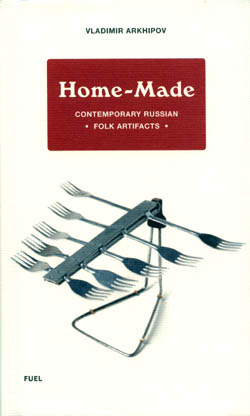

Home-Made: Contemporary Russian Folk Artifacts, by Vladimir Arkhipov, Fuel Publishing, 304 pages, 180 color pictures, 2006. ISBN 0-9550061-3-9

Folk Archive: Contemporary Popular Art from the UK, by Jeremy Deller and Alan Kane, Book Works, 158 pages, 2005. ISBN 1 870699-81-5

Two recent books from abroad attempt to document the spontaneous art making of ordinary people, one broadly and one eccentrically.

Two recent books from abroad attempt to document the spontaneous art making of ordinary people, one broadly and one eccentrically.

Folk Archives, from Britain, covers a wide range of vernacular expression, from protest posters to shop signs. Home Made, also published in Britain, takes a certain kind of ingenuity as its subject, specifically creative responses to the acute scarcity of consumer goods in the Soviet Union and its aftermath.

Folk Archives collects the more obviously artistic material, including a number of conventional (if sometimes clearly self-taught) paintings and sculpture, where the artifacts of Home-Made are far more prosaic – flashlights, screwdrivers and floor lamps, among other things.

While the bodies of work in some instances feel familiar (hand-painted shop signs from Britain, a cloth toy animal from the Soviet Union), in others they seem rather alien. The British protest art doesn’t track to any living tradition in the U.S., nor do the makeshift knives and forks from Russia. As hand-crafted utilitarian objects, though, the Russian pieces resonate with traditional folk craft, and like those objects they occasionally attain aesthetic distinction. Home Made makes a strong case that even the most mundane of these objects convey a message about the society and the people who made them.

The primary folk tradition resonating in the Soviet material is a strain of getting by with what you’ve got. “It was necessary to make a record box as there were records but no box,” explained one practical-minded creator.

For author Vladimir Arkhipov, who has collected more than a thousand of these makeshift items, this material helps explain the stagnation for which Soviet society was notorious: “Each person who can make something with his hands prefers to make something small and concrete rather than uniting with others to change their lives. Everyone still struggles with their own problems alone.”

The finest examples of these small things, whatever their sociological implications, constitute a reminder that expressive is not the only important result of creativity as expressiveness. Elegance can be an equal source of delight. Radio and TV aerials, one made from forks, one from baskets and some from stray bits of wire, are abstract sculptural figures worth of aesthetic contemplation, if only by coincidence. As Arkhipov points out, “The most interesting visual traces left by creation are those that have not been subject to conscious aesthetic assessment by their creators.”

Along with these visual traces, the creators leave behind evidence of a sort of petty heroism, as well as an ingenuity that still has the ability to intrigue.

The creations documented in Folk Archives tend to be more expressive in intent, and demonstrate a wide range of meaning indeed. The documentation ranges over baked goods, customized cars, customized underwear, tattoos and Princess Diana shrines, among other things. The profusion of decoration and expression hardly allows for a unifying theme similar to the matter-of-factness of the Home-Made material. But a clear message does come through the eclecticism, and that’s the anything-goes spirit that is nowhere more visible than in untutored creation.

Among the most interesting examples in the book is a building from Cardiff whose windows are all covered with protest-sign handwriting reminiscent of Missouri’s Jesse Howard. Protest materials make up a whole genre in this collection as do both prison art and the decorative effusions of public festivals. All in all, it provides a taste of the British popular culture landscape that you are unlikely ever to see unless you live there — and go out of your way to notice.

A version of this review originally appeared in Outsider magazine, published by the Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art.

I declare myself,a outsider of art.

Full of Ideas and projects,and soo will be able to carry them out.

In my new studio on the 3rd floor of our HISTORICAL HOME in NJ.

Philip Freneau was a Revolutionary war Poet and lived here allmost 200 yrs ago.For Christmas I gave my Husband his own site,

philipfreneau.com you can learn all about this Rascal,as Jefferson called him often. I am working on dolls with tattoos, well orignial art of rock starrs,and there tags….also many animal art peices in clay!

This is a great site and full of inspiration! thanks,linda

outsider of art,I am trying to submitt my site through my web site host and I dont see it come up here? What do I need to do diffrently to acheive that engine searchability here???

happy creating!