a basically conventional design to a builder’s own purposes allows a personal touch to squeeze through the prosaic materials and often-uncertain craftsmanship: in the choice of materials and colors, in how a face is suggested, in how a figure is positioned and accessorized. Although most of those figures are based on a handful of standard patterns, some figures reflect a more idiosyncratic exploration of the form. Thus one artist pasted a photo of Lucille Ball’s face onto a realistically shaped wooden head and gave her a bass fiddle to play. Another fashioned bottle caps into a strand of sausages (or perhaps it is a jump rope) for a thickly painted figure to hold. Figures occasionally turn up decked out in clothes, outfitted with a carved face, hands or feet, or holding a variety of oddball objects (including a pregnant figure carrying a sign reading, “I was brainwashed”).

Since departures from the norm most richly reveal the maker’s hand, the most primitive figures — the ones with the free-est-form bodies, the wildest mixtures of bottle-cap colors and the most loosely suggested faces — can be especially intriguing. This sets bottle-cap work apart from, say, tramp art, where intricacy and high levels of craftsmanship typically define quality.

Still, there is something of tramp art’s accumulative spirit in the striking textures of massed and strung bottle caps, especially in baskets, which reflect a similar mix of decorative and utilitarian impulses. These abstractions of twisting bottle-cap strands, which range from small candle holders to umbrella stands, are a good deal rarer than the figures and tend to display a more ambitious play of form and a greater design variation.

They also appear to be older than the figures, most of which can be reasonably dated to the 20 or so years centered on the 1960s. The patina of the baskets and the designs of the caps would seem to put them further back in the century, making them a kind of funky successor to tramp art. Dating bottle-cap art is necessarily imprecise, though. Shrouded in anonymity, it has been the subject of almost no published research.

Occasional figures have identifiable origins. One, of the tapered body variety, is signed “Scouts La Grange Park” and dated 1961. An Earl Clapper, who lived in Chicago’s South Side Brighton Park neighborhood, put his return-address sticker on a figure of similar design sometime before 1963, when ZIP codes were introduced. The Chicago-area locations are no fluke, since the Midwest seems to be the most common source for figures.

A similar address sticker appears on a figure that allows its attribution to a creator known as the Oshkosh Master of the Carved Nose and Mouth, who produced quite a few similar nicely crafted pieces sometime after 1963 (like the one illustrated on the right atop this page).

We can assume that George Kasperan Jr. (1949-2016) of Vernon, Connecticut, was producing figures in the 1960s since he was issued a patent for his “Snack Server” in 1970. More details about the patent here.

A ’60s-or-later origin is apparent for a number of other pieces because the bottle caps are imprinted with zip codes or lined with plastic rather than cork, both early-60s innovations. Many of the flasher figures are fairly recent and likely to be commercial. One, for example, is stamped with the post office box of a Can Man Co. in St. Louis, while a male and female pair found in Florida are new enough to sport Diet Pepsi’s 1990s “Uh Huh” slogan on their bodies.

Stickers from the Junior Achievement program show up periodically on bottle-cap material. In the 1950s and ’60s, trios of adult JA advisers would use catalogs of ideas compiled by the organization to find things for their groups to make and sell, according to JA veterans. The point was to teach young people about business by assisting them in operating one of their own. The products that resulted, which included lamps, cutting boards, coat hangers and other mostly household items, as well as bottle-cap figures, were marketed to family members, door to door, and at fairs and open houses, according to John Dickinson, a former Junior Achievement executive who said bottle-cap figures and animals were made by JA groups all over the country in the ’50s, the ’60s and into the ’70s.

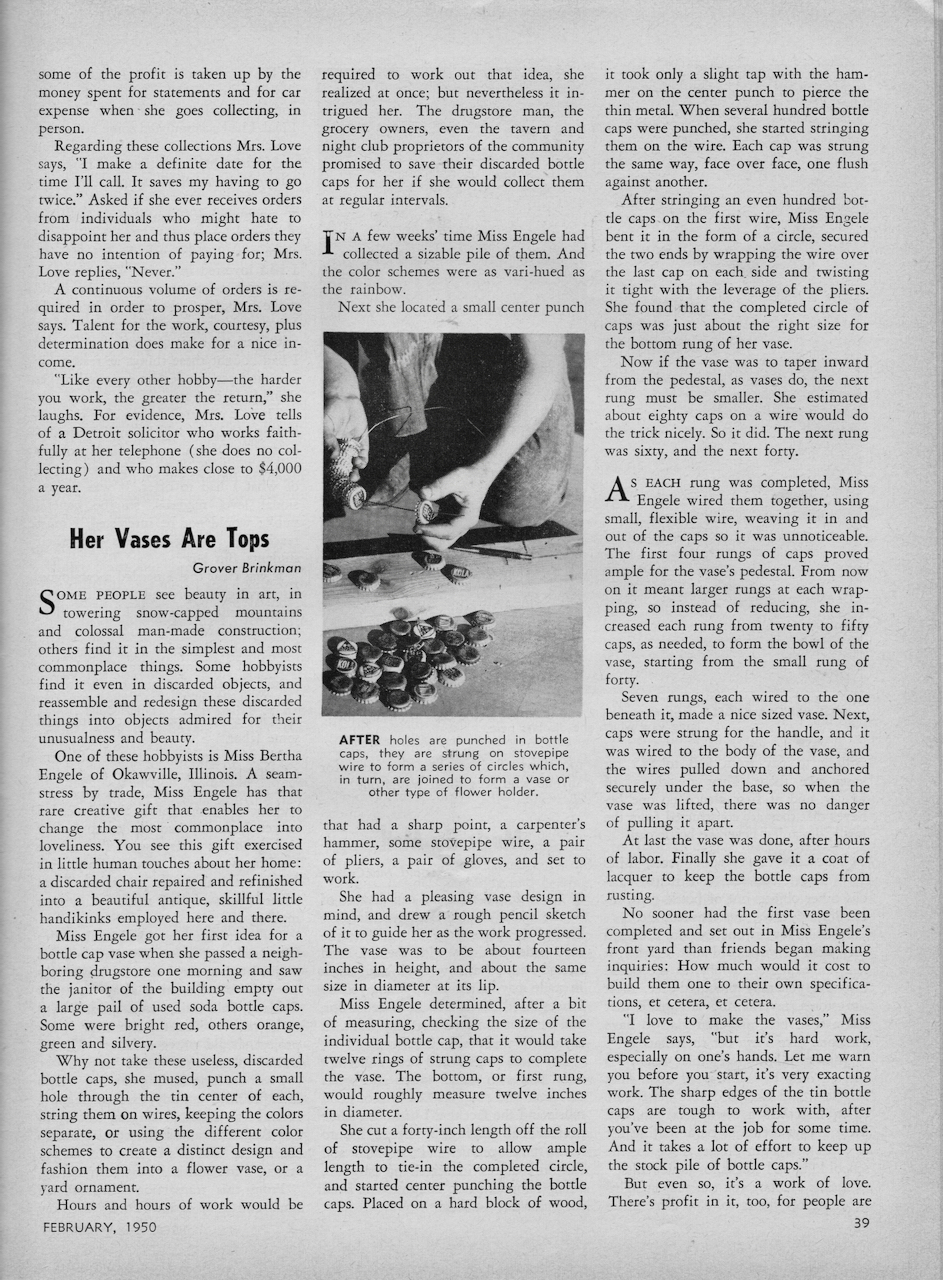

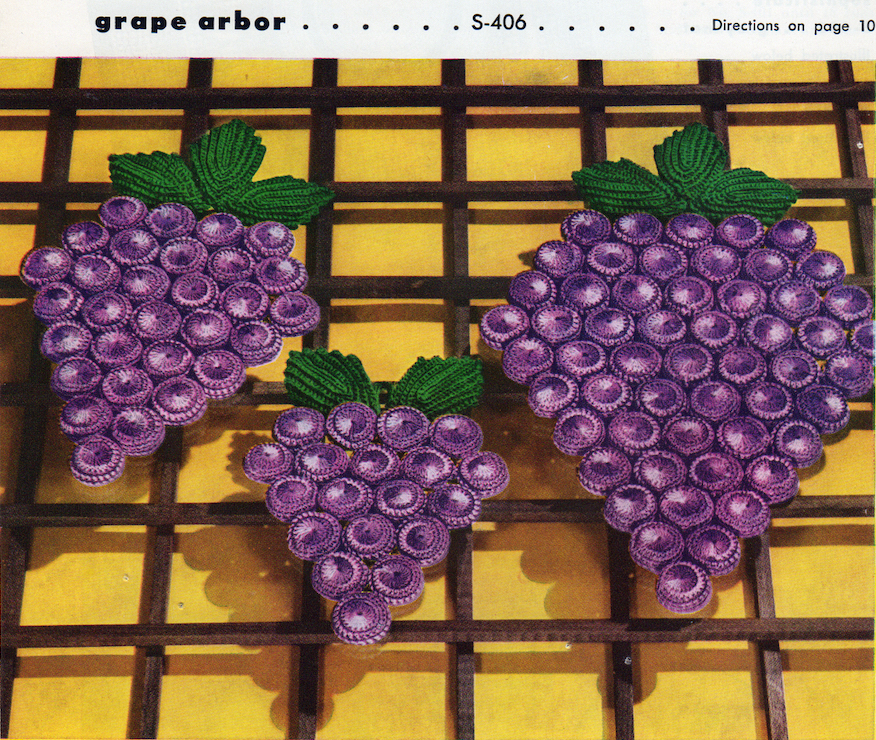

Where Junior Achievement, or other builders, got the idea to make the figures is unknown, however. Instructions reportedly can be found in magazine articles or craft books, but an extensive search of books, magazines, and related publications from the late ’40s through the mid-60s turned up only a handful of references to bottle-cap crafts. One mentioned a Wisconsin boy who sold small toy models made from bottle caps and fruit-crate wood to tourists for $1.50 to $3. A number of articles articles refer to crocheted bottle-cap trivets and placemats.

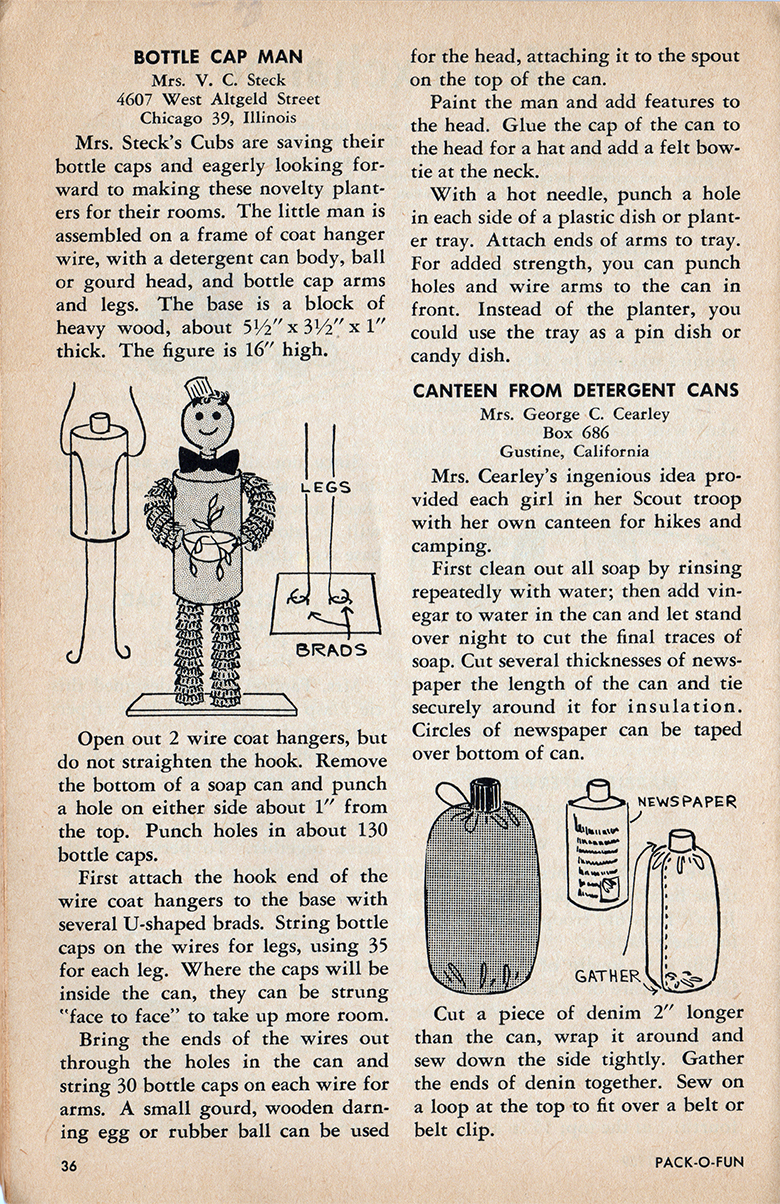

The most relevant example appeared in a summer 1959 edition of Pack-O-Fun, “the only scrap craft magazine.” WIth its body made from a can rather than wood it’s not a classic example, but it does reference stringing caps together to make a figure. Whatever other written sources existed, they apparently were not in common circulation, however. More on the Pack-O-Fun article here.

(Almost as obscure as the genesis of the baskets and figures is the exact nature of the figures’ imagery. The problem, for some, is a color scheme that often runs to black, in tandem with nose rings and other “primitive” features. See more on the topic here.)

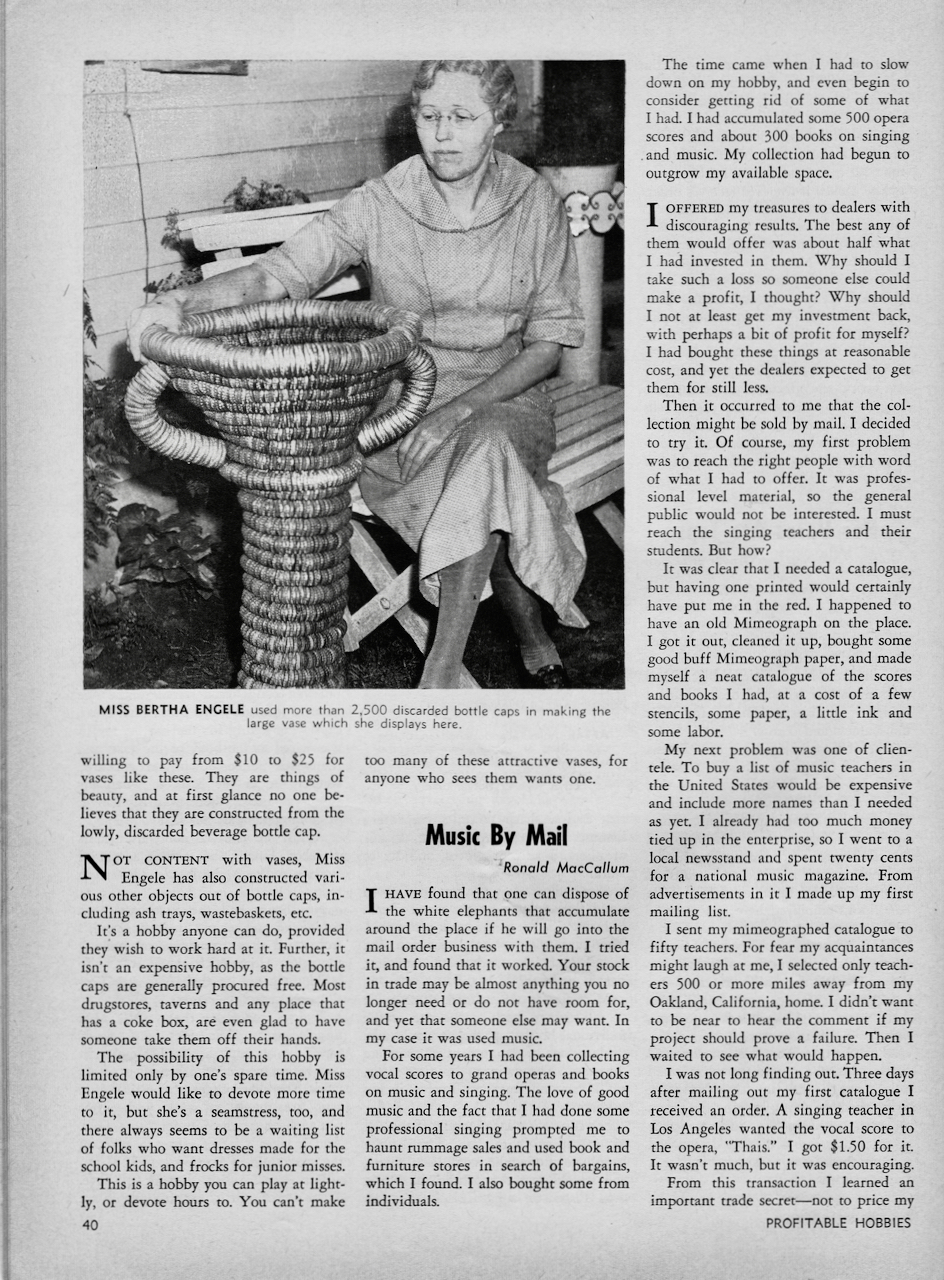

A rare case of an early bottle-cap creator documented in her lifetime is provided by a 1950 article in Profitable Hobbies magazine about Bertha Engele (1891-1953), a seamstress from Downstate Illinois who discovered a sideline when she saw a drugstore janitor dumping a pail of brightly colored old bottle caps. She had the idea of stringing them together to make vases, baskets and other objects. The magazine described her technique in detail, and included a picture of Engele with an elaborate vase that appears to be about three feet tall and that consumed more than 2,500 caps. That picture had previously appeared in a 1942 issue of the Gibson City (Illinois) Courier, dating her bottle-cap activities at least to the early 1940s.

Engele was also an inventor. In 1937 she was issued a patent for an electric Marcel machine, offering an improved technology for curling hair. It’s also worth noting that her social doings were regularly reported over the years in her local newspaper, The Nashville (Illinois) Journal.

Engele sold her bottle-cap work for $10 to $25, according to Profitable Hobbies, which noted, “They are things of beauty, and at first glance no one believes that they are constructed from the lowly, discarded beverage bottle cap.” As for Engele, she is quoted as saying, “It’s hard work, especially on one’s hands…. And it takes a lot of effort to keep up the stockpile of bottle caps.”

The obsessiveness that facilitates that effort can be seen modestly in the common bowl-bearing figures, with their 80 or 100 caps; more clearly in bottle-cap chains that can stretch 50 feet or more; and even more impressively in Miami’s Bottle Cap Inn.

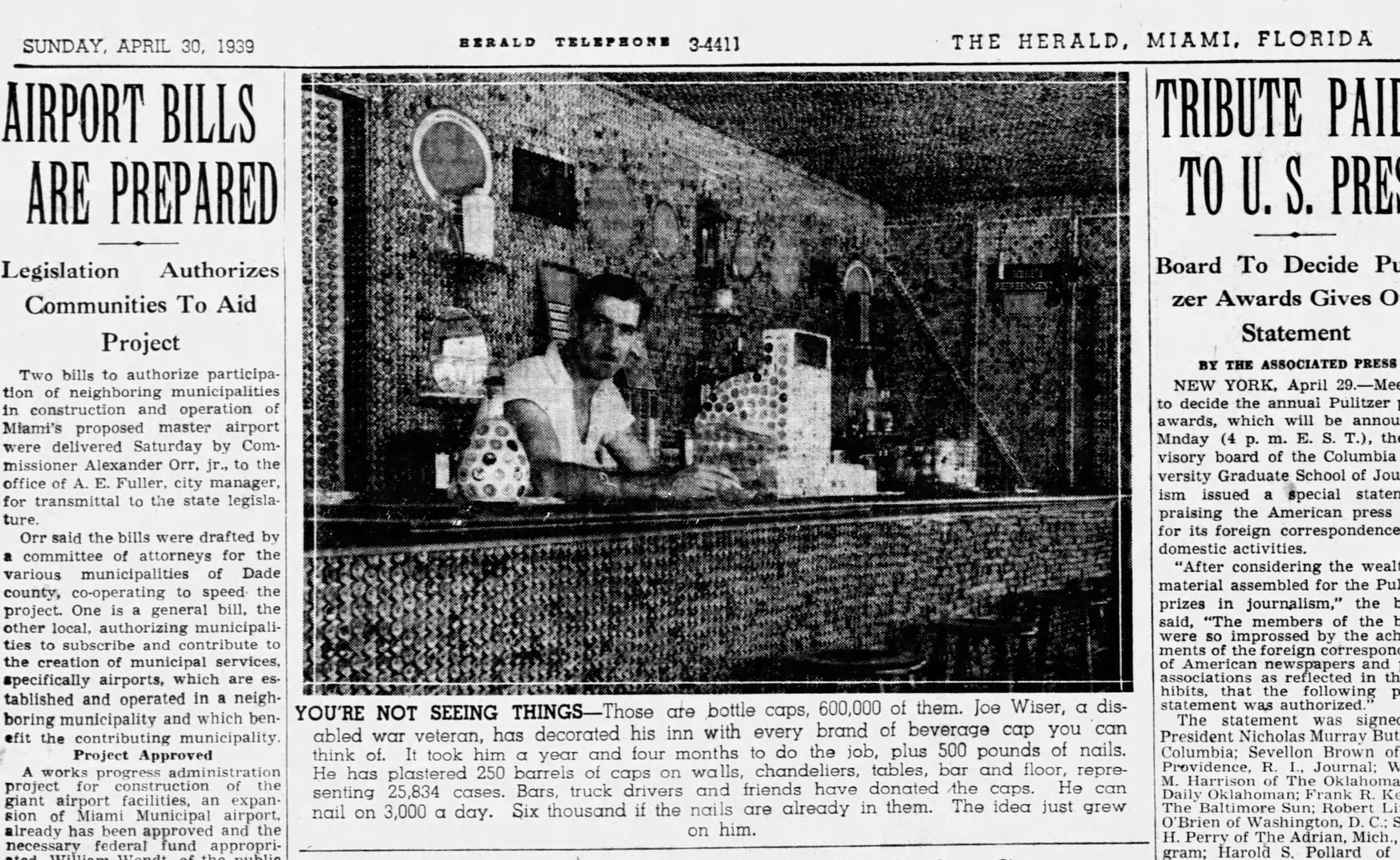

Joe Wiser (1895-1964), a carpenter and disabled veteran, collected some 600,000 bottle caps in the 1930s, according to the catalog for the 1987 art exhibit, A Separate Reality: Florida Eccentrics. He washed and varnished them, nailed them to almost everything in his bar and restaurant, and gave birth to the Bottle Cap Inn, which lasted in north Miami into the 1990s. Wiser’s art environment was documented in contemporary postcards, 1940s press photos, and in Ripley’s Believe It Or Not. You can see examples here.

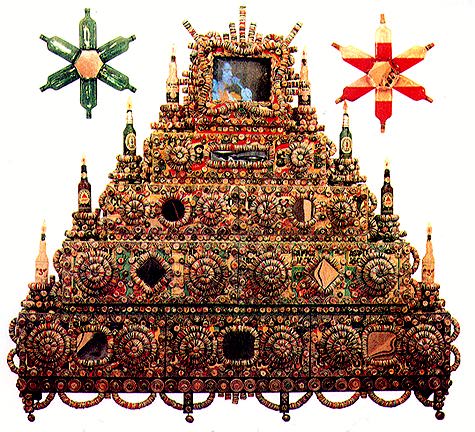

The work of Iowa farmworkers Clarence and Grace Woolsey, like Wiser’s and Engele’s, made it into their local newspapers. And after their death it roiled the art and antiques world, both in its prodigiousness and in the stunning price appreciation following its 1993 rediscovery. The Woolseys produced more than 200 individual pieces of art from bottle caps, some of it quite large in scale. Read about the Woolseys here.

You don’t have to be obscure or folkish to show traces of obsession in this genre. Some of the self-taught Mr. Imagination’s (1948-2012) small bottle-cap pieces are about the size of the common anonymous figures, but they are more personal and elaborate. He is best known for his larger works, including bottle-cap mirrors, totems and full-size thrones. His massive use of caps — strung, nailed or layered — exploits their structural properties, while his vision earned him nationwide recognition, commissions, and museum exhibits. Mr. Imagination was from the Chicago area but later in life moved to Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and then Atlanta.

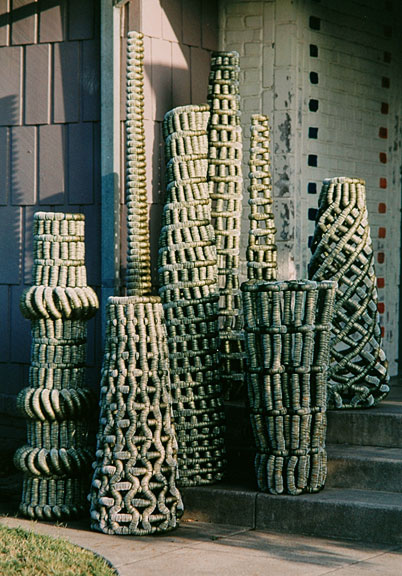

Some constructions by Clare Graham of Los Angeles match Mr. I’s in scale but are more minimalist in form. His baskets show how suitable a medium caps can be for abstract sculpture. Like Mr. I’s large pieces, his baskets and buildings often represent impressive engineering achievements as they explore the caps’ formal properties. Graham got interested in bottle caps after finding an old basket at the Rose Bowl swap meet. He started building chains, he says, and then, following the character of the material (the multiplier effect of masses of caps cupped together) evolved into building more complex forms.

“It gives a great deal of visual and structural integrity when it’s massed. It’s really an incredible detailed, dense surface, sort of jewel-like.” Graham has worked with pull tabs (he’s used 7.5 million, he says) and dominoes, and he has made Towers of Babel with Scrabble tiles and other game pieces. (See more here.)

Brooklyn-based Rick Ladd — like Graham a trained artist — encrusts furniture and home furnishings with bottle caps for an effect that owes less to bottle-cap figures than to tramp art, which he collects. He says he made his first bottle- cap piece as a substitute when he couldn’t find a tramp-art dresser to suit him. He had seen some bottle-cap chains at the time, he says, but not too much else in the genre.

“I started playing with the form, and from there it grew out. It’s exuberant and overdone,” he says, adding that the process of pounding holes in the thousands of caps he uses “is really meditative.”

I can testify to the meditativeness of pounding holes in caps, having pounded hundreds myself to make a bunch of figures in the 1990s.

In the marketplace you can substitute money for meditation. The Woolsey work was hot enough that counterfeits appeared within months of its rediscovery, reportedly made with leftover caps from the estate.

Appreciation has not been so extreme for the anonymous work. Plainer baskets occasionally dip below $100, but $200 and up is more common. Bottle-cap chains can be found for as little as $50 in short lengths, but $150 to $500 or more is typical.

As for the bowl-holding figures, from a dollar or two just a few decades ago even the most common ones usually fetch $25 and up, whether sold as folk art or ’50s kitsch. The older a piece is and the more it departs from the norm, the more it is likely to be worth a premium, of course. Prices of $150, $200 or more are not unheard-of for especially odd pieces, with very tall figures, carved faces, exuberant decoration, animal figures or figures holding something other than bowls among the pricier work.

Whatever the dollar value, the notion of bunches of ordinary people toiling away anonymously to produce these absurdist little figures has its appeal, even if it remains a mystery just who was the original artist who decided it made such good sense to string bottle caps on coat hangers, stick them into blocks of wood, put nose rings and earrings on them, and have them hold candy dishes or ashtrays. They will always be faintly ridiculous, but as objets d’folk art that just adds to their appeal.

Elsewhere online, you can still visit a slice of Bottle Cap Art Heaven: Philip Lamb long ago created a page devoted to his collection. It is beautiful, and he has informative notes on every piece.

This is a revision of my original piece, published in conjunction with Intuit’s 1994 exhibit Crowning Achievements: The Crimped & Cutting Edge in Bottle-Cap Sculpture.

Unsealed: Bottle Cap Art | The Woolseys | The Patent Drawings | The Race Question| The Blockbuster

The Galleries: Masterworks | Troops | Signed | Flashers | Other Shapes | Mine | Bottle Cap Inn | Two Monuments